Back بوابة:علم الفيروسات Arabic درگاه:ویروس Persian Portail:Virologie French Portal:Virus ID Portal:Vírus Portuguese ද්වාරය:වෛරස Singhalese باب:وائرسز Urdu Portal:病毒 Chinese

The Viruses Portal

Welcome!

Viruses are small infectious agents that can replicate only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all forms of life, including animals, plants, fungi, bacteria and archaea. They are found in almost every ecosystem on Earth and are the most abundant type of biological entity, with millions of different types, although only about 6,000 viruses have been described in detail. Some viruses cause disease in humans, and others are responsible for economically important diseases of livestock and crops.

Virus particles (known as virions) consist of genetic material, which can be either DNA or RNA, wrapped in a protein coat called the capsid; some viruses also have an outer lipid envelope. The capsid can take simple helical or icosahedral forms, or more complex structures. The average virus is about 1/100 the size of the average bacterium, and most are too small to be seen directly with an optical microscope.

The origins of viruses are unclear: some may have evolved from plasmids, others from bacteria. Viruses are sometimes considered to be a life form, because they carry genetic material, reproduce and evolve through natural selection. However they lack key characteristics (such as cell structure) that are generally considered necessary to count as life. Because they possess some but not all such qualities, viruses have been described as "organisms at the edge of life".

Selected disease

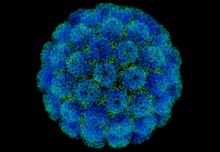

Polio, also called poliomyelitis or infantile paralysis, was one of the most feared childhood diseases of the 20th century. Poliovirus, the causative agent, only naturally infects humans and spreads via the faecal–oral route. Most infections cause no or minor symptoms. In around 1% of cases, the virus enters the central nervous system, causing aseptic meningitis. There it can preferentially infect and destroy motor neurons, leading in 0.1–0.5% of cases to muscle weakness and acute flaccid paralysis. Spinal polio accounts for nearly 80% of paralytic cases, with asymmetric paralysis of the legs being typical; in a quarter of these cases permanent severe disability results. Bulbar involvement is rare, but in severe cases the virus can prevent breathing by affecting the phrenic nerve, so that patients require mechanical ventilation with an iron lung or similar device.

Depictions in ancient art show that the disease has existed for thousands of years. The virus was an endemic pathogen until the 1880s, when major epidemics began to occur in Europe and later the United States. Polio vaccines were developed in the 1950s and a global eradication campaign started in 1988. The annual incidence of wild-type disease fell from many hundreds of thousands to 22 in 2017, but has since resurged to a few hundreds.

Selected image

1802 cartoon of Edward Jenner administering cowpox vaccine against smallpox, satirising contemporary fears about vaccination.

Credit: James Gillray (12 June 1802)

In the news

26 February: In the ongoing pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), more than 110 million confirmed cases, including 2.5 million deaths, have been documented globally since the outbreak began in December 2019. WHO

18 February: Seven asymptomatic cases of avian influenza A subtype H5N8, the first documented H5N8 cases in humans, are reported in Astrakhan Oblast, Russia, after more than 100,0000 hens died on a poultry farm in December. WHO

14 February: Seven cases of Ebola virus disease are reported in Gouécké, south-east Guinea. WHO

7 February: A case of Ebola virus disease is detected in North Kivu Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. WHO

4 February: An outbreak of Rift Valley fever is ongoing in Kenya, with 32 human cases, including 11 deaths, since the outbreak started in November. WHO

21 November: The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gives emergency-use authorisation to casirivimab/imdevimab, a combination monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy for non-hospitalised people twelve years and over with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, after granting emergency-use authorisation to the single mAb bamlanivimab earlier in the month. FDA 1, 2

18 November: The outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Équateur Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo, which started in June, has been declared over; a total of 130 cases were recorded, with 55 deaths. UN

Selected article

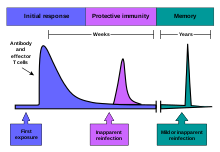

The immune system is a system of structures and processes within an organism that protects against disease. It must detect a wide variety of pathogens – from viruses to parasitic worms – distinguish them from the organism's own healthy tissue, and neutralise them. Simple unicellular organisms such as bacteria have enzymes that protect against bacteriophage infections. Other basic immune mechanisms, including phagocytosis, antimicrobial peptides called defensins, and the complement system, evolved in ancient eukaryotes and are found in plants and invertebrates.

