Back الرق في الإسلام Arabic ইসলাম ধর্মে দাসত্ব Bengali/Bangla Caethwasiaeth ac Islam Welsh Sklaverei im Islam German بردهداری در اسلام Persian Orjuus islamilaisessa maailmassa Finnish Traite arabo-musulmane French עבדות באסלאם HE गुलामी पर इस्लाम के विचार Hindi Ստրկությունը իսլամում Armenian

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

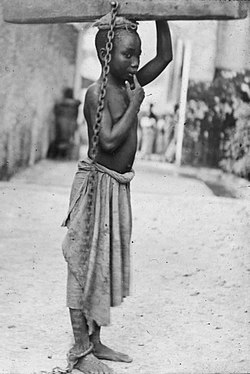

Islamic views on slavery represent a complex and multifaceted body of Islamic thought,[1][2] with various Islamic groups and thinkers espousing views on the matter which have been radically different throughout history.[3] Slavery existed in pre-Islamic Arabia, and Muhammad himself was a slave owner who never expressed any intention of abolishing the practice.[4][5][6] However, his teachings emphasized improving the condition of slaves, and he exhorted his followers to treat them more humanely. In consequence, slavery was recognised as a valid institution in traditional Islamic jurisprudence, subject to certain conditions and rules.[1][7][8]

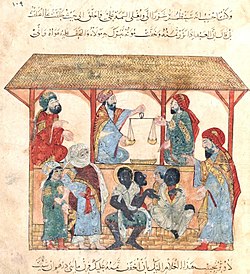

Early Islamic dogma allowed enslavement of other human beings with the exception free members of Islamic society, including non-Muslims (dhimmis), and set out to regulate and improve the conditions of human bondage. The sharīʿah (divine law) regarded as legal slaves only those non-Muslims who were imprisoned or bought beyond the borders of Islamic rule, or the sons and daughters of slaves already in captivity.[8] It also allowed men to have sexual relationships with slave women without the requirement of "nikah".[9] In later classical Islamic law, the topic of slavery is covered at great length.[3] Slaves, be they Muslim or those of any other religion, were equal to their fellow practitioners in religious issues.[10] However, the consent of a slave for sex, for withdrawal before ejaculation (azl) or to marry her off to someone else, was historically not considered necessary.[11] In theory, slavery in Islamic law does not have a racial or color component, although this has not always been the case in practice.[12] Slaves played various social and economic roles, from domestic worker to high-ranking positions in the government. Moreover, slaves were widely employed in irrigation, mining, pastoralism, and the army.[13] In some cases, the treatment of slaves was so harsh that it led to uprisings, such as the Zanj Rebellion.[14][15][16] Slaves and concubines are considered as possessions in Sharia;[17] masters may sell, bequeath, give away, pledge, share, hire out or compel them to earn money.[18][19][20]

The Muslim slave trade was most active in West Asia, Eastern Europe, and Sub-Saharan Africa.[22] After the Trans-Atlantic slave trade had been suppressed, the ancient Trans-Saharan slave trade, the Indian Ocean slave trade and the Red Sea slave trade continued to traffic slaves from the African continent to the Middle East.[22] Estimates vary widely, with some suggesting up to 17 million slaves to the coast of the Indian Ocean, the Middle East, and North Africa.[23] Abolitionist movements began to grow during the 19th century, prompted by both Muslim reformers and diplomatic pressure from Britain. The first Muslim country to prohibit slavery was Tunisia, in 1846.[24] During the 19th and early 20th centuries all large Muslim countries, whether independent or under colonial rule, banned the slave trade and/or slavery. The Dutch East Indies abolished slavery in 1860 but effectively ended in 1910, while British India abolished slavery in 1862.[25] The Ottoman Empire banned the African slave trade in 1857 and the Circassian slave trade in 1908,[26] while Egypt abolished slavery in 1895, Afghanistan in 1921 and Persia in 1929.[27] In some Muslim countries in the Arabian peninsula and Africa, slavery was abolished in the second half of the 20th century: 1962 in Saudi Arabia and Yemen, Oman in 1970, Mauritania in 1981.[28] However, slavery has been documented in recent years, despite its illegality, in Muslim-majority countries in Africa including Chad, Mauritania, Niger, Mali, and Sudan.[29][30]

