Back ميلانين Arabic Melanina AST Melanin Azerbaijani Мэлянін BE-X-OLD Меланин Bulgarian মেলানিন Bengali/Bangla Melanin BS Melanina Catalan Melanin Czech Melanin Danish

| Melanin | |

|---|---|

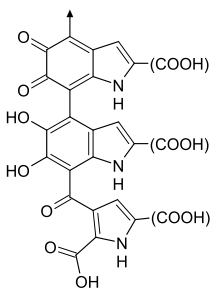

One possible structure of Eumelanin | |

| Material type | Heterogeneous biopolymer |

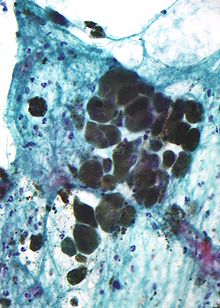

Melanin (/ˈmɛlənɪn/ ; from Ancient Greek μέλας (mélas) 'black, dark') is a family of biomolecules organized as oligomers or polymers, which among other functions provide the pigments of many organisms.[1] Melanin pigments are produced in a specialized group of cells known as melanocytes.

There are five basic types of melanin: eumelanin, pheomelanin, neuromelanin, allomelanin and pyomelanin.[2] Eumelanin is produced through a multistage chemical process known as melanogenesis, where the oxidation of the amino acid tyrosine is followed by polymerization. Eumelanin is the most common type. Pheomelanin, which is produced when melanocytes are malfunctioning due to derivation of the gene to its recessive format, is a cysteine-derivative that contains polybenzothiazine portions that are largely responsible for the red or yellow tint given to some skin or hair colors. Neuromelanin is found in the brain. Research has been undertaken to investigate its efficacy in treating neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson's.[3] Allomelanin and pyomelanin are two types of nitrogen-free melanin.

In the human skin, melanogenesis is initiated by exposure to UV radiation, causing the skin to darken. Eumelanin is an effective absorbent of light; the pigment is able to dissipate over 99.9% of absorbed UV radiation.[4] Because of this property, eumelanin is thought to protect skin cells from UVA and UVB radiation damage, reducing the risk of folate depletion and dermal degradation. Exposure to UV radiation is associated with increased risk of malignant melanoma, a cancer of melanocytes (melanin cells). Studies have shown a lower incidence for skin cancer in individuals with more concentrated melanin, i.e. darker skin tone.[5]

- ^ Casadevall, Arturo (2018). "Melanin triggers antifungal defences". Nature. 555 (7696): 319–320. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..319C. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-02370-x. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 29542711. S2CID 3832753.

- ^ Cao, Wei; Zhou, Xuhao; McCallum, Naneki C.; Hu, Ziying; Ni, Qing Zhe; Kapoor, Utkarsh; Heil, Christian M.; Cay, Kristine S.; Zand, Tara; Mantanona, Alex J.; Jayaraman, Arthi (9 February 2021). "Unraveling the Structure and Function of Melanin through Synthesis". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 143 (7): 2622–2637. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c12322. hdl:1854/LU-8699336. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 33560127. S2CID 231872855.

- ^ Haining, Robert L.; Achat-Mendes, Cindy (March 2017). "Neuromelanin, one of the most overlooked molecules in modern medicine, is not a spectator". Neural Regeneration Research. 12 (3): 372–375. doi:10.4103/1673-5374.202928. PMC 5399705. PMID 28469642.

- ^ Meredith P, Riesz J (2004). "Radiative relaxation quantum yields for synthetic eumelanin". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 79 (2): 211–6. arXiv:cond-mat/0312277. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2004.tb00012.x. PMID 15068035. S2CID 222101966.

- ^ Brenner M, Hearing VJ (2008). "The protective role of melanin against UV damage in human skin". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 84 (3): 539–49. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00226.x. PMC 2671032. PMID 18435612.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search