Back كتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة Arabic Compendi de càlcul per reintegració i comparació Catalan جەبر و موقابەلە CKB Hisab al-dschabr wa-l-muqabala German Compendio de cálculo por reintegración y comparación Spanish Al-Kitab al-Jabr wa-l-Muqabala Basque الجبر والمقابله Persian Abrégé du calcul par la restauration et la comparaison French किताब-अल-जबर-वल-मुक़ाबला Hindi Әл-Жәбр уә-л-мұқабала Kazakh

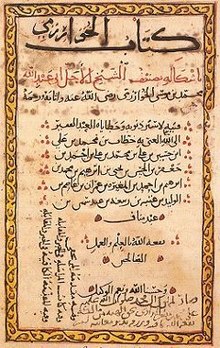

Title page, 9th century | |

| Author | Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi |

|---|---|

| Original title | كتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة |

| Illustrator | Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi |

| Language | Arabic |

| Subject | Algebra[a] |

| Genre | Mathematics |

Publication date | 820 |

| Publication place | Abbasid Caliphate |

Original text | كتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة at Arabic Wikisource |

| Translation | The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing at Wikisource |

Al-Jabr (Arabic: الجبر), also known as The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing (Arabic: الكتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة, al-Kitāb al-Mukhtaṣar fī Ḥisāb al-Jabr wal-Muqābalah;[b] or Latin: Liber Algebræ et Almucabola), is an Arabic mathematical treatise on algebra written in Baghdad around 820 by the Persian polymath Al-Khwarizmi. It was a landmark work in the history of mathematics, with its title being the ultimate etymology of the word "algebra" itself, later borrowed into Medieval Latin as algebrāica.

Al-Jabr provided an exhaustive account of solving for the positive roots of polynomial equations up to the second degree.[1]: 228 [c] It was the first text to teach elementary algebra, and the first to teach algebra for its own sake.[d] It also introduced the fundamental concept of "reduction" and "balancing" (which the term al-jabr originally referred to), the transposition of subtracted terms to the other side of an equation, i.e. the cancellation of like terms on opposite sides of the equation.[e] Mathematics historian Victor J. Katz regards Al-Jabr as the first true algebra text that is still extant.[f] Translated into Latin by Robert of Chester in 1145, it was used until the sixteenth century as the principal mathematical textbook of European universities.[4][g][6][7]

Several authors have also published texts under this name, including Abu Hanifa Dinawari, Abu Kamil, Abū Muḥammad al-ʿAdlī, Abū Yūsuf al-Miṣṣīṣī, 'Abd al-Hamīd ibn Turk, Sind ibn ʿAlī, Sahl ibn Bišr, and Šarafaddīn al-Ṭūsī.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Boyer, Carl B. (1991). "The Arabic Hegemony". A History of Mathematics (Second ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-54397-7.

- ^ Gandz; Saloman (1936). The sources of al-Khwarizmi's algebra. Vol. I. Osiris. pp. 263–277.

- ^ Katz, Victor J.; Barton, Bill (December 2006). "Stages in the history of algebra with implications for teaching". Educational Studies in Mathematics. 66 (2): 185–201. doi:10.1007/s10649-006-9023-7. See p. 190.

- ^ Philip Khuri Hitti (2002). History of the Arabs. Macmillan International Higher Education. pp. 379. ISBN 9780333631423.

- ^ Fred James Hill, Nicholas Awde (2003). A History of the Islamic World. Hippocrene Books. pp. 55. ISBN 9780781810159.

- ^ Overbay, Shawn; Schorer, Jimmy; Conger, Heather. "Al-Khwarizmi". University of Kentucky.

- ^ "Islam Spain and the history of technology". www.sjsu.edu. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search