Back أفضلية الحركة الأولى في الشطرنج Arabic Предимство на първия ход в шахмата Bulgarian Avantatge del primer moviment en escacs Catalan Výhoda prvního tahu v šachu Czech Anziehender German Ventaja de salida en ajedrez Spanish Ensimmäisen siirron etu shakissa Finnish Avantage du trait aux échecs French יתרון מהלך ראשון בשחמט HE Առաջին քայլի առավելությունը շախմատում Armenian

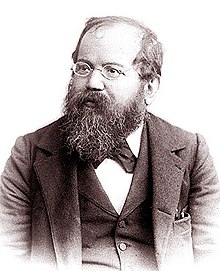

In chess, there is a consensus among players and theorists that the player who makes the first move (White) has an inherent advantage, albeit not one large enough to win with perfect play. This has been the consensus since at least 1889, when the first World Chess Champion, Wilhelm Steinitz, addressed the issue, although chess has not been solved.

Since 1851, compiled statistics support this view; White consistently wins slightly more often than Black, usually achieving a winning percentage between 52 and 56 percent.[nb 1] White's advantage is less significant in blitz games and games between lower-level players, and becomes greater as the level of play rises; however, raising the level of play also increases the percentage of draws. As the standard of play rises, all the way up to top engine level, the number of decisive games approaches zero, and the proportion of White wins among those decisive games approaches 100%.[1]

Some players, including world champions such as José Raúl Capablanca, Emanuel Lasker, Bobby Fischer, and Vladimir Kramnik, have expressed fears of a "draw death" as chess becomes more deeply analyzed, and opening preparation becomes ever more important. To alleviate this danger, Capablanca, Fischer, and Kramnik proposed chess variants to revitalize the game, while Lasker suggested changing how draws and stalemates are scored. Several of these suggestions have been tested with engines: in particular, Larry Kaufman and Arno Nickel's extension of Lasker's idea – scoring being stalemated, bare king, and causing a threefold repetition as quarter-points – shows by far the greatest reduction of draws among the options tested, and Fischer random chess (which obviates preparation by randomising the starting array) has obtained significant uptake at top level.

Some writers have challenged the view that White has an inherent advantage. András Adorján wrote a series of books on the theme that "Black is OK!", arguing that the general perception that White has an advantage is founded more in psychology than reality. Though computer analysis disagrees with his wider claim, it agrees with Adorján that some openings are better than others for Black, and thoughts on the relative strengths of openings have long informed the opening choices in games between top players. Mihai Suba and others contend that sometimes White's initiative disappears for no apparent reason as a game progresses. The prevalent style of play for Black today is to seek unbalanced, dynamic positions with active counterplay, rather than merely trying to equalize. Modern writers also argue that Black has certain countervailing advantages. The consensus that White should try to win can be a psychological burden for the White player, who sometimes loses by trying too hard to win. Some symmetrical openings (i.e. those where Black's moves mirror White's) can lead to situations where moving first is a detriment, for either psychological or objective reasons.

Cite error: There are <ref group=nb> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=nb}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search