Back لولب رحمي Arabic Унутрыматачная спіраль Byelorussian Унутрамацічная сьпіраль BE-X-OLD Dispositiu intrauterí Catalan Nitroděložní tělísko Czech Spiral (prævention) Danish Intrauterinpessar German Enutera pesario Esperanto Dispositivo intrauterino Spanish Spiraal (kontratseptiiv) Estonian

| Intrauterine device | |

|---|---|

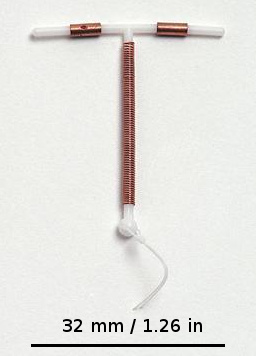

Copper IUD (Paragard T 380A) | |

| Background | |

| Type | Intrauterine |

| First use | 1800s[1] |

| Synonyms | Intrauterine system |

| Failure rates (first year) | |

| Perfect use | <1%[2] |

| Typical use | <1%[2] |

| Usage | |

| User reminders | None |

| Advantages and disadvantages | |

| STI protection | No |

| Periods | Depends on the type |

| Weight | No effect |

An intrauterine device (IUD), also known as an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD or ICD) or coil,[3] is a small, often T-shaped birth control device that is inserted into the uterus to prevent pregnancy. IUDs are a form of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC).[4]

The use of IUDs as a form of birth control dates from the 1800s.[1] A previous model known as the Dalkon shield was associated with an increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). However, current models do not affect PID risk in women without sexually transmitted infections during the time of insertion.[5]

Although copper IUDs may increase menstrual bleeding and result in painful cramps,[6] hormonal IUDs may reduce menstrual bleeding or stop menstruation altogether.[7] However, women can have daily spotting for several months after insertion, and it can take up to three months for there to be a 90% decrease in bleeding with hormonal IUDs.[8] Cramping can be treated with NSAIDs.[9] More serious potential complications include expulsion (2–5%), uterus perforation(less than 0.7%), and bladder perforation.[7][10][9] Levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs) may be associated with psychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, particularly in younger users, though evidence remains mixed and further research is needed.[11] IUDs do not affect breastfeeding and can be inserted immediately after delivery.[7] They may also be used immediately after an abortion.[12][13]

IUDs are safe and effective in adolescents as well as those who have not previously had children.[14][15] Once an IUD is removed, even after long-term use, fertility returns to normal rapidly.[16] Copper devices have a failure rate of about 0.8%, while hormonal (levonorgestrel) devices fail about 0.2% of the time within the first year of use.[17] In comparison, male sterilization and male condoms have a failure rate of about 0.15% and 15%, respectively.[18] Copper IUDs can also be used as emergency contraception within five days of unprotected sex.[19]

Globally, 14.3% of married or partnered women aged 15–49 use intrauterine contraception, with over 80% of users concentrated in Asia, particularly China. Among birth control methods, IUDs, along with other contraceptive implants, result in the greatest satisfaction among users.[14]

- ^ a b Callahan T, Caughey AB (2013). Blueprints Obstetrics and Gynecology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-4511-1702-8.

- ^ a b "ParaGard (copper IUD)". Drugs.com. 7 September 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ "IUD (intrauterine device)". Contraception guide. NHS Choices. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

the intrauterine device, or IUD (sometimes called a coil)

- ^ Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Buckel C, Madden T, Allsworth JE, et al. (May 2012). "Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception". The New England Journal of Medicine. 366 (21): 1998–2007. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110855. PMID 22621627. S2CID 16812353.

- ^ Sonfield A (Fall 2007). "Popularity Disparity: Attitudes About the IUD in Europe and the United States". Guttmacher Policy Review. Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ Grimes DA, Nelson TJ, Guest F, Kowal D (2007). Hatcher RA (ed.). "Intrauterine Devices (IUDs)". Contraceptive Technology (19th ed.).

- ^ a b c Gabbe S (2012). Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 527. ISBN 978-1-4557-3395-8.

- ^ Shoupe D (2011). Contraception. John Wiley & Sons. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-4443-4263-5.

- ^ a b Marnach ML, Long ME, Casey PM (March 2013). "Current issues in contraception". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 88 (3): 295–299. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.01.007. PMID 23489454.

- ^ Liu G, Li F, Ao M, Huang G (16 August 2021). "Intrauterine devices migrated into the bladder: two case reports and literature review". BMC Women's Health. 21 (1): 301. doi:10.1186/s12905-021-01443-w. ISSN 1472-6874. PMC 8365895. PMID 34399735.

- ^ Elsayed M, Dardeer KT, Khehra N, Padda I, Graf H, Soliman A, et al. (3 July 2023). "The potential association between psychiatric symptoms and the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs): A systematic review". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 24 (6): 457–475. doi:10.1080/15622975.2022.2145354. ISSN 1562-2975. PMID 36426589.

- ^ Steenland MW, Tepper NK, Curtis KM, Kapp N (November 2011). "Intrauterine contraceptive insertion postabortion: a systematic review". Contraception. 84 (5): 447–464. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.03.007. PMID 22018119.

- ^ Roe AH, Bartz D (January 2019). "Society of Family Planning clinical recommendations: contraception after surgical abortion". Contraception. 99 (1): 2–9. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.08.016. PMID 30195718.

- ^ a b "Committee opinion no. 539: adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 120 (4): 983–988. October 2012. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182723b7d. PMID 22996129. S2CID 35516759.

- ^ Black K, Lotke P, Buhling KJ, Zite NB, et al. (Intrauterine contraception for Nulliparous women: Translating Research into Action (INTRA), group) (October 2012). "A review of barriers and myths preventing the more widespread use of intrauterine contraception in nulliparous women". The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 17 (5): 340–350. doi:10.3109/13625187.2012.700744. PMC 4950459. PMID 22834648.

- ^ Hurd T, Falcone WW, eds. (2007). Clinical reproductive medicine and surgery. Philadelphia: Mosby. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-323-03309-1.

- ^ Hurt KJ, Guile MW, Bienstock JL, Fox HE, Wallach EE, eds. (28 March 2012). The Johns Hopkins manual of gynecology and obstetrics (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-60547-433-5.

- ^ "Contraception Editorial January 2008: Reducing Unintended Pregnancy in the United States". www.arhp.org. January 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Emergency Contraception - ACOG". www.acog.org. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search