Back تقاطعات الفجوة بين الخلايا Arabic Unions comunicants Catalan Mezerový spoj Czech Gap Junction German Unión gap Spanish Gap lotura Basque اتصالات شکافدار Persian Aukkoliitos Finnish Jonction communicante French Unión comunicante Galician

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (April 2024) |

| Gap junction | |

|---|---|

Vertebrate gap junction | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D017629 |

| TH | H1.00.01.1.02024 |

| FMA | 67423 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

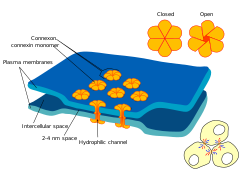

Gap junctions are one of three broad categories of intercellular connections that form between several animal cell types.[1][2] They were first imaged using an electron microscope circa 1952.[3][4] They were named in 1969[5] after the 2-4 nm gap they bridge between cell membranes.[6]

Gap junctions use protein complexes known as globules to connect one cell to another, and to connect vesicles within a cell to the outer cell membrane.[7] Globules are made of smaller protein components called connexins,[8][9] and six connexins form a channel called a connexon. There are over 26 different connexins, and at least 12 non-connexin components[10] that form the specialized area of membrane called the gap junction complex. These components include the protein ZO-1 which holds the membranes together,[11] sodium channels,[12] and aquaporin.[13][14]

More gap junction proteins have become known due to the development of next-generation sequencing. Connexins were found to be structurally homologous between vertebrates and invertebrates but different in sequence.[15] As a result, the term innexin is used to differentiate invertebrate connexins.[16] There are more than 20 known innexins,[17] along with unnexins in parasites and vinnexins in viruses.

Gap junctions are able to transmit action potentials between neurons. Connexon pairs act as generalized regulated gates for ions and smaller molecules between cells. Hemichannel connexons form channels to the extracellular environment.[18][19][20][21]

A gap junction may also be called a nexus or macula communicans. It should not be confused with an ephapse. While an ephapse, like a gap junction, involves the transmission of electrical signals, the two are distinct from each other because ephaptic coupling involves electrical signals external to the cells. Ephapses are often studied in the context of electrically induced potentials propagated among groups of nerve cell membranes, even in the absence of gap junction communication, with no discrete subcellular structures known.[22][23] Unlike gap junctions, no specific structure related to an ephapse has yet been described, so the process is often referred to as ephaptic coupling rather than as an ephapse.

- ^ Kelsell, David P.; Dunlop, John; Hodgins, Malcolm B. (2001). "Human diseases: clues to cracking the connexin code?". Trends in Cell Biology. 11 (1): 2–6. doi:10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01866-3. PMID 11146276.

- ^ Willecke, Klaus; Eiberger, Jürgen; Degen, Joachim; Eckardt, Dominik; Romualdi, Alessandro; Güldenagel, Martin; Deutsch, Urban; Söhl, Goran (2002). "Structural and functional diversity of connexin genes in the mouse and human genome". Biological Chemistry. 383 (5): 725–37. doi:10.1515/BC.2002.076. PMID 12108537. S2CID 22486987.

- ^ Robertson, J. D. (1952). Ultrastructure of an invertebrate synapse (Thesis). Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ^ Robertson, J. D. (1 February 1953). "Ultrastructure of Two Invertebrate Synapses". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 82 (2): 219–223. doi:10.3181/00379727-82-20071. PMID 13037850.

- ^ Brightman MW, Reese TS (March 1969). "Junctions between intimately apposed cell membranes in the vertebrate brain". J. Cell Biol. 40 (3): 648–677. doi:10.1083/jcb.40.3.648. PMC 2107650. PMID 5765759.

- ^ Revel, J. P.; Karnovsky, M. J. (1 June 1967). "Hexagonal Array of Subunits in Intercellular Junctions of the Mouse Heart and Liver". Journal of Cell Biology. 33 (3): C7–12. doi:10.1083/jcb.33.3.C7. PMC 2107199. PMID 6036535.

- ^ Peracchia, Camillo (1 April 1973). "Low Resistance Junctions in Crayfish". Journal of Cell Biology. 57 (1): 66–76. doi:10.1083/jcb.57.1.66. PMC 2108946. PMID 4120611.

- ^ Goodenough, Daniel A. (1 May 1974). "Bulk Isolation of Mouse Hepatocyte Gap Junctions". Journal of Cell Biology. 61 (2): 557–563. doi:10.1083/jcb.61.2.557. PMC 2109294. PMID 4363961.

