Back أوليفر وندل هولمز، الابن Arabic اوليفر وندل هولمز ARZ اولیور وندل هو.ام.جی. AZB Oliver Wendell Holmes mladší Czech Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. German Oliver Wendell Holmes (jurista) Spanish Oliver Wendell Holmes (nuorempi) Finnish Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. French אוליבר ונדל הולמס הבן HE Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. ID

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. | |

|---|---|

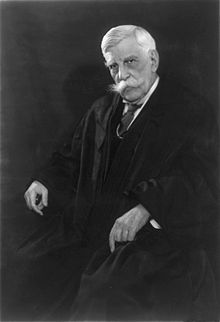

Justice Holmes c. 1930 | |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office December 8, 1902 – January 12, 1932[1] | |

| Nominated by | Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Horace Gray |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin N. Cardozo |

| Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court | |

| In office August 2, 1899 – December 4, 1902 | |

| Nominated by | Murray Crane |

| Preceded by | Walbridge Field |

| Succeeded by | Marcus Knowlton |

| Associate Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court | |

| In office December 15, 1882 – August 2, 1899 | |

| Nominated by | John Long |

| Preceded by | Otis Lord |

| Succeeded by | William Loring |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 8, 1841 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | March 6, 1935 (aged 93) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Fanny Bowditch Dixwell

(m. 1873; died 1929) |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Edward Jackson Holmes (brother) Amelia Jackson Holmes (sister) Judge Charles Jackson (grandfather) Abiel Holmes (grandfather) Jonathan Jackson (great-grandfather) Edward J. Holmes (nephew) |

| Education | Harvard University (AB, LLB) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Brevet Colonel |

| Unit | 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry |

| Battles/wars | |

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (March 8, 1841 – March 6, 1935) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1902 to 1932.[A] Holmes is one of the most widely cited Supreme Court justices and among the most influential American judges in history, noted for his long service, pithy opinions—particularly those on civil liberties and American constitutional democracy—and deference to the decisions of elected legislatures. Holmes retired from the court at the age of 90, an unbeaten record for oldest justice on the Supreme Court.[B] He previously served as a Brevet Colonel in the American Civil War, in which he was wounded three times, as an associate justice and chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and as Weld Professor of Law at his alma mater, Harvard Law School. His positions, distinctive personality, and writing style made him a popular figure, especially with American progressives.[2]

During his tenure on the U.S. Supreme Court, to which he was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1902, he supported the constitutionality of state economic regulation and came to advocate broad freedom of speech under the First Amendment, after, in Schenck v. United States (1919), having upheld for a unanimous court criminal sanctions against draft protestors with the memorable maxim that "free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic" and formulating the groundbreaking "clear and present danger" test.[3] Later that same year, in his famous dissent in Abrams v. United States (1919), he wrote that "the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market ... That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment." He added that "we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death ..."[4]

He was one of only a handful of justices known as a scholar; The Journal of Legal Studies has identified Holmes as the third-most-cited American legal scholar of the 20th century.[5] Holmes was a legal realist, as summed up in his maxim, "The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience",[6] and a moral skeptic[7] opposed to the doctrine of natural law. His jurisprudence and academic writing influenced much subsequent American legal thinking, including the judicial consensus upholding New Deal regulatory law and the influential American schools of pragmatism, critical legal studies, and law and economics.[citation needed]

- ^ "Justices 1789 to Present". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ Louis Menand, ed., Pragmatism: A Reader. New York: Vintage Books, 1997, p. xxix.

- ^ Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47, 52 (1919).

- ^ Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616, 630 (1919).

- ^ Shapiro, Fred R. (2000). "The Most-Cited Legal Scholars". Journal of Legal Studies. 29 (1): 409–426. doi:10.1086/468080. S2CID 143676627.

- ^ Holmes, Oliver Wendell Jr. (1881). The Common Law. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 3. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Alschuler, Albert W., Law without Values.

Cite error: There are <ref group=upper-alpha> tags or {{efn-ua}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=upper-alpha}} template or {{notelist-ua}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search