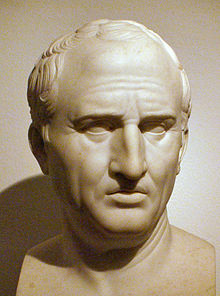

Marcus Tullius Cicero | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 3, 106 BC Arpinum, Italy |

| Died | December 7, 43 BC Formia, Italy |

| Occupation | Politician, lawyer, orator and philosopher |

| Nationality | Ancient Roman |

| Subject | politics, law, philosophy, oratory |

| Literary movement | Golden Age Latin |

| Notable works | Orations: In Verrem, In Catilinam I–IV, Philippicae Philosophy: De Oratore, De Re Publica, De Legibus, De Finibus, De Natura Deorum, De Officiis |

The writings of Marcus Tullius Cicero constitute one of the most renowned collections of historical and philosophical work in all of classical antiquity. Cicero was a Roman politician, lawyer, orator, political theorist, philosopher, and constitutionalist who lived during the years of 106–43 BC. He held the positions of Roman senator and Roman consul (chief-magistrate) and played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He was extant during the rule of prominent Roman politicians, such as those of Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Marc Antony. Cicero is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.[1][2]

Cicero is generally held to be one of the most versatile minds of ancient Rome. He introduced the Romans to the chief schools of Greek philosophy, and also created a Latin philosophical vocabulary; distinguishing himself as a linguist, translator, and philosopher. A distinguished orator and successful lawyer, Cicero likely valued his political career as his most important achievement. Today he is appreciated primarily for his humanism and philosophical and political writings. His voluminous correspondence, much of it addressed to his friend Atticus, has been especially influential, introducing the art of refined letter writing to European culture. Cornelius Nepos, the 1st-century BC biographer of Atticus, remarked that Cicero's letters to Atticus contained such a wealth of detail "concerning the inclinations of leading men, the faults of the generals, and the revolutions in the government" that their reader had little need for a history of the period.[3]

During the chaotic latter half of the first century BC, marked by civil wars and the dictatorship of Gaius Julius Caesar, Cicero championed a return to the traditional republican government. However, his career as a statesman was marked by inconsistencies and a tendency to shift his position in response to changes in the political climate. His indecision may be attributed to his sensitive and impressionable personality; he was prone to overreaction in the face of political and private change. "Would that he had been able to endure prosperity with greater self-control and adversity with more fortitude!" wrote C. Asinius Pollio, a contemporary Roman statesman and historian.[4][5]

A manuscript containing Cicero's letters to Atticus, Quintus, and Brutus was rediscovered by Petrarch in 1345 at the Capitolare library in Verona. This rediscovery is often credited for initiating the 14th-century Italian Renaissance, and for the founding of Renaissance humanism.[6]

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero, a portrait (1975) p. 303

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero (1964) pp. 300–01

- ^ Cornelius Nepos, Atticus 16, trans. John Selby Watson.

- ^ Haskell, H.J.:"This was Cicero" (1964) p. 296

- ^ Castren and Pietilä-Castren: "Antiikin käsikirja" /"Handbook of antiquity" (2000) p. 237

- ^ "History". Biblioteca Capitolare di Verona. Retrieved 2022-11-16.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search