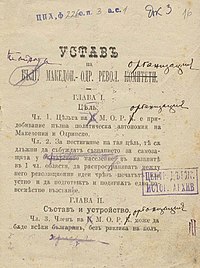

Statute of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees

Chapter I. – Goal

Art. 1. The goal of BMARC is to secure full political autonomy for the Macedonia and Adrianople regions .

Art. 2. To achieve this goal they [the committees] shall raise the awareness of self-defense in the Bulgarian population in the regions mentioned in Art. 1., disseminate revolutionary ideas – printed or verbal, and prepare and carry on a general uprising.

Chapter II. – Structure and Organization

Art. 3. A member of BMARC can be any Bulgarian, independent of gender, ...

Due to the lack of original protocol documentation, and the fact its early organic statutes were not dated, the first statute of the clandestine Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) is uncertain and is a subject to dispute among researchers. The dispute also includes its first name and ethnic character, as well as the authenticity, dating, validity, and authorship of its supposed first statute.[11] Certain contradictions and inconsistencies exist in the testimonies of the founding and other early members of the Organization, which further complicates the solution of the problem. It is not yet clear whether the earliest statutory documents of the Organization have been discovered. Its earliest basic documents discovered for now, became known to the historical community during 1960s.

The revolutionary organization set up in 1893 in Ottoman Thessaloniki changed its name several times before adopting in 1919 its last and most common name i.e. Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO).[12] The repeated changes of name of the IMRO has led to an ongoing debate between Bulgarian and Macedonian historians, as well as within the Macedonian historiographical community.[13] The crucial question is to which degree the Organization had a Bulgarian ethnic character and when it tried to open itself to the other Balkan nationalities.[14] As a whole, its founders were inspired by the earlier Bulgarian revolutionary traditions.[15] All its basic documents were written in the pre-1945 Bulgarian orthography.[16] The first statute of the IMRO from 1894 was modelled after the statute of the earlier Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee (BRCC).[17] IMRO adopted from BRCC also its symbol: the lion, and its motto: Svoboda ili smart.[18]

On the eve of the 20th century IMRO was often called "the Bulgarian Committee",[19][20] while its members were designated as Comitadjis, i.e. "committee men".[21] In the earliest dated samples of statutes and regulations of the Organization discovered so far, it is called Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Committees (BMARC).[note 1][22][23][24] These documents refer to the then Bulgarian population in the Ottoman Empire, which was to be prepared for a general uprising in Macedonia and Adrianople regions, aiming to achieve political autonomy for them.[25][26] In thе statute of BMARC, that is presumably the first one,[27][28] the membership was reserved exclusively for Bulgarians.[29] This ethnic restriction matches with the memoirs of some founding and ordinary members, where is mentioned such a requirement, set only in the Organization's first statute.[30] The name of BMARC, as well as information about its statute, was mentioned in the foreign press of that time, in Bulgarian diplomatic correspondence, and exists in the memories of some revolutionaries and contemporaries.[31]

- ^ "The Macedonian Revolutionary Organization used the Bulgarian standard language in all its programmatic statements and its correspondence was solely in the Bulgarian language...After 1944 all the literature of Macedonian writers, memoirs of Macedonian leaders, and important documents had to be translated from Bulgarian into the newly invented Macedonian." For more see: Bernard A. Cook ed., Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia, Volume 2, Taylor & Francis, 2001, ISBN 0815340583, p. 808.

- ^ Bulgarian researcher Tsocho Bilyarski claims that the corrections were made by Delchev, but according to the Bulgarian historian Dino Kyosev, this handwriting is Poparsov's style. For more see: Цочо Билярски, Още един път за първите устави и правилници и за името на ВМОРО преди Илинденско-Преображенското Въстание от 1903 г. В сборник Дойно Дойнов. 75 години наука, мъдрост и достойнство, събрани в един живот. ВСУ "Черноризец Храбър"; 2004, ISBN 9549800407.

- ^ The change was reflected in the revised IO statutes of 1902 which dropped 'Bulgarian' from the title ; this was now TMORO , and appealed to all dissatisfied elements in Macedonia, not merely Bulgarian ones. For more see: Hugh Poulton, Who are the Macedonians? 2000, Hurst,ISBN 9781850655343, p. 55.

- ^ Kat Kearey (2015) Oxford AQA History: A Level and AS Component 2: International Relations and Global Conflict C1890-1941. ISBN 9780198363866, p. 54.

- ^ Иван Катарџиев, Борба до победа. Студии и статии. Скопjе, Мисла; 1983 г., стр. 65.

- ^ сп. "Македония", Том 1, София, 1922, стр. 5. Digitized on 15 April 2013 at Cornell University.

- ^ Except from the Rules (the oath) of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (in English) in Macedonia Documents and Material, 1978 by Bozhinov, Voin & L. Panayotov. Sofia, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

- ^ Спиро Гулабчев - "Причините, които зародиха револ. организация остават незачекнати; Организацията (ръкопис - II част)", София, ок. 1904 година. Атанас Струмски, Библиотека и Издателство "Струмски".

