Back الفجر الذهبي (اليونان) Arabic Qızıl Şəfəq (Yunanıstan) Azerbaijani Златна зора Bulgarian Alba Daurada Catalan Zlatý úsvit (politická strana) Czech Gwawr Euraid Welsh Gyldent Daggry Danish Chrysi Avgi German Χρυσή Αυγή Greek Golden Dawn (Greece) English

| Amanecer Dorado Χρυσή Αυγή | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Secretario/a general | Nikolaos Michaloliakos | |

| Fundación | 1 de enero de 1985 | |

| Ilegalización | 7 de octubre de 2020 | |

| Eslogan | Patria, Honor, Amanecer Dorado (Πατρίδα, Τιμή, Χρυσή Αυγή) | |

| Ideología |

Ultranacionalismo[1][2] Neofascismo Neonazismo[3][4][5][6][7] Euroescepticismo[8][9][10][11] Metaxismo[12][13] Gran Idea Panhelenismo Antiglobalización Antiinmigración Populismo de derecha[14] | |

| Posición | Extrema derecha[15] | |

| Sede |

Atenas, | |

| País |

| |

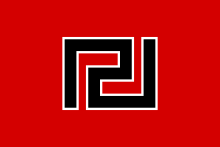

| Colores | Negro y Rojo | |

| Himno | Himno del Amanecer Dorado (Ύμνος Χρυσής Αυγής) | |

| Organización juvenil | Frente de la Juventud | |

| Consejo de los Helenos |

0/300 | |

| Europarlamento |

0/21 | |

| Consejos Regionales |

22/703 | |

| Publicación | Chrysi Avgi | |

| Sitio web | www.xrisiavgi.com/ | |

Amanecer Dorado (en griego: Χρυσή Αυγή, Chrysí Avgí, AFI: [xriˈsi avˈʝi]; a veces traducido como Alba Dorada o Aurora Dorada), cuyo nombre oficial es Asociación Popular - Amanecer Dorado[16][17] (en griego: Λαϊκός Σύνδεσμος - Χρυσή Αυγή, Laïkós Sýndesmos - Chrysí Avgí) es un partido político griego ilegalizado, de ideología neonazi[18][19][20][21][22] y fascista.[21][23][24] Estaba encabezado por Nikolaos Michaloliakos, un exmilitar que formó parte del cuerpo de paracaidistas del ejército griego y que en 1978 fue detenido por posesión ilegal de armas y explosivos. El 7 de octubre de 2020 fue declarado una organización criminal, según la sentencia de la jueza Maria Lepenioti.[22][25] Esto ocurrió a raíz del asesinato del rapero Pavlos Fyssas en 2013. El Tribunal de Apelaciones de Atenas dictaminó que Amanecer Dorado operaba como una organización criminal atacando sistemáticamente a inmigrantes e izquierdistas. El tribunal también anunció veredictos para 68 acusados, incluido el liderazgo político del partido. Nikolaos Michaloliakos y otros seis miembros destacados y ex diputados, acusados de dirigir una organización criminal, fueron declarados culpables.[26] También se dictaron veredictos de asesinato, intento de asesinato y ataques violentos contra inmigrantes y opositores políticos de izquierda.[27]

Amanecer Dorado accedió por primera vez en el Consejo de los Helenos (parlamento griego) en mayo de 2012, obteniendo 21 diputados y el 7 % de los votos.[28] Tras las elecciones del mes siguiente, obtuvo prácticamente el mismo resultado, el 6,9 % de los votos, pero perdiendo tres escaños, quedando representado finalmente con 18 diputados.[29]

En las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo de 2014 obtuvo un 9.4 % de los votos, convirtiéndose en el tercer partido de Grecia.[30] En las elecciones parlamentarias de enero de 2015, quedó de nuevo como tercera fuerza con un 6,3% de los votos, perdiendo solo un escaño respecto a las anteriores elecciones parlamentarias, a pesar de tener a toda su cúpula en la cárcel.[31] En las elecciones parlamentarias de septiembre de 2015, obtuvo por tercera vez el tercer puesto con un 7% de los votos, ganando un escaño adicional.

En las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo de 2019 obtuvo un 4.9 % de los votos, disminuyendo su representación a dos eurodiputados.

En las elecciones parlamentarias de 2019 perdió su representación en el Consejo de los Helenos con un 2,93% de los votos. Esto se atribuyó a la pérdida de popularidad del partido durante el juicio por el asesinato de Fyssas.[32] A finales de 2019 se informó que el partido cerró sus sedes en Atenas y Pireo ante la imposibilidad de pagar el alquiler y cerró también su página web.[33][34]

- ↑ Tsatsanis, Emmanouil (2011), «Hellenism under siege: the national-populist logic of antiglobalization rhetoric in Greece», Journal of Political Ideologies (en inglés) 16 (1): 11-31, doi:10.1080/13569317.2011.540939, «...and far right-wing newspapers such as Alpha Ena, Eleytheros Kosmos, Eleytheri Ora and Stohos (the mouthpiece of ultra-nationalist group Chrysi Avgi).».

