Back Protestantse Hervorming Afrikaans Reformation ALS Reforma protestant AN Cirice Edniwung ANG धर्मसुधार आन्दोलन ANP إصلاح بروتستانتي Arabic تعديل بروتيستانتى ARZ খ্ৰীষ্টান ধৰ্মসংস্কাৰ আন্দোলন Assamese Reforma protestante AST Реформация AV

| Part of a series on the |

| Reformation |

|---|

|

| Protestantism |

| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation,[1] was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and the authority of the Catholic Church. Towards the end of the Renaissance, the Reformation marked the beginning of Protestantism. It is considered one of the events that signified the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the early modern period in Europe.[2]

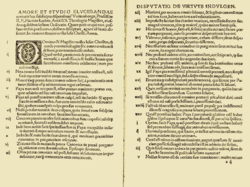

The Reformation is usually dated from Martin Luther's publication of the Ninety-five Theses in 1517, which gave birth to Lutheranism. Prior to Martin Luther and other Protestant Reformers, there were earlier reform movements within Western Christianity. The end of the Reformation era is disputed among modern scholars.

In general, the Reformers argued that justification was based on faith in Jesus alone and not both faith and good works, as in the Catholic view. In the Lutheran, Anglican and Reformed view, good works were seen as fruits of living faith and part of the process of sanctification.[3][4] Protestantism also introduced new ecclesiology. The general points of theological agreement by the different Protestant groups have been more recently summarized as the three solae, though various Protestant denominations disagree on doctrines such as the nature of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, with Lutherans accepting a corporeal presence and the Reformed accepting a spiritual presence.[5][6]

The spread of Gutenberg's printing press provided the means for the rapid dissemination of religious materials in the vernacular. The initial movement in Saxony, Germany, diversified, and nearby other reformers such as the Swiss Huldrych Zwingli and the French John Calvin developed the Continental Reformed tradition. Within a Reformed framework, Thomas Cranmer and John Knox led the Reformation in England and the Reformation in Scotland, respectively, giving rise to Anglicanism and Presbyterianism.[7][8][9] The period also saw the rise of non-Catholic denominations with quite different theologies and politics to the Magisterial Reformers (Lutherans, Reformed, and Anglicans): so-called Radical Reformers such as the various Anabaptists, who sought to return to the practices of early Christianity.[10][11][12] The Counter-Reformation comprised the Catholic response to the Reformation, with the Council of Trent clarifying ambiguous or disputed Catholic positions and abuses that had been subject to critique by reformers.[13]

The consequent European wars of religion saw the deaths of between seven and seventeen million people.

- ^ Armstrong, Alstair (2002). European Reformation: 1500–1610 (Heinemann Advanced History): 1500–55. Heinemann Educational. ISBN 0-435-32710-0.

- ^ Davies 1996, p. 291.

- ^ Bray, Gerald (3 March 2021). Anglicanism. Lexham Press. ISBN 978-1-68359-437-6.

The doctrine of justification by faith alone was the central teaching of the Lutheran Reformation and is fully accepted by Anglicans.

- ^ Harstad, Adolph L. (10 May 2016). "Justification Through Faith Produces Sanctification". Evangelical Lutheran Synod.

- ^ Bente, Friedrich (2 December 2021). Historical Introductions to the Symbolical Books of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. Litres. ISBN 978-5-04-061695-4.

In fact Calvin must be regarded as the real originator of the second controversy on the Lord's Supper between the Lutherans and the Reformed

- ^ Nevin, John Williamson (19 April 2012). The Mystical Presence: And The Doctrine of the Reformed Church on the Lord's Supper. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. xxviii. ISBN 978-1-61097-169-0.

In The Mystical Presence Neven maintained that John Calvin, the foremost architect of Reformed doctrine, included the real spiritual presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

- ^ Null, Ashley; Yates III, John W. (14 February 2017). Reformation Anglicanism (The Reformation Anglicanism Essential Library, Volume 1): A Vision for Today's Global Communion. Crossway. ISBN 978-1-4335-5216-8.

Therefore, Cranmer fully integrated justificton sola fide et sola gratia into the doctrine and worship of the Church of Englan. His "Homily on Salvation" taught these principles to every parish in the country on a regular basis. Several of the Articles of Religion make the Protestant understanding of justification normative for Anglican doctrine (Articles 9-14, 17, 22).

- ^ González, Justo L. (1987). A History of Christian Thought: From the Protestant Reformation to the twentieth century. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0-687-17184-2.

It is clear that, in rejecting Roman Catholic doctrine on this point, Cranmer has also rejected Luther's views and adopted Calvin's position. The sacrament is not merely a symbol of what takes place in the heart, but neither is it the physical eating of the body of Christ. This must be so, because the body of Christ is in heaven and therefore our participation in it can only be spiritual. Only the believers are the true partakers of the body and blood of Christ, for the unbelievers eat and drink no more than bread and wine—and condemnation upon themseves, for the profanation of the Lord's Table. These views are reflected in the Thirty-nine articles, of which the twenty-eighth says that "the Body of the Christ is given, taken, and eaten, in the Supper, only after an heavently and spiritual manner. The next article says of the wicked that "in no wise are they partakers of Christ," although "to their condemnation [they] do eat and rink the sign or Sacrament of so great a thing." This marked Calvinistic influence would prove very significant for the history of Christianity in England during the seventeenth century

- ^ Fortson III, S. Donald (4 December 2017). The Presbyterian Story: Origins & Progress of a Reformed Tradition, 2nd Edition. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-7252-3817-6.

in Scotland the story was a striking contrast as a national Sottish Presbyterian Church was the outcome. The Reformation in Sotland, in manifold ways, was the by-product of Herculean efforts by John Knox, "the Father of Presbyterianism."

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Shah2016was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Cremeens2018was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Pettegree 2000b, p. 242.

- ^ "Counter Reformation". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 9 October 2023.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search