Humans and most other vertebrates have more sophisticated defence mechanisms, including the ability to adapt over time to recognise specific pathogens more efficiently. Adaptive immunity creates immunological memory after an initial response to a specific pathogen, leading to an enhanced response to subsequent encounters with that same pathogen. This process of acquired immunity is the basis of vaccination. Viruses and other pathogens can rapidly evolve to evade immune detection, and some viruses, notably HIV, cause the immune system to function less effectively.

Selected outbreak

The 2009 flu pandemic was an influenza pandemic first recognised in Mexico City in March 2009 and declared over in August 2010. It involved a novel strain of H1N1 influenza virus with genes from five different viruses, which resulted when a previous triple reassortment of avian, swine and human influenza viruses further combined with a Eurasian swine influenza virus, leading to the term "swine flu" being used for the pandemic. It was the second pandemic to involve an H1N1 strain, the first being the 1918 "Spanish flu" pandemic.

The global infection rate was estimated as 11–21%. This pandemic strain was less lethal than previous ones, killing about 0.01–0.03% of those infected, compared with 2–3% for Spanish flu. Most experts agree that at least 284,500 people died, mainly in Africa and Southeast Asia – comparable with the normal seasonal influenza fatalities of 290,000–650,000 – leading to claims that the World Health Organization had exaggerated the danger.

Selected quotation

| “ | ...in a flash I had understood: what caused my clear spots was, in fact, an invisible microbe, a filterable virus, but a virus parasitic on bacteria. | ” |

—Félix d'Herelle on the discovery of bacteriophages

Recommended articles

Viruses & Subviral agents: bat virome • elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus • HIV • introduction to viruses![]() • Playa de Oro virus • poliovirus • prion • rotavirus

• Playa de Oro virus • poliovirus • prion • rotavirus![]() • virus

• virus![]()

Diseases: colony collapse disorder • common cold • croup • dengue fever![]() • gastroenteritis • Guillain–Barré syndrome • hepatitis B • hepatitis C • hepatitis E • herpes simplex • HIV/AIDS • influenza

• gastroenteritis • Guillain–Barré syndrome • hepatitis B • hepatitis C • hepatitis E • herpes simplex • HIV/AIDS • influenza![]() • meningitis

• meningitis![]() • myxomatosis • polio

• myxomatosis • polio![]() • pneumonia • shingles • smallpox

• pneumonia • shingles • smallpox

Epidemiology & Interventions: 2007 Bernard Matthews H5N1 outbreak • Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations • Disease X • 2009 flu pandemic • HIV/AIDS in Malawi • polio vaccine • Spanish flu • West African Ebola virus epidemic

Virus–Host interactions: antibody • host • immune system![]() • parasitism • RNA interference

• parasitism • RNA interference![]()

Methodology: metagenomics

Social & Media: And the Band Played On • Contagion • "Flu Season" • Frank's Cock![]() • Race Against Time: Searching for Hope in AIDS-Ravaged Africa

• Race Against Time: Searching for Hope in AIDS-Ravaged Africa![]() • social history of viruses

• social history of viruses![]() • "Steve Burdick" • "The Time Is Now" • "What Lies Below"

• "Steve Burdick" • "The Time Is Now" • "What Lies Below"

People: Brownie Mary • Macfarlane Burnet![]() • Bobbi Campbell • Aniru Conteh • people with hepatitis C

• Bobbi Campbell • Aniru Conteh • people with hepatitis C![]() • HIV-positive people

• HIV-positive people![]() • Bette Korber • Henrietta Lacks • Linda Laubenstein • Barbara McClintock

• Bette Korber • Henrietta Lacks • Linda Laubenstein • Barbara McClintock![]() • poliomyelitis survivors

• poliomyelitis survivors![]() • Joseph Sonnabend • Eli Todd • Ryan White

• Joseph Sonnabend • Eli Todd • Ryan White![]()

Selected virus

Henipaviruses are a genus of RNA viruses in the Paramyxoviridae family. The variably shaped, 40–600 nm diameter, enveloped capsid contains a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome of 18.2 kb, with six genes. The cellular receptor is in the ephrin family. The natural hosts are predominantly bats, mainly the Pteropus genus of megabats (flying foxes) and some microbats. Bats infected with Hendra virus develop viraemia and shed virus in urine, faeces and saliva for around a week, but show no signs of disease. Henipaviruses can also infect humans and livestock, causing severe disease with high mortality, making the group a zoonootic disease. Transmission to humans sometimes occurs via an intermediate domestic animal host.

