Back Gebeurtenisse wat tot die Eerste Wêreldoorlog gelei het Afrikaans Der Weg in den Ersten Weltkrieg ALS أسباب الحرب العالمية الأولى Arabic Прычыны Першай сусветнай вайны Byelorussian Причини за Първата световна война Bulgarian প্রথম বিশ্বযুদ্ধের কারণ Bengali/Bangla Příčiny první světové války Czech Årsager til 1. verdenskrig Danish Esimese maailmasõja põhjused Estonian علل جنگ جهانی اول Persian

| Events leading to World War I |

|---|

|

|

The identification of the causes of World War I remains a debated issue. World War I began in the Balkans on July 28, 1914, and hostilities ended on November 11, 1918, leaving 17 million dead and 25 million wounded. Moreover, the Russian Civil War can in many ways be considered a continuation of World War I, as can various other conflicts in the direct aftermath of 1918.

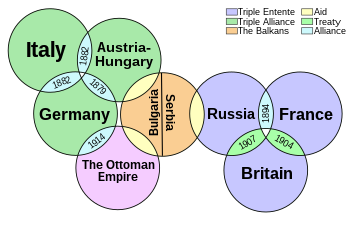

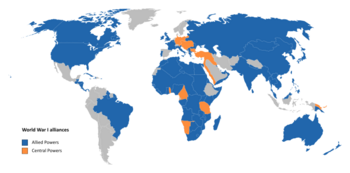

Scholars looking at the long term seek to explain why two rival sets of powers (the Allied Powers and the Central Powers) came into the war in 1914. They look at such factors as political, territorial and economic competition; militarism, a complex web of alliances and alignments; imperialism, the growth of nationalism; and the power vacuum created by the decline of the Ottoman Empire. Other important long-term or structural factors that are often studied include unresolved territorial disputes, the perceived breakdown of the European balance of power,[1][2] convoluted and fragmented governance, arms races and security dilemmas,[3][4] a cult of the offensive,[1][5][4] and military planning.[6]

Scholars seeking short-term analysis focus on the summer of 1914 and ask whether the conflict could have been stopped, or instead whether deeper causes made it inevitable. Among the immediate causes were the decisions made by statesmen and generals during the July Crisis, which was triggered by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria by the Bosnian Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip, who had been supported by a nationalist organization in Serbia.[7] The crisis escalated as the conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia was joined by their allies Russia, Germany, France, and ultimately Belgium and the United Kingdom. Other factors that came into play during the diplomatic crisis leading up to the war included misperceptions of intent (such as the German belief that Britain would remain neutral), the fatalistic belief that war was inevitable, and the speed with which the crisis escalated, partly due to delays and misunderstandings in diplomatic communications.

The war followed a series of diplomatic clashes among the strongest great powers in the world (Italy, France, Germany, Turkey, United Kingdom, Austria-Hungary and Russia) over European and colonial issues in the decades before 1914 that had left tensions high. And the cause of the public clashes can be traced to changes in the balance of power in Europe that had been taking place since 1866 with the rise of Prussia and its North German Confederation.[8]

Consensus on the origins of the war remains elusive, since historians disagree on key factors and place differing emphasis on a variety of factors. That is compounded by historical arguments changing over time, particularly as classified historical archives become available, and as perspectives and ideologies of historians have changed. The deepest division among historians is between those who see Germany and Austria-Hungary as having driven events and those who focus on power dynamics among a wider set of actors and circumstances. Secondary fault lines exist between those who believe that Germany deliberately planned a European war, those who believe that the war was largely unplanned but was still caused principally by Germany and Austria-Hungary taking risks, and those who believe that some or all of the other powers (Russia, France, Serbia, United Kingdom) played a more significant role in causing the war than has been traditionally suggested. However, there is a consensus among scholars that Germany was the biggest factor causing the war[9][10][11] and was also the country that escalated the war by drawing Britain and its colonies into the conflict with the invasion of Belgium. However, Germany had previously used diplomatic means with Russia and France to contain the situation but failed and Russia-France mobilized their forces first.[12][13][14][15] There is a popular view that this was an imperialist war between the two sides.

- ^ a b Van Evera, Stephen (Summer 1984). "The Cult of the Offensive and the Origins of the First World War". International Security. 9 (1): 58–107. doi:10.2307/2538636. JSTOR 2538636.

- ^ Fischer, Fritz (1975). War of illusions: German policies from 1911 to 1914. Chatto and Windus. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-3930-5480-4.

- ^ Snyder, Glenn H. (1984). "The Security Dilemma in Alliance Politics". World Politics. 36 (4): 461–495. doi:10.2307/2010183. ISSN 0043-8871. JSTOR 2010183. S2CID 154759602.

- ^ a b Jervis, Robert (1978). "Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma". World Politics. 30 (2): 167–214. doi:10.2307/2009958. hdl:2027/uc1.31158011478350. ISSN 0043-8871. JSTOR 2009958. S2CID 154923423.

- ^ Snyder, Jack (1984). "Civil-Military Relations and the Cult of the Offensive, 1914 and 1984". International Security. 9 (1): 108–146. doi:10.2307/2538637. ISSN 0162-2889. JSTOR 2538637. S2CID 55976453.

- ^ Sagan, Scott D. (Fall 1986). "1914 Revisited: Allies, Offense, and Instability". International Security. 11 (2): 151–175. doi:10.2307/2538961. JSTOR 2538961. S2CID 153783717.

- ^ Henig, Ruth (2006). The Origins of the First World War. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-85200-0.

- ^ Lieven, D. C. B. (1983). Russia and the Origins of the First World War. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-69611-5.

- ^ Annika Mombauer, "Guilt or Responsibility? The Hundred-Year Debate on the Origins of World War I." Central European History 48#4 (2015): 541–564, quote on p. 543.

- ^ Mombauer, p. 544

- ^ Paul W. Schroeder, "World War I as Galloping Gertie: A Reply to Joachim Remak," Journal of Modern History 44#3 (1972), pp. 319-345, at p. 320. JSTOR 1876415.

- ^ Martel 2014, p. 335.

- ^ Gilbert 1994, p. 27.

- ^ Lieven 2016, p. 326.

- ^ Clark 2013, pp. 526–527.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search