Back باز كوبر Arabic صقر كوبر ARZ Accipiter cooperii AST Accipiter cooperii Azerbaijani Accipiter cooperii Bulgarian Accipiter cooperii Breton Astor de Cooper Catalan Accipiter cooperii CEB Jestřáb Cooperův Czech Gwalch Cooper Welsh

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (February 2023) |

| Cooper's hawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Accipiter |

| Species: | A. cooperii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Accipiter cooperii (Bonaparte, 1828)

| |

| |

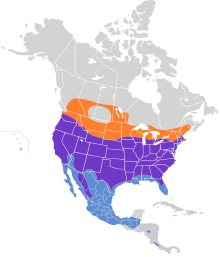

Breeding Year-round Nonbreeding

| |

Cooper's hawk (Accipiter cooperii) is a medium-sized hawk native to the North American continent and found from southern Canada to Mexico.[2] This species is a member of the genus Accipiter, sometimes referred to as true hawks, which are famously agile, relatively small hawks common to wooded habitats around the world and also the most diverse of all diurnal raptor genera.[2] As in many birds of prey, the male is smaller than the female.[3] The birds found east of the Mississippi River tend to be larger on average than the birds found to the west.[4] It is easily confused with the smaller but similar sharp-shinned hawk. (A. striatus)

The species was named in 1828 by Charles Lucien Bonaparte in honor of his friend and fellow ornithologist, William Cooper.[5] Other common names for Cooper's hawk include: big blue darter, chicken hawk, flying cross, hen hawk, quail hawk, striker, and swift hawk.[6] Many of the names applied to Cooper's hawks refer to their ability to hunt large and evasive prey using extremely well-developed agility. This species primarily hunts small-to-medium-sized birds, but will also commonly take small mammals and sometimes reptiles.[7][8]

Like most related hawks, Cooper's hawks prefer to nest in tall trees with extensive canopy cover and can commonly produce up to two to four fledglings depending on conditions.[2][5] Breeding attempts may be compromised by poor weather, predators and anthropogenic causes, in particular the use of industrial pesticides and other chemical pollution in the 20th century.[7][9] Despite declines due to manmade causes, the bird remains a stable species.[1]

- ^ a b BirdLife International (2016). "Accipiter cooperii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22695656A93521264. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695656A93521264.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c Ferguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D. (2001). Raptors of the World. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-0-7136-8026-3.

- ^ Snyder, N. F., & Wiley, J. W. (1976). Sexual size dimorphism in hawks and owls of North America (No. 20). American Ornithologists' Union.

- ^ Pearlstine, E. V., & Thompson, D. B. (2004). Geographic variation in morphology of four species of migratory raptors. Journal of Raptor Research, 38(4), 334–342.

- ^ a b Palmer, R. S., ed. (1988). Handbook of North American birds. Volume 5 Diurnal Raptors (part 2).

- ^ Bent, A. C. 1938. Life histories of North American birds of prey, Part 1. U.S. National Museum Bulletin 170:295–357.

- ^ a b Rosenfield, R. N., K. K. Madden, J. Bielefeldt & Curtis, O.E. (2019). Cooper's Hawk (Accipiter cooperii), version 3.0. In The Birds of North America (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- ^ Toland, Brian (1985). "Food Habits and Hunting Success of Cooper's Hawks in Missouri" (PDF). Journal of Field Ornithology. 56 (4): 419–422. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Snyder, N. F. R. (1974). Can the Cooper's Hawk survive? National Geographic Magazine, 145:432–442.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search