The first henipavirus, Hendra virus, was discovered in 1994 as the cause of an outbreak in horses in Brisbane, Australia. Nipah virus was identified a few years later in Malaysia as the cause of an outbreak in pigs. Three further species have since been recognised: Cedar and Kumasi viruses in bats, and Mòjiāng virus in rodents. Their emergence as human pathogens has been linked to increased contact between bats and humans. Human disease has been confined to Australia and Asia, but members of the genus have also been found in African bats. A veterinary vaccine against Hendra virus is available but no human vaccine has been licensed.

Did you know?

- ...that sarcoids (pictured) are non-fatal tumours but are a common reason for euthanasia in horses?

- ...that the arrest of Brownie Mary led to one of the first clinical trials studying the effects of cannabinoids in HIV-infected adults?

- ...that eradication of infectious diseases can come about through vaccination, quarantine, and even just human behavioural changes, depending on the disease?

- ...that Albert Sabin, developer of the oral polio vaccine, called Robert M. Chanock his "star scientific son"?

- ...that Millennium's second season finale "The Time Is Now" was inspired in part by a cattle disease in the United Kingdom?

Selected biography

Edward Jenner (1749–1823) was an English physician and scientist who pioneered the smallpox vaccine, the world's first vaccine. Noting the common observation that milkmaids were generally immune to smallpox, Jenner postulated that the pus in the blisters that milkmaids received from cowpox (a similar but much less virulent disease) protected them from smallpox. In 1796, Jenner tested his hypothesis by inoculating an eight-year-old boy with pus from an infected milkmaid. He subsequently repeatedly challenged the boy with variolous material, then the standard method of immunisation, without inducing disease. He published a paper including 23 cases in 1798. Although several others had previously inoculated subjects with cowpox, Jenner was the first to show that the procedure induced immunity to smallpox. He later successfully popularised cowpox vaccination.

Jenner is often called "the father of immunology", and his work is said to have saved more lives than that of any other individual.

In this month

1 July 1796: Edward Jenner first challenged James Phipps with variolation, showing that cowpox inoculation is protective against smallpox

3 July 1980: Structure of southern bean mosaic virus solved by Michael Rossmann and colleagues

6 July 1885: Louis Pasteur (pictured) gave rabies vaccine to Joseph Meister

10 July 1797: Jenner submitted paper on Phipps and other cases to the Royal Society; it was read to the society but not published

14–20 July 1968: First International Congress for Virology held in Helsinki

16 July 2012: FDA approved tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada) for prophylactic use against HIV; first prophylactic antiretroviral

19 July 2013: Pandoravirus described, with a genome twice as large as Megavirus

22 July 1966: International Committee on Nomenclature of Viruses (later the ICTV) founded

25 July 1985: Film star Rock Hudson made his AIDS diagnosis public, increasing public awareness of the disease

28 July 2010: First global World Hepatitis Day

Selected intervention

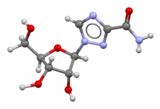

Ribavirin is a nucleoside analogue that mimics the nucleoside guanosine. It shows some activity against a broad range of DNA and RNA viruses, but is less effective against dengue fever, yellow fever and other flaviviruses. The drug was first synthesised in the early 1970s by Joseph T. Witkowski and Roland K. Robins. Ribavirin's main current use is against hepatitis C, in combination with pegylated interferon, nucleotide analogues and protease inhibitors. It has been used in the past in an aerosol formulation against respiratory syncytial virus-related diseases in children. Ribavirin has been used in combination as part of an experimental treatment for rabies. It is also the only available treatment for the viruses causing some viral haemorrhagic fevers, including Lassa fever, Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever and hantavirus disease, but is ineffective against the filovirus diseases, Ebola and Marburg. Clinical use is limited by the drug building up in red blood cells to cause haemolytic anaemia.

Subcategories

Subcategories of virology:

Topics

Things to do

- Comment on what you like and dislike about this portal

- Join the Viruses WikiProject

- Tag articles on viruses and virology with the project banner by adding {{WikiProject Viruses}} to the talk page

- Assess unassessed articles against the project standards

- Create requested pages: red-linked viruses | red-linked virus genera

- Expand a virus stub into a full article, adding images, citations, references and taxoboxes, following the project guidelines

- Create a new article (or expand an old one 5-fold) and nominate it for the main page Did You Know? section

- Improve a B-class article and nominate it for Good Article

or Featured Article

or Featured Article status

status - Suggest articles, pictures, interesting facts, events and news to be featured here on the portal

WikiProjects & Portals

WikiProject Viruses

Related WikiProjects

WikiProject Viruses

Related WikiProjects

Medicine • Microbiology • Molecular & Cellular Biology • Veterinary Medicine

Related PortalsAssociated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikispecies

Directory of species -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search