- ^ Beyer, E C; Paul, D L; Goodenough, D A (1 December 1987). "Connexin43: a protein from rat heart homologous to a gap junction protein from liver". Journal of Cell Biology. 105 (6): 2621–2629. doi:10.1083/jcb.105.6.2621. PMC 2114703. PMID 2826492.

- ^ Hervé, Jean-Claude; Bourmeyster, Nicolas; Sarrouilhe, Denis; Duffy, Heather S. (May 2007). "Gap junctional complexes: From partners to functions". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 94 (1–2): 29–65. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.010. PMID 17507078.

- ^ Gilleron, Jérome; Carette, Diane; Fiorini, Céline; Benkdane, Merieme; Segretain, Dominique; Pointis, Georges (March 2009). "Connexin 43 gap junction plaque endocytosis implies molecular remodelling of ZO-1 and c-Src partners". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 2 (2): 104–106. doi:10.4161/cib.7626. PMC 2686357. PMID 19704902.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Localization of Na + channel clustewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Yu, Xun Sean; Yin, Xinye; Lafer, Eileen M.; Jiang, Jean X. (June 2005). "Developmental Regulation of the Direct Interaction between the Intracellular Loop of Connexin 45.6 and the C Terminus of Major Intrinsic Protein (Aquaporin-0)". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (23): 22081–22090. doi:10.1074/jbc.M414377200. PMID 15802270.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Gruijters, WTM 1989 509–13was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Phelan, Pauline; Stebbings, Lucy A.; Baines, Richard A.; Bacon, Jonathan P.; Davies, Jane A.; Ford, Chris (January 1998). "Drosophila Shaking-B protein forms gap junctions in paired Xenopus oocytes". Nature. 391 (6663): 181–184. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..181P. doi:10.1038/34426. PMID 9428764. S2CID 205003383.

- ^ Phelan, Pauline; Bacon, Jonathan P.; A. Davies, Jane; Stebbings, Lucy A.; Todman, Martin G. (September 1998). "Innexins: a family of invertebrate gap-junction proteins". Trends in Genetics. 14 (9): 348–349. doi:10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01547-9. PMC 4442478. PMID 9769729.

- ^ Ortiz, Jennifer; Bobkov, Yuriy V; DeBiasse, Melissa B; Mitchell, Dorothy G; Edgar, Allison; Martindale, Mark Q; Moss, Anthony G; Babonis, Leslie S; Ryan, Joseph F (3 February 2023). "Independent Innexin Radiation Shaped Signaling in Ctenophores". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 40 (2): msad025. doi:10.1093/molbev/msad025. PMC 9949713. PMID 36740225.

- ^ Furshpan, E. J.; Potter, D. D. (August 1957). "Mechanism of Nerve-Impulse Transmission at a Crayfish Synapse". Nature. 180 (4581): 342–343. Bibcode:1957Natur.180..342F. doi:10.1038/180342a0. PMID 13464833. S2CID 4216387.

- ^ Lampe, Paul D.; Lau, Alan F. (2004). "The effects of connexin phosphorylation on gap junctional communication". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 36 (7): 1171–86. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00264-4. PMC 2878204. PMID 15109565.

- ^ Lampe, Paul D.; Lau, Alan F. (2000). "Regulation of gap junctions by phosphorylation of connexins". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 384 (2): 205–15. doi:10.1006/abbi.2000.2131. PMID 11368307.

- ^ Scemes, Eliana; Spray, David C.; Meda, Paolo (April 2009). "Connexins, pannexins, innexins: novel roles of "hemi-channels"". Pflügers Archiv: European Journal of Physiology. 457 (6): 1207–1226. doi:10.1007/s00424-008-0591-5. PMC 2656403. PMID 18853183.

- ^ Martinez-Banaclocha, Marcos (13 February 2020). "Astroglial Isopotentiality and Calcium-Associated Biomagnetic Field Effects on Cortical Neuronal Coupling". Cells. 9 (2): 439. doi:10.3390/cells9020439. PMC 7073214. PMID 32069981.

- ^ Parker, David (22 December 2022). "Neurobiological reduction: From cellular explanations of behavior to interventions". Frontiers in Psychology. 13: 987101. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.987101. PMC 9815460. PMID 36619115.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search