Back Bedreigde taal Afrikaans Bedrohte Sprache ALS لغة مهددة بالانقراض Arabic বিলুপ্তপ্ৰায় ভাষা Assamese Idioma amenazáu AST Dillərin yaşaması dərəcəsi Azerbaijani Tataramon na Nawawara na BCL Ступень захаванасці мовы Byelorussian Загрожаная мова BE-X-OLD Застрашен език Bulgarian

An endangered language or moribund language is a language that is at risk of disappearing as its speakers die out or shift to speaking other languages.[1] Language loss occurs when the language has no more native speakers and becomes a "dead language". If no one can speak the language at all, it becomes an "extinct language". A dead language may still be studied through recordings or writings, but it is still dead or extinct unless there are fluent speakers.[2] Although languages have always become extinct throughout human history, they are currently dying at an accelerated rate because of globalization, mass migration, cultural replacement, imperialism, neocolonialism[3] and linguicide (language killing).[4][better source needed]

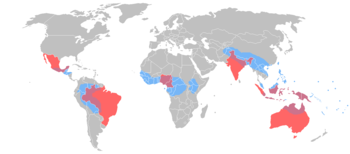

Language shift most commonly occurs when speakers switch to a language associated with social or economic power or one spoken more widely, leading to the gradual decline and eventual death of the endangered language. The process of language shift is often influenced by factors such as globalisation, economic authorities, and the perceived prestige of certain languages. The ultimate result is the loss of linguistic diversity and cultural heritage within affected communities. The general consensus is that there are between 6,000[5] and 7,000 languages currently spoken. Some linguists estimate that between 50% and 90% of them will be severely endangered or dead by the year 2100.[3] The 20 most common languages, each with more than 50 million speakers, are spoken by 50% of the world's population, but most languages are spoken by fewer than 100,000,000 people.[3]

The first step towards language death is potential endangerment. This is when a language faces strong external pressure, but there are still communities of speakers who pass the language to their children. The second stage is endangerment. Once a language has reached the endangerment stage, there are only a few speakers left and children are, for the most part, not learning the language. The third stage of language extinction is seriously endangered. During this stage, a language is unlikely to survive another generation and will soon be extinct. The fourth stage is moribund, followed by the fifth stage extinction.

Many projects are under way aimed at preventing or slowing language loss by revitalizing endangered languages and promoting education and literacy in minority languages, often involving joint projects between language communities and linguists.[6] Across the world, many countries have enacted specific legislation aimed at protecting and stabilizing the language of indigenous speech communities. Recognizing that most of the world's endangered languages are unlikely to be revitalized, many linguists are also working on documenting the thousands of languages of the world about which little or nothing is known.

- ^ "What Is an Endangered Language? | Linguistic Society of America". www.linguisticsociety.org. Archived from the original on 2022-03-23. Retrieved 2023-07-24.

- ^ Crystal, David (2002). Language Death. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 0521012716.

A language is said to be dead when no one speaks it any more. It may continue to have existence in a recorded form, of course traditionally in writing, more recently as part of a sound or video archive (and it does in a sense 'live on' in this way) but unless it has fluent speakers one would not talk of it as a 'living language'.

- ^ a b c Austin, Peter K; Sallabank, Julia (2011). "Introduction". In Austin, Peter K; Sallabank, Julia (eds.). Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88215-6.

- ^ See pp. 55-56 of Zuckermann, Ghil'ad, Shakuto-Neoh, Shiori & Quer, Giovanni Matteo (2014), Native Tongue Title: Proposed Compensation for the Loss of Aboriginal Languages, Australian Aboriginal Studies 2014/1: 55-71.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Moseleywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Grinevald, Collette & Michel Bert. 2011. "Speakers and Communities" in Austin, Peter K; Sallabank, Julia, eds. (2011). Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88215-6. p.50

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search