Back Maad a Sinig Ama Diouf Gnilane Faye Diouf French Ама Діуф Гнілане Файє Ukrainian Maad a Sinig Ama Juuf Njeelane Faye Juuf Wolof

| Maad a Sinig Ama Joof Gnilane Faye Joof | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

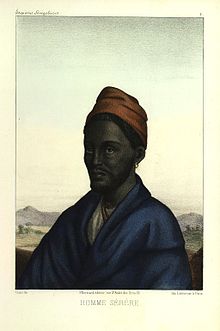

Maad a Sinig Ama Joof Gnilane Faye Joof. King of Sine. Reigned : c. 1825 to 1853. From The Royal House of Semou Njekeh Joof. He is one of few pre-colonial Senegambian kings imortalised in a portrait. Watercolor Sketches of David Boilat in Esquisses sénégalaises 1853, original portrait taken in 1850 when Boilat visited Joal.[1][2]

| |||||

| Reign | 1825–1853 | ||||

| Coronation | c. 1825 Crowned at Diakhao, Kingdom of Sine, present-day | ||||

| Predecessor | Maad a Sinig Njaak Wagam Gnilane Faye (Maad a Sinig). Ama Kumba Mbodj (regent). | ||||

| Heir-apparent | Maad a Sinig Kumba Ndoffene Famak Joof | ||||

| Born | Diakhao, Kingdom of Sine, present-day | ||||

| |||||

| House | The Royal House of Semou Njekeh Joof founded by Maad Semou Njekeh Joof in the 18th century | ||||

| Father | Sandigui N'Diob Niokhobai Joof | ||||

| Mother | Lingeer Gnilane Faye | ||||

| Religion | Serer religion | ||||

Maad a Sinig Ama Joof Gnilane Faye Joof (many variations of his name: Ama Joof, Amat Diouf, Amajuf Ñilan Fay Juf, Amadiouf Diouf, Ama Diouf Faye, Ama Diouf Gnilane Faye Diouf, Ramat Dhiouf, etc.) was a king of Sine now part of present-day Senegal. He reigned from c. 1825 to 1853.[3][4] He was fluent in several languages.[5] He came from The Royal House of Semou Njekeh Joof (the third and last royal house founded by the Joof family of Sine and Saloum in the 18th century). Maad a Sinig (variations: Mad Sinig etc.) means king of Sine in the Serer-Sine language. The term Bur Sine (variations: Buur Sine or Bour Sine) is also used interchangeably with the proper title Maad a Sinig or Mad a Sinig. They both mean king Sine. Bour Sine is usually used by the Wolof people when referring to the Serer kings of Sine. The Serer people generally used the term Maad a Sinig or Mad a Sinig when referring to their kings.[6][7]

- ^ Boilat, David (The Father David Boilat), who was in Joal in 1850 met King Ama Diouf whom he portrays in his work Esquisses sénégalaises which was completed in 1853. That was three years before the death of the King. See: Boilat: Esquisses sénégalaises, Bertrand, 1853, p. 145

- ^ Diouf, Niokhobaye, Chronique du royaume du Sine. Suivie de Notes sur les traditions orales et les sources écrites concernant le royaume du Sine par Charles Becker et Victor Martin. Bulletin de l'IFAN, Tome 34, Série B, n° 4, 1972. pp 772-774 (pp 47-49)

- ^ Klein, Martin A. Islam and Imperialism in Senegal Sine-Saloum, 1847–1914. Edinburgh University Press (1968), pp7, xv.

- ^ Saint-Martin, Yves-Jean, Le Sénégal sous le second empire, KARTHALA Editions, 1989, ISBN 2865372014, p48

- ^ Boilat, David, Esquisses sénégalaises

- ^ Oliver, Roland, Fage, John Donnelly, Sanderson, G. N. The Cambridge History of Africa, Cambridge University Press, 1985, p. 214 ISBN 0521228034

- ^ Diouf, Marcel Mahawa, Lances mâles : Léopold Sédar Senghor et les traditions sérères, Centre d'études linguistiques et historiques par tradition orale, Niamey, 1996, p. 54

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search