- ↑ Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth (2006), Reputational Shields: Why Most Anti-Immigrant Parties Failed in Western Europe, 1980–2005 (en inglés), Nuffield College, Universidad de Oxford, p. 15.

- ↑

- Wodak, Ruth (2015), The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean, Sage, «However, Golden Dawn's neo-Nazi profile is clearly visible in the party's symbolism, with its flag resembling a swastika, Nazi salutes and chant of 'Blood and Honour' encapsulating its xenophobic and racist ideology.».

- Vasilopoulou; Halikiopoulou (2015), The Golden Dawn's 'Nationalist Solution', p. 32, «The extremist character of the Golden Dawn, its neo-Nazi principles, racism and ultranationalism, as well as its violence, render the party a least likely case of success...».

- Dalakoglou, Dimitris (2013), «Neo-Nazism and neoliberalism: A Few Comments on Violence in Athens At the Time of Crisis», WorkingUSA: The Journal of Labor and Society (16(2).

- Miliopoulos, Lazaros (2011), «Extremismus in Griechenland», Extremismus in den EU-Staaten (en alemán) (VS Verlag): 154, doi:10.1007/978-3-531-92746-6_9, «...mit der seit 1993 als Partei anerkannten offen neonationalsozialistischen Gruppierung Goldene Mörgenröte (Chryssi Avgí, Χρυσή Αυγή) kooperierte... [...cooperated with the openly neo-National Socialist group Golden Dawn (Chryssi Avgí, Χρυσή Αυγή), which has been recognized as a party since 1993...]».

- Davies, Peter; Jackson, Paul (2008), The Far Right in Europe: An Encyclopedia, Greenwood World Press, p. 173.

- Altsech, Moses (agosto de 2004), «Anti-Semitism in Greece: Embedded in Society», Post-Holocaust and Anti-Semitism (23): 12, «On 12 March 2004, Chrysi Avghi (Golden Dawn), the new weekly newspaper of the Neo-Nazi organization of that name, cited another survey indicating that the percentage of Greeks who view immigrants unfavorably is 89 percent.».

- ↑ Explosion at Greek neo-Nazi office, CNN, 19 de marzo de 2010, archivado desde el original el 8 de marzo de 2012, consultado el 2 de febrero de 2012.

- «Beyond Spontaneity», CITY 16 (5), 2012, doi:10.1080/13604813.2012.720760.

- ↑ Donadio, Rachel; Kitsantonis, Niki (6 de mayo de 2012), «Greek Voters Punish 2 Main Parties for Economic Collapse», New York Times.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ «‘Protocols of the Elders of Zion’ read aloud in Greek parliament» (en inglés). The Times of Israel. 26 de octubre de 2012. Consultado el 29 de septiembre de 2013. «Ilias Kasidiaris, a spokesperson for Golden Dawn, read out Protocol 19 from the book: “In order to destroy the prestige of heroism we shall send them for trial in the category of theft, murder and every kind of abominable and filthy crime”».

- ↑ «In crisis-ridden Europe, euroscepticism is the new cultural trend». 10 de octubre de 2012. Archivado desde el original el 4 de diciembre de 2013. Consultado el 17 de octubre de 2015.

- ↑ Smith, Helena (16 de diciembre de 2011), «Rise of the Greek far right raises fears of further turmoil», The Guardian (London).

- ↑ Dalakoglou, Dimitris (2012), «Beyond Spontaneity: Crisis, Violence and Collective Action in Athens», CITY 16 (5): 535-545, doi:10.1080/13604813.2012.720760, «The use of the terms extreme-Right, neo-Nazi, and fascist as synonymous is on purpose. Historically in Greece, the terms have been used alternatively in reference to the para-state apparatuses, but not only. (pg: 542)».

- ↑

- Xenakis, Sappho (2012), «A New Dawn? Change and Continuity in Political Violence in Greece», Terrorism and Political Violence 24 (3): 437-64, doi:10.1080/09546553.2011.633133, «...Nikolaos Michaloliakos, who in the early 1980s established the fascistic far-right party Chrysi Avgi ("Golden Dawn").».

- Kravva, Vasiliki (2003), «The Construction of Otherness in Modern Greece», The Ethics of Anthropology: Debates and dilemmas (Routledge): 169, «For example, during the summer of 2000 members of Chryssi Avgi, the most widespread fascist organization in Greece, destroyed part of the third cemetery in Athens...».

- ↑ van Versendaal, Harry (13 de febrero de 2013). «Mazower warns Greece is underestimating threat of Golden Dawn». Kathimerini (en inglés). Kathimerini.

- ↑ «Το κλούβιο «αβγό του φιδιού»» (en griego). To Bhma. 9 de noviembre de 2005.

- ↑ Independent: The Golden Dawn: A love of power and a hatred of difference on the rise in the cradle of democracy, "The economic ethos of European neo-fascism, from the Golden Dawn to the British National Party, has historically been anti-neoliberal and anti-globalization", 14-10-2012

- ↑ Vasilopoulou y Halikiopoulou, 2015, pp. 1-3.

- ↑ Galiatsatