Back Slaapsiekte Afrikaans የአፍሪካ ፈንግል Amharic داء المثقبيات الإفريقي Arabic داء المثقبيات الافريقى ARZ Afrika tripanosomozu Azerbaijani Сонная хвароба Byelorussian Африканска трипанозомоза Bulgarian আফ্রিকান ট্রাইপানোসোমিয়াসিস Bengali/Bangla Tripanosomosi africana Catalan Spavá nemoc Czech

| African trypanosomiasis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sleeping sickness, African sleeping sickness |

| |

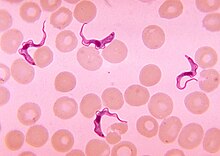

| Trypanosoma forms in a blood smear | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Stage 1: Fevers, headaches, itchiness, joint pains[1] Stage 2: Insomnia, confusion, Ataxia[2][1] |

| Usual onset | 1–3 weeks post exposure[2] |

| Types | Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (TbG), Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (TbR)[3] |

| Causes | Trypanosoma brucei spread by tsetse flies[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood smear, lumbar puncture[2] |

| Medication | Fexinidazole, pentamidine, suramin, melarsoprol, eflornithine, nifurtimox[3] |

| Prognosis | Fatal without treatment[3] |

| Frequency | 977 (2018)[3] |

| Deaths | 3,500 (2015)[4] |

African trypanosomiasis, also known as African sleeping sickness or simply sleeping sickness, is an insect-borne parasitic infection of humans and other animals.[3] It is caused by the species Trypanosoma brucei.[3] Humans are infected by two types, Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (TbG) and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (TbR).[3] TbG causes over 92% of reported cases.[1] Both are usually transmitted by the bite of an infected tsetse fly and are most common in rural areas.[3]

Initially, the first stage of the disease is characterized by fevers, headaches, itchiness, and joint pains, beginning one to three weeks after the bite.[1][2] Weeks to months later, the second stage begins with confusion, poor coordination, numbness, and trouble sleeping.[2] Diagnosis is by finding the parasite in a blood smear or in the fluid of a lymph node.[2] A lumbar puncture is often needed to tell the difference between first- and second-stage disease.[2] If the disease is not treated quickly it can lead to death.

Prevention of severe disease involves screening the at-risk population with blood tests for TbG.[3] Treatment is easier when the disease is detected early and before neurological symptoms occur.[3] Treatment of the first stage has been with the medications pentamidine or suramin.[3] Treatment of the second stage has involved eflornithine or a combination of nifurtimox and eflornithine for TbG.[2][3] Fexinidazole is a more recent treatment that can be taken by mouth, for either stage of TbG.[3] While melarsoprol works for both types, it is typically only used for TbR, due to serious side effects.[3] Without treatment, sleeping sickness typically results in death.[3]

The disease occurs regularly in some regions of sub-Saharan Africa with the population at risk being about 70 million in 36 countries.[5] An estimated 11,000 people are currently infected with 2,800 new infections in 2015.[6][1] In 2018 there were 977 new cases.[3] In 2015 it caused around 3,500 deaths, down from 34,000 in 1990.[4][7] More than 80% of these cases are in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[1] Three major outbreaks have occurred in recent history: one from 1896 to 1906 primarily in Uganda and the Congo Basin, and two in 1920 and 1970, in several African countries.[1] It is classified as a neglected tropical disease.[8] Other animals, such as cows, may carry the disease and become infected in which case it is known as Nagana or animal trypanosomiasis.[1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h WHO Media centre (March 2014). "Fact sheet N°259: Trypanosomiasis, Human African (sleeping sickness)". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kennedy PG (February 2013). "Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness)". The Lancet. Neurology. 12 (2): 186–194. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70296-X. PMID 23260189. S2CID 8688394.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Trypanosomiasis, human African (sleeping sickness)". www.who.int. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ a b Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Simarro PP, Cecchi G, Franco JR, Paone M, Diarra A, Ruiz-Postigo JA, et al. (2012). "Estimating and mapping the population at risk of sleeping sickness". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (10): e1859. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001859. PMC 3493382. PMID 23145192.

- ^ Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–2128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMC 10790329. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253.

- ^ "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search