Back هيوسين Arabic Escopolamina AST هیوسین AZB Hostis BCL স্কোপোলামিন Bengali/Bangla Skopolamin BS Escopolamina Catalan Skopolamin Czech Hyoscin Welsh Scopolamin Danish

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Transderm Scop, others |

| Other names | Hyoscine[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682509 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, transdermal, ophthalmic, subcutaneous, intravenous, sublingual, rectal, buccal, transmucosal, intramuscular |

| Drug class | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 20-40%[7] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A4)[8] |

| Elimination half-life | 5 hours[7] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.083 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

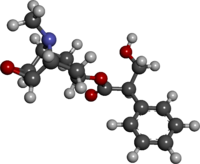

| Formula | C17H21NO4 |

| Molar mass | 303.358 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Scopolamine, also known as hyoscine,[9] or Devil's Breath,[10] is a natural or synthetically produced tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic drug that is used as a medication to treat motion sickness[11] and postoperative nausea and vomiting.[12][1] It is also sometimes used before surgery to decrease saliva.[1] When used by injection, effects begin after about 20 minutes and last for up to 8 hours.[1] It may also be used orally and as a transdermal patch since it has been long known to have transdermal bioavailability.[1][13]

Scopolamine is in the antimuscarinic family of drugs and works by blocking some of the effects of acetylcholine within the nervous system.[1]

Scopolamine was first written about in 1881 and started to be used for anesthesia around 1900.[14][15] Scopolamine is also the main active component produced by certain plants of the nightshade family, which historically have been used as psychoactive drugs, known as deliriants, due to their antimuscarinic-induced hallucinogenic effects in higher doses.[12] In these contexts, its mind-altering effects have been utilized for recreational and occult purposes.[16][17][18] The name "scopolamine" is derived from one type of nightshade known as Scopolia, while the name "hyoscine" is derived from another type known as Hyoscyamus niger, or black henbane.[19][20] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[21]

- ^ a b c d e f "Scopolamine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Scopolamine Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 6 September 2023. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Poisons Standard October 2020". Federal Register of Legislation. 30 September 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Hyoscine 400 micrograms/ml Solution for Injection". (emc). 18 September 2017. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Kwells 300 microgram tablets Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 2 September 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Transderm Scop - scopolamine patch, extended release". DailyMed. 14 March 2024. Archived from the original on 30 November 2023. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ a b Putcha L, Cintrón NM, Tsui J, Vanderploeg JM, Kramer WG (June 1989). "Pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability of scopolamine in normal subjects". Pharmaceutical Research. 06 (6): 481–485. doi:10.1023/A:1015916423156. PMID 2762223. S2CID 27507555.

- ^ Renner UD, Oertel R, Kirch W (October 2005). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in clinical use of scopolamine". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 27 (5): 655–665. doi:10.1097/01.ftd.0000168293.48226.57. PMID 16175141. S2CID 32720769.

- ^ Juo PS (2001). Concise Dictionary of Biomedicine and Molecular Biology (2nd ed.). Hoboken: CRC Press. p. 570. ISBN 978-1-4200-4130-9. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ Duffy R (23 July 2007). "Colombian Devil's Breath". Vice. Archived from the original on 18 April 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ "About hyoscine hydrobromide". nhs.uk. 24 October 2022. Archived from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ a b Osbourn AE, Lanzotti V (2009). Plant-derived Natural Products: Synthesis, Function, and Application. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-387-85498-4. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ Sollmann T (1957). A Manual of Pharmacology and Its Applications to Therapeutics and Toxicology (8th ed.). Philadelphia and London: W.B. Saunders.

- ^ Keys TE (1996). The history of surgical anesthesia (PDF) (Reprint ed.). Park Ridge, Ill.: Wood Library, Museum of Anesthesiology. p. 48ff. ISBN 978-0-9614932-7-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 551. ISBN 978-3-527-60749-5.

- ^ Kennedy DO (2014). "The Deliriants - The Nightshade (Solanaceae) Family". Plants and the Human Brain. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 131–137. ISBN 978-0-19-991401-2. LCCN 2013031617. Archived from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Uribe_et_al_2005was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Raetsch C (2005). The encyclopedia of psychoactive plants: ethnopharmacology and its applications. US: Park Street Press. pp. 277–282.

- ^ The Chambers Dictionary. Allied Publishers. 1998. pp. 788, 1480. ISBN 978-81-86062-25-8.

- ^ Cattell HW (1910). Lippincott's new medical dictionary: a vocabulary of the terms used in medicine, and the allied sciences, with their pronunciation, etymology, and signification, including much collateral information of a descriptive and encyclopedic character. Lippincott. p. 435. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search