This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Appalachian temperate rainforest | |

|---|---|

The Appalachian Trail traverses the dense, moss-covered spruce-fir understory near the summit of Old Black in the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee. | |

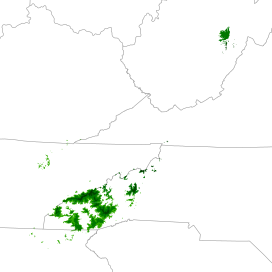

Areas in Appalachia that meet the climatic criteria of a temperate rainforest[a] | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Nearctic |

| Biome | Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests |

| Bird species | >240[4] |

| Mammal species | 68[5] |

| Geography | |

| Country | United States |

| Elevation | Up to 6,684 feet (2,037 m) |

| Climate type | Oceanic climate (Cfb) and humid continental (Dfb)[6] |

The Appalachian temperate rainforest or Appalachian cloud forest is located in the southern Appalachian Mountains of the eastern United States and is among the most biodiverse temperate regions in the world.[5][7] Centered primarily around Southern Appalachian spruce–fir forests between southwestern Virginia and southwestern North Carolina, it has a cool, mild climate with highly variable temperature and precipitation patterns linked to elevation.[8][9] The temperate rainforest as a whole has a mean annual temperature near 7 °C (45 °F) and annual precipitation exceeding 140 centimeters (55 in), though the highest peaks can reach more than 200 centimeters (79 in) and are frequently shrouded in fog.[8][10]

Due to variable microclimates across different elevations, the rainforest is able to support both southern and northern species, including some which were forced south during the Last Ice Age.[5][7][11] Dominated by evergreen spruce and fir forests at higher elevations and deciduous cove forests at lower elevations, the ecosystem contains thousands of plant species, including epiphytes, orchids, and numerous mosses and ferns.[12][13][14][15] It is also home to many animals and fungi, including endangered and endemic species, reaching the highest diversities of mushrooms, salamanders, land snails, and millipedes in the world.[5][7]

Humans have shaped the rainforest environment for the last 12,000 years through activities such as hunting and agriculture.[16] These impacts grew following European colonization, which brought about significant changes, including the decline of native populations, land use alterations, and the introduction of non-native species.[16] By the 1880s, industrialization reached the region, leaving the forest devastated by mining, logging and the introduction of destructive invasive species, examples being chestnut blight and the balsam woolly adelgid.[16][17][18][19] Conservation efforts such as the establishment of national forests and parks have helped preserve the ecosystem, however, it continues to face ongoing threats such as wildfire and climate change.[19][20][21]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Alabackwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ DellaSala, Dominick A. Temperate and Boreal Rainforests of the World: Ecology and Conservation. Washington, DC: Island, 2011. Print.

- ^ "Historical Climate Data". WorldClim. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ "Great Smoky Mountains Birds". National Park Service. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Great Smoky Mountains Nature & Science". National Park Service. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ H. E. Beck; T. R. McVicar; N. Vergopolan; A. Berg; N. J. Lutsko; A. Dufour; Z. Zeng; X. Jiang; A. I. J. M. van Dijk; D. G. Miralles (2023). "High-resolution (1 km) Köppen-Geiger maps for 1901–2099 based on constrained CMIP6 projections". National Weather Digest. 10 (1). Scientific Data: 724. Bibcode:2023NatSD..10..724B. doi:10.1038/s41597-023-02549-6. PMC 10593765. PMID 37872197.

- ^ a b c "Biodiversity of Highlands". Highlands Biological Station. 14 December 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b "Leaf Gas Exchange of Understory Spruce–fir Saplings in Relict Cloud Forests, Southern Appalachian Mountains, USA." Reinhardt, Keith, and William K. Smith. Tree Physiology 28 (2007): 113-22.

- ^ "Weather". Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ David M. Gaffin; David G. Hotz (2000). "A Precipitation and Flood Climatology with Synoptic Features of Heavy Rainfall across the Southern Appalachian Mountains" (PDF). National Weather Digest. 24 (3): 3–15.

- ^ "Geologic Provinces of the United States: Appalachian Highlands Province." Archived 2013-03-11 at the Wayback Machine USGS Geology in the Parks. N.p., 13 Jan. 2004. Web. 1 Oct. 2013.

- ^ Creed, I. F., D. L. Morrison, and N. S. Nicholas. "., Is Coarse Woody Debris a Net Sink or Source of Nitrogen in the Red Spruce – Fraser Fir Forest of the Southern Appalachians, U.S.A.?" National Research Council Canada 24 (2004): 716-27. Print.

- ^ "Land of the Great Forests". National Park Service. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Bentleywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Epiphytewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Historywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

FraserFirwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

EarthDaywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

NPSHistorywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

WeeksActwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Conferencewas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search