Marine viruses are defined by their habitat as viruses that are found in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. Viruses are small infectious agents that can only replicate inside the living cells of a host organism, because they need the replication machinery of the host to do so.[4] They can infect all types of life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.[5]

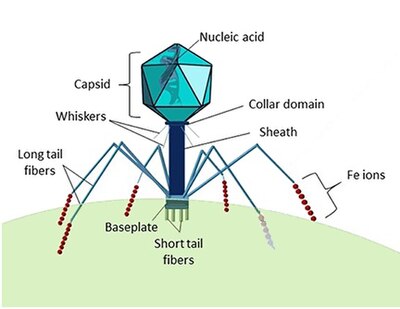

When not inside a cell or in the process of infecting a cell, viruses exist in the form of independent particles called virions. A virion contains a genome (a long molecule that carries genetic information in the form of either DNA or RNA) surrounded by a capsid (a protein coat protecting the genetic material). The shapes of these virus particles range from simple helical and icosahedral forms for some virus species to more complex structures for others. Most virus species have virions that are too small to be seen with an optical microscope. The average virion is about one one-hundredth the linear size of the average bacterium.

A teaspoon of seawater typically contains about fifty million viruses.[6] Most of these viruses are bacteriophages which infect and destroy marine bacteria and control the growth of phytoplankton at the base of the marine food web. Bacteriophages are harmless to plants and animals but are essential to the regulation of marine ecosystems. They supply key mechanisms for recycling ocean carbon and nutrients. In a process known as the viral shunt, organic molecules released from dead bacterial cells stimulate fresh bacterial and algal growth. In particular, the breaking down of bacteria by viruses (lysis) has been shown to enhance nitrogen cycling and stimulate phytoplankton growth. Viral activity also affects the biological pump, the process which sequesters carbon in the deep ocean. By increasing the amount of respiration in the oceans, viruses are indirectly responsible for reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by approximately 3 gigatonnes of carbon per year.

Marine microorganisms make up about 70% of the total marine biomass. It is estimated marine viruses kill 20% of the microorganism biomass every day. Viruses are the main agents responsible for the rapid destruction of harmful algal blooms which often kill other marine life. The number of viruses in the oceans decreases further offshore and deeper into the water, where there are fewer host organisms. Viruses are an important natural means of transferring genes between different species, which increases genetic diversity and drives evolution. It is thought viruses played a central role in early evolution before the diversification of bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes, at the time of the last universal common ancestor of life on Earth. Viruses are still one of the largest areas of unexplored genetic diversity on Earth.

| Part of a series of overviews on |

| Marine life |

|---|

|

- ^ Bonnain C, Breitbart M, Buck K (2016). "The ferrojan horse hypothesis: iron-virus interactions in the ocean". Frontiers in Marine Science. 3: 82. doi:10.3389/fmars.2016.00082. S2CID 2917222.

- ^ These Tiny Organisms Have Some Really Weird Shapes, National Geographic, 12 November 2016.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Shors2008was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Brussaard CP, Baudoux AC, Rodríguez-Valera F (2016). Stal LJ, Cretoiu MS (eds.). Marine Viruses. Springer International Publishing. pp. 155–183. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-33000-6_5. ISBN 9783319329987.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Koonin EV, Senkevich TG, Dolja VV (2006). "The ancient Virus World and evolution of cells". Biology Direct. 1: 29. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-1-29. PMC 1594570. PMID 16984643.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License.

Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License.

- ^ Suttle C (2005). "Viruses in the sea". Nature. 437 (7057): 356–361. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..356S. doi:10.1038/nature04160. PMID 16163346. S2CID 4370363.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search