Back Tien Verlore Stamme Afrikaans الأسباط العشرة المفقودة Arabic غیب اولموش اون قبیله AZB Десет изгубени колена Bulgarian দশ নিখোঁজ বংশ Bengali/Bangla Verlorene Stämme Israels German Dek Perditaj Triboj Esperanto Diez tribus perdidas Spanish ده قبیله گمشده Persian Israelin kadonneet heimot Finnish

| Tribes of Israel |

|---|

|

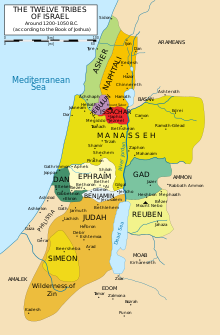

The Ten Lost Tribes were the ten of the Twelve Tribes of Israel that were said to have been exiled from the Kingdom of Israel after its conquest by the Neo-Assyrian Empire c. 722 BCE.[1][2] These are the tribes of Reuben, Simeon, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, Manasseh, and Ephraim — all but Judah, Benjamin, and some members of the priestly Tribe of Levi, which did not have its own territory.

The Jewish historian Josephus (37–100 CE) wrote that "there are but two tribes in Asia and Europe subject to the Romans, while the ten tribes are beyond Euphrates till now, and are an immense multitude, and not to be estimated by numbers".[3] In the 7th and 8th centuries CE, the return of the lost tribes was associated with the concept of the coming of the messiah.[4]: 58–62 Claims of descent from the "lost tribes" have been proposed in relation to many groups,[5] and some religions espouse a messianic view that the tribes will return.

According to contemporary research, Transjordan and Galilee did witness large-scale deportations, and entire tribes were lost. Historians have generally concluded that the deported tribes assimilated into the local population. In Samaria, on the other hand, many Israelites survived the Assyrian onslaught and remained in the land, eventually forming the Samaritan community.[6][7] However, this has not stopped various religions from asserting that some survived as distinct entities. Zvi Ben-Dor Benite, a professor of Middle Eastern history, states: "The fascination with the tribes has generated, alongside ostensibly nonfictional scholarly studies, a massive body of fictional literature and folktale."[4]: 11 Anthropologist Shalva Weil has documented various differing tribes and peoples claiming affiliation to the Lost Tribes throughout the world.[8]

- ^ Josephus, The Antiquities of the Jews, Book 11 chapter 1

- ^ 2 Esdras 13:39–45

- ^ Josephus, Flavius. Antiquites. p. 11:133.

- ^ a b Benite, Zvi Ben-Dor (2009). The Ten Lost Tribes: A World History. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780195307337.

- ^ Weil, Shalva (2015). "Tribes, Ten Lost". In Patai, Raphael; Bar -Itzhak, Haya (eds.). Encyclopedia of Jewish Folklore and Traditions. Vol. 2. Routledge. pp. 542–543. ISBN 9781317471714.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Knoppers, Gary (2013). "The Fall of the Northern Kingdom and the Ten Lost Tribes: A Reevaluation". Jews and Samaritans: The Origins and History of Their Early Relations. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 42–44. ISBN 978-0-19-006879-0.

What one finds in the Samarian hills is not the wholesale replacement of one local population by a foreign population, but rather the diminution of the local population. Widespread abandonment does not occur as in parts of Galilee and Gilead, but significant depopulation does occur. Among the causes of such a decline one may list death by war, disease, and starvation; forced deportations to other lands; and migrations to other areas, including south to Judah. [...] This brings us back to the question with which we began: What happened to the "ten lost tribes?" A significant portion of the "ten lost tribes" was never lost. In the region of Samaria, most of the indigenous Israelite population—those who survived the Assyrian onslaughts—remained in the land.

- ^ Weil, S. 1991 Beyond the Sambatyon: the Myth of the Ten Lost Tribes. Tel-Aviv: Beth Hatefutsoth, the Nahum Goldman Museum of the Jewish Diaspora.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search