- ^ Ѓорѓиев, Ванчо, Петар Поп Арсов (1868–1941). Прилог кон проучувањето на македонското националноослободително движење. 1997, Скопjе, стр. 61.

- ^ Книги и Материјали за Македонија, Алексо Мартулков, Моето учество во револуционерните борби на Македонија.

- ^ Marinov, Tchavdar. We, the Macedonians: The Paths of Macedonian Supra-Nationalism (1878–1912) In: We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9786155211669. pp. 114-115.

- ^ Raymond Detrez, Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria; Historical Dictionaries of Europe; Rowman & Littlefield, 2014, ISBN 1442241802, p. 253-254.

- ^ Alexis Heraclides, The Macedonian Question and the Macedonians: A History. Routledge, 2020, ISBN 9780367218263, pp. 40-41.

- ^ Vemund Aarbakke (2003) Ethnic rivalry and the quest for Macedonia, 1870-1913, East European Monographs, ISBN 9780880335270, p. 97.

- ^ IMRO group modelled itself after the revolutionary organizations of Vasil Levski and other noted Bulgarian revolutionaries like Hristo Botev and Georgi Benkovski, each of whom was a leader during the earlier Bulgarian revolutionary movement. Around this time ca. 1894, a seal was struck for use by the Organization leadership; it was inscribed with the phrase "Freedom or Death" (Svoboda ili smart). For more see: Duncan M. Perry, The Politics of Terror: The Macedonian Liberation Movements, 1893–1903, Duke University Press, 1988, ISBN 0822308134, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Bernard A. Cook ed., Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia, Volume 2, Taylor & Francis, 2001, ISBN 0815340583, p. 808.

- ^ As a corollary, the first charter of the organization was a rough copy of the "Bulgarian revolutionary central committee's" charter which they found in the work of Zahari Stoyanov, Zapiski po bûlgarskite vûstania ["Descriptions of the Bulgarian Uprising"]. For more see: Tetsuya Sahara, The Macedonian Origin of Black Hand. (International Conference "Great War, Serbia, Balkans and Great Powers") Strategic Research Institute & The Institute of History Belgrade, 2015, pp. 401–425 (408).

- ^ J. Pettifer as ed., The New Macedonian Question, Springer, 1999 ISBN 0230535798, p. 236.

- ^ Dimitar Bechev, Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, Introduction, p. Iviii.

- ^ Tchavdar Marinov, Famous Macedonia, the Land of Alexander: Macedonian identity at the crossroads of Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian nationalism in Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies with Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov as ed., BRILL, 2013, ISBN 900425076X, p. 300.

- ^ The word komitadji is Turkish, meaning literally "committee man". It came to be used for the guerilla bands, which, subsidized by the governments of the Christian Balkan states, especially of Bulgaria. For more see: The Making of a New Europe: R.W. Seton-Watson and the Last Years of Austria-Hungary, Hugh Seton-Watson, Christopher Seton-Watson, Methuen, 1981, ISBN 0416747302, p. 71.

- ^ Poulton, Hugh (2000). Who are the Macedonians, Indiana University Press, ISBN 9780253213594 p. 53.

- ^ Dimitar Bechev, Historical dictionary of North Macedonia, 2019; Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 9781538119624, p. 11.

- ^ Denis Š. Ljuljanović (2023) Imagining Macedonia in the Age of Empire. State Policies, Networks and Violence (1878–1912), LIT Verlag Münster; ISBN 9783643914460, p. 211.

- ^ Tunçay, Mete, and Erik J. Zürcher, eds. (1994) Socialism and Nationalism in the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 1850437874, p. 33.

- ^ MacDermott, Mercia (1978) Freedom or Death: The Life of Gotsé Delchev. West Nyack, N.Y.: Journeyman Press, pp. 144-149.

- ^ Vladimir Cretulescu (2016) "The Memoirs of Cola Nicea: A Case-Study on the Discursive Identity Construction of the Aromanian Armatoles in Early 20th Century Macedonia." Res Historica 41, p. 128.

- ^ Alexander Maxwell, "Slavic Macedonian Nationalism: From 'Regional' to 'Ethnic'", In Klaus Roth and Ulf Brunnbauer (eds.), Region, Regional Identity and Regionalism in Southeastern Europe, Volume 1 (Münster: LIT Verlag, 2008), ISBN 9783825813871, p. 135.

- ^ Victor Roudometof (2002) Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict. Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question. Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 9780275976484, p. 112.

- ^ Alexis Heraclides, The Macedonian Question and the Macedonians: A History. Routledge, 2020, ISBN 9780367218263, p. 240.

- ^ Цочо Билярски, Още един път за първите устави и правилници и за името на ВМОРО преди Илинденско-Преображенското Въстание от 1903 г. В сборник Дойно Дойнов. 75 години наука, мъдрост и достойнство, събрани в един живот. ВСУ "Черноризец Храбър"; 2004, ISBN 9549800407.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search