Back Clotilda (Schiff) German Clotilda (barco negrero) Spanish Clotilda Finnish Clotilda (navire) French קלוטילדה (ספינת עבדים) HE Clotilda (kapal pengangkut budak) ID クロティルダ (奴隷船) Japanese Clotilda (schip) Dutch

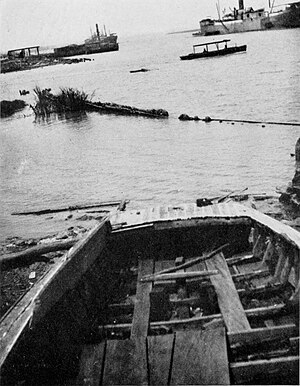

Wreck of the slave ship Clotilda; photograph from Historic Sketches of the South by Emma Langdon Roche, 1914

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Clotilda |

| Owner | Timothy Meaher |

| Launched | c. 1855–56 |

| Fate | Scuttled in July 1860 |

| Notes | Last known U.S. slave ship to bring captives from Africa to the United States |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | lumber trade |

| Length | 86 ft (26 m) |

| Beam | 23 ft (7.0 m) |

| Sail plan | Schooner |

The schooner Clotilda (often misspelled Clotilde) was the last known U.S. slave ship to bring captives from Africa to the United States, arriving at Mobile Bay, in autumn 1859[1] or on July 9, 1860,[2][3] with 110 African men, women, and children.[4] The ship was a two-masted schooner, 86 feet (26 m) long with a beam of 23 ft (7.0 m).

U.S. involvement in the Atlantic slave trade had been banned by Congress through the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves enacted on March 2, 1807 (effective January 1, 1808), but the practice continued illegally. In the case of the Clotilda, the voyage's sponsors were based in the South and planned to buy Africans in Whydah, Dahomey.[1][2] After the voyage, the ship was burned and scuttled in Mobile Bay in an attempt to destroy the evidence.

After the Civil War, Oluale Kossola[1] and thirty-one other formerly enslaved people founded Africatown on the north side of Mobile, Alabama. They were joined by other continental Africans and formed a community that continued to practice many of their West African traditions and Yoruba language for decades.

A spokesman for the community, Cudjo Lewis, lived until 1935 and was one of the last survivors from the Clotilda. Redoshi, another captive on the Clotilda, was sold to a planter in Dallas County, Alabama, where she became known also as Sally Smith. She married, had a daughter, and lived until 1937 in Bogue Chitto. She was long thought to have been the last survivor of the Clotilda.[5] Research published in 2020 indicated that another survivor, Matilda McCrear, lived until 1940.[6]

Some 100 descendants of the enslaved people carried by the Clotilda still live in Africatown, and others are around the country. After World War II, the neighborhood was absorbed by the city of Mobile. A memorial bust of Lewis was placed in front of the historic Union Missionary Baptist Church.[2] The Africatown historic district was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2012. In May 2019, the Alabama Historical Commission announced that remnants of a ship found along the Mobile River, near 12 Mile Island and just north of the Mobile Bay delta, were confirmed as the Clotilda.[7] The wreck site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2021.[8]

- ^ a b c David Pilgrim. "Question of the Month: Cudjo Lewis: Last African Slave in the U.S.?" Jim Crow Museum, Ferris University, July 2005.

- ^ a b c "Black Travel - Soul Of America | Home" (historic sites), Soul of America, 2007, webpage: SoulofAmerica-6678.

- ^ "AfricaTown, USA". The American Folklife Center: Local Legacies. The Library of Congress. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ^ Raines, Ben (2022). The Last Slave Ship: The True Story of How Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. p. 69. ISBN 9781982136048.

- ^ Durkin, Hannah (March 26, 2019). "Finding last middle passage survivor Sally 'Redoshi' Smith on the page and screen". Slavery & Abolition. 40 (4): 631–658. doi:10.1080/0144039X.2019.1596397. S2CID 150975893.

- ^ Durkin, Hannah (March 19, 2020). "Uncovering The Hidden Lives of Last Clotilda Survivor Matilda McCrear and Her Family". Slavery & Abolition. 41 (3): 431–457. doi:10.1080/0144039X.2020.1741833. ISSN 0144-039X. S2CID 216497607.

- ^ Keyes, Allison (May 22, 2019). "The 'Clotilda,' the Last Known Slave Ship to Arrive in the U.S., Is Found". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ "Weekly listing". National Park Service.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search