Some early converts to Islam were former slaves. One notable example is Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi, who is noted for being the first Muezzin.[31] In modern times, various Muslim organizations reject the permissibility of slavery and it has since been abolished by all Muslim majority countries due to social and economic pressure from the western world.[32][33] Although, many modern Muslims see slavery as contrary to Islamic principles of justice and equality,[34][35] there have been many Islamic extremist groups and terrorist organizations who have periodically revived the practice of slavery.[36]

- ^ a b Brockopp, Jonathan E., “Slaves and Slavery”, in: Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān, General Editor: Jane Dammen McAuliffe, Georgetown University, Washington DC.

- ^ Brunschvig, R., “ʿAbd”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs.

- ^ a b Lewis 1994, Ch.1 Archived 2001-04-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gordon 1989.

- ^ Levy, Reuben (2000). "Slavery in Islam". The Social Structure of Islam. NY: Routledge. pp. 73–90. ISBN 978-0415209106.

- ^ https://www.brandeis.edu/projects/fse/muslim/slavery.html

- ^ Brunschvig. 'Abd; Encyclopedia of Islam

- ^ a b Dror Ze’evi (2009). "Slavery". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2017-02-23. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ^ https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/the-truth-about-muslims-and-sex-slavery-according-to-the-quran-rather-than-isis-or-islamophobes-a6875446.html%3Famp&ved=2ahUKEwiFyYubwqvpAhVrThUIHX-ZDxAQFjAEegQIBBAB&usg=AOvVaw1G3Py-_GoYBqsPdxjD7ad_&cf=1

- ^ See: Martin (2005), pp.150 and 151; Clarence-Smith (2006), p.2

- ^ Ali, Kecia (20 January 2017). "Concubinage and Consent". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 49 (1). Cambridge University Press (CUP): 148–152. doi:10.1017/s0020743816001203. ISSN 0020-7438.

- ^ Bernard Lewis, Race and Color in Islam, Harper and Row, 1970, quote on page 38. The brackets are displayed by Lewis.

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Cairo of the Mamluks: A History of Architecture and Its Culture. New York: Macmillan, 2008.

- ^ Clarence-Smith (2006), pp.2-5

- ^ William D. Phillips (1985). Slavery from Roman times to the early transatlantic trade. Manchester University Press. p. 76. ISBN 0-7190-1825-0.

- ^ "Development of History and Hadith Collections". www.al-islam.org. 2013-11-12. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ a b Jonathan E. Brockopp (2000), Early Mālikī Law: Ibn ʻAbd Al-Ḥakam and His Major Compendium of Jurisprudence, Brill, ISBN 978-9004116283, pp. 131

- ^ Levy (1957) p. 77

- ^ "Sahih Bukhari | Chapter: 48 | Manumission of Slaves". ahadith.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ "BBC - Religions - Islam: Slavery in Islam". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ Levy (1957) p. 77

- ^ a b La Rue, George M. (17 August 2023). "Indian Ocean and Middle Eastern Slave Trades". Oxford Bibliographies Online. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199846733-0051. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Focus on the slave trade". May 25, 2017. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Montana, Ismael (2013). The Abolition of Slavery in Ottoman Tunisia. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813044828.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Erdem, Y. Hakan (1996). Slavery in the Ottoman Empire and its Demise, 1800-1909. Macmillan. pp. 95–151. ISBN 0333643232.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, pp. 110–116.

- ^ Martin A. Klein (2002), Historical Dictionary of Slavery and Abolition, Page xxii, ISBN 0810841029

- ^ Segal, page 206. See later in article.

- ^ Segal, page 222. See later in article.

- ^ Robinson, David (2004-01-12). Muslim Societies in African History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53366-9.

- ^ "University of Minnesota Human Rights Library". 2018-11-03. Archived from the original on 2018-11-03. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Cortese 2013.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

eoqwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ali 2006, pp. 53–54: "...the practical limitations of the Prophet’s mission meant that acquiescence to slave ownership was necessary, though distasteful, but meant to be temporary."

- ^ "ISIS and Their Use of Slavery". International Centre for Counter-Terrorism - ICCT. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search