Back Ісьляндзкае імя BE-X-OLD Nom islandès Catalan Islandské jméno Czech Isländischer Personenname German Islanda nomo Esperanto Nombre islandés Spanish Islandi isikunimed Estonian Nom islandais French Antroponimia islandesa Galician שמות איסלנדיים HE

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

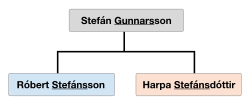

Icelandic names are names used by people from Iceland. Icelandic surnames are different from most other naming systems in the modern Western world in that they are patronymic or occasionally matronymic: they indicate the father (or mother) of the child and not the historic family lineage. Iceland shares a common cultural heritage with the Scandinavian countries of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Unlike these countries, Icelanders have continued to use their traditional name system, which was formerly used in most of Northern Europe.[a] The Icelandic system is thus not based on family names (although some people do have family names and might use both systems). Generally, with few exceptions, a person's last name indicates the first name of their father (patronymic) or in some cases mother (matronymic) in the genitive, followed by -son ("son") or -dóttir ("daughter").

Some family names do exist in Iceland, most commonly adaptations from last names Icelanders took up when living abroad, usually in Denmark. Notable Icelanders who have an inherited family name include former prime minister Geir Haarde, football star Eiður Smári Guðjohnsen, entrepreneur Magnús Scheving, film director Baltasar Kormákur Samper, and actress Anita Briem. Before 1925, it was lawful to adopt new family names; one Icelander to do so was the Nobel Prize-winning author Halldór Laxness, while another author, Einar Hjörleifsson and his brothers all chose the family name "Kvaran". Since 1925, one cannot adopt a family name unless one explicitly has a legal right to do so through inheritance.[4][5]

First names not previously used in Iceland must be approved by the Icelandic Naming Committee before being used.[6] The criterion for acceptance of names is whether they can be easily incorporated into the Icelandic language. With some exceptions, they must contain only letters found in the Icelandic alphabet (including þ and ð), and it must be possible to decline the name according to the language's grammatical case system, which in practice means that a genitive form can be constructed in accordance with Icelandic rules. Names considered to be gender-nonconforming have historically not been allowed; however, in January 2013, a 15-year-old girl named Blær (a masculine noun in Icelandic) was allowed to keep this name in a court decision that overruled an initial rejection by the naming committee.[7] Her mother Björk Eiðsdóttir did not realize at the time that Blær was considered masculine; she had read a novel by Halldór Laxness, The Fish Can Sing (1957), that had an admirable female character named Blær, meaning "light breeze", and had decided that if she had a daughter, she would name her Blær.[8]

In 2019, the laws governing names were changed. First names are no longer restricted by gender. Moreover, Icelanders who are officially registered as non-binary are permitted to use the patro/matronymic suffix -bur ("child of") instead of -son or -dóttir.[9]

- ^ "Fornavne, mellemnavne og efternavne". Ankestyrelsen. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Surnames with the suffix -son or -dotter". Swedish Patent and Registration Office. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Nimilaki Archived 10 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine (694/1985) § 26. Retrieved 3-11-2008. (in Finnish)

- ^ "Personal Names Act, No. 45 of 17th May 1996". Ministry of the Justice. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ grapevine.is (10 July 2014). "So What's This Naming Law I Keep Hearing About? - The Reykjavik Grapevine". Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ^ "Naming Committee accepts Asía, rejects Magnus". Morgunblaðið online. 12 September 2006. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012 – via Iceland Review Online.

- ^ Blaer Bjarkardottir, Icelandic Teen, Wins Right To Use Her Given Name Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Huffington Post, 31 January 2013

- ^ "Where Everybody Knows Your Name, Because It's Illegal". The Stateless Man. 28 January 2013. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013.

- ^ Kyzer, Larissa (22 June 2019). "Icelandic names will no longer be gendered". Iceland Review. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search