Back القناة الصينية الكبرى Arabic القناه الصينيه الكبرى ARZ Gran Canal de China AST Grand Canal (Tsina) BCL Вялікі канал Кітая Byelorussian Велик китайски канал Bulgarian চীনের মহাখাল Bengali/Bangla Gran Canal (Xina) Catalan Grand Canal (kanal sa Pangmasang Republika sa Tśina, lat 39,90, long 116,73) CEB Velký kanál Czech

| Grand Canal of China | |

|---|---|

The canal in Beijing, by the Wanning Bridge. | |

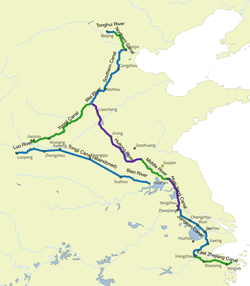

Courses of the Grand Canal | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 1,776 km (1,104 miles) |

| History | |

| Construction began | Sui dynasty |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Beijing |

| End point | Hangzhou |

| Connects to | Hai River, Yellow River, Huai River, Yangtze River, Qiantang River |

| Official name | The Grand Canal |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 2014 (38th session) |

| Reference no. | 1443 |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

| Grand Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Grand Canal" in simplified (top) and traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 大运河 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 大運河 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Great Transport River" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 京杭大运河 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 京杭大運河 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Grand Canal (Chinese: 大运河; pinyin: Dà yùnhé) is a system of interconnected canals linking various major rivers and lakes in North and East China, serving as an important waterborne transport infrastructure between the north and the south during Medieval and premodern China. It is the longest artificial waterway in the world and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Grand Canal has undergone several route changes throughout history. Its current main stem, known as the Jing–Hang Grand Canal, is thought to extend for 1,776 km (1,104 mi) linking Beijing in the north to Hangzhou in the south, and is divided into 6 main subsections, with the southernmost sections remaining relatively unchanged over time. The Jiangnan Canal starts from the Qiantang River at Hangzhou's Jianggan District, looping around the east side of Lake Tai through Jiaxing, Suzhou and Wuxi, to the Yangtze River at Zhenjiang; the Inner Canal from Yangzhou across the Yangtze from Zhenjiang, going through the Gaoyou Lake to join the Huai River at Huai'an, which for centuries was also its junction with the former course of the Yellow River; the Middle Canal from Huai'an to Luoma Lake at Suqian, then to the Nansi Lakes at Weishan; the Lu Canal from the Nansi Lakes at Jining and into the present course of the Yellow River at Liangshan, splitting off downstream at Liaocheng's Dong'e County before continuing to the Wei River at Linqing; the Southern Canal (named for its location within Hebei) from Linqing to the Hai River at Tianjin; and the Northern Canal from Tianjin to Tongzhou on the outskirts of Beijing. As such, it passes through the provinces of Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Shandong, Hebei, and the municipalities of Tianjin and Beijing. In 2014, the Chinese government and UNESCO recognized the Eastern Zhejiang Canal from Hangzhou to Ningbo along the former Tongji and Yongji Canals also as official components of the Grand Canal.

The oldest sections of what is now the Grand Canal were completed in the early 5th century BC during the conflicts of China's Spring and Autumn period to provide supplies and transport routes for the states of Wu and Yue. The network was expanded and completed by Emperor Yang of the Sui dynasty in AD 609, linking the fertile Jiangnan region in the south to his capital at Luoyang in the Central Plain and to his armies in the northern frontiers. His unsuccessful and unpopular northeastern wars against Goguryeo and the massive amounts of conscripted labor involved in creating the canals were among the chief factors in the rampant rebellions during his reign and the eventual rapid fall of the Sui dynasty, but the connection of China's major watersheds and population centers proved enormously beneficial during the subsequent Tang dynasty. Additional canals supplied Chang'an (now Xi'an) even further west were rebuilt under the Tang to better connect the Guanzhong heartland to the Central Plain, while stopover towns along the main course became the economic hubs of the empire. Sections of the canal gradually degraded and faded into ruins during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period and the Song dynasty, and periodic flooding of the Yellow River associated with climate changes during the Medieval Warm Period had erode d and threatened the safety and functioning of the canal while, during wartime, the rivers' high dikes were sometimes deliberately breached to delay or sweep away advancing enemy troops. Even so, restoration and improvement of the canal and its associated flood control works was assumed as a duty by each successive dynasty. The canal played a major role in periodically reuniting northern and southern China, and officials in charge of the canal and nearby salt works grew enormously wealthy. Despite damage from floods, rebellions and wars, the canal's importance only grew with the relocation of the national capital to Khanbaliq (now known as Beijing) under Kublai Khan during the Mongol Yuan dynasty, and again later under Yongle Emperor during the Ming dynasty and under Shunzhi Emperor the Manchu Qing dynasty. Despite the importance of railways and highways in modern times, the People's Republic of China has worked to improve the navigability of the canal since the end of the Chinese Civil War and the portion south of the Yellow River remains in heavy use by barges carrying bulk cargo. Increasing concern over pollution in China and particularly the use of the Grand Canal as the eastern path of the South-North Water Diversion Project—intended to provide clean potable water to the north—has led to regulations and several projects to improve water quality along the canals.

The greatest height on the canal is an elevation of 42 m (138 ft) above sea level reached in the foothills of Shandong province.[1] Ships in Chinese canals did not have trouble reaching higher elevations after the Song official and engineer Qiao Weiyue invented the pound lock in the 10th century.[2] The canal has been admired by many visitors throughout its history, including the Japanese monk Ennin (794–864), the Persian historian Rashid al-Din Hamadani (1247–1318), the Korean official Choe Bu (1454–1504), and the Italian missionary Matteo Ricci (1552–1610).[3][4]

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search