Back تشارلز إي. باربر Arabic تشارلز اى. باربر ARZ Charles E. Barber Spanish Charles E. Barber French Charles E. Barber Galician Charles Edward Barber Italian Charles Barber Polish 查尔斯·爱德华·巴伯 Chinese

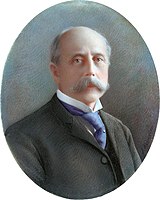

Charles E. Barber | |

|---|---|

| |

| 6th Chief Engraver of the U.S. Mint | |

| In office January 20, 1880 – February 18, 1917 | |

| President | List of presidents

|

| Preceded by | William Barber |

| Succeeded by | George T. Morgan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Charles Edward Barber November 16, 1840[1] London, England |

| Died | February 18, 1917 (aged 76) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Resting place | Mount Peace Cemetery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Occupation | Engraver |

Charles Edward Barber (November 16, 1840 – February 18, 1917) was an American coin engraver who served as the sixth chief engraver of the United States Mint from 1879 until his death in 1917. He had a long and fruitful career in coinage, designing most of the coins produced at the mint during his time as chief engraver. He did full coin designs, and he designed about 30 medals in his lifetime.[2] The Barber coinage were named after him. In addition, Barber designed a number of commemorative coins, some in partnership with assistant engraver George T. Morgan. For the popular Columbian half dollar, and the Panama-Pacific half dollar and quarter eagle, Barber designed the obverse and Morgan the reverse. Barber also designed the 1883 coins for the Kingdom of Hawaii, and also Cuban coinage of 1915. Barber's design on the Cuba 5 centavo coin remained in use until 1961.

While much has been written about Barber being disagreeable and even hostile to Morgan, this has been conclusively disproved, with concrete evidence that the two had a warm personal relationship over their 40 years of closely working together.[3][4]

Contrary to wide belief, Barber also had a warm personal relationship with President Theodore Roosevelt. While it is true that Roosevelt wanted U.S. coinage in the new century to have a more modern look, and also solicited designs from artists outside the U.S. Mint, this does not mean that he had a personal dislike of the man. The descendants of Charles Barber possess artifacts that prove a warm personal relationship existed.[3][4]

At the request of President Roosevelt and Mint director George E. Roberts, Barber made a trip to Europe to visit a number of foreign mints on an information-sharing mission. His goal was to observe and discuss the practices at the foreign mints to look for ways to improve operations and efficiency at the U.S. Mint. He combined this trip with a family vacation with his second wife Caroline and his 19-year-old daughter Edith. Barber carried with him memos from various departments within the mint with questions to ask their counterparts overseas. These memos, some of which today have Barber's hand-written notes, correspond to the various reports he submitted to Mint director Roberts after his return (these reports are in the National Archives). Edith's diary from the trip provide details on their itinerary and personal reflections on her father.[5]

Barber was known to be a meticulous professional. While different people have varying opinions about the artistic merits of his designs, it is indisputable that his coin designs hold up to years of heavy use and wear. This is one reason that so many Barber coins exist in such low grades—they were real workhorses in the U.S. economy and were routinely found in circulation until the 1950s.

- ^ "Charles E. Barber". Nps.gov.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Charles Barber". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Frost, John (Fall 2018). "In Search of Charles Barber, Part 3 - Rewriting the History Books". Journal of the Barber Coin Collectors' Society. 29, #3: 20–29.

- ^ a b Frost, John (August 2018). The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association. pp. 49–61.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Frost, John (Summer 2018). "Searching for Charles Barber, Part 2 - The European Trip of 1905". Journal of the Barber Coin Collectors' Society. 29: 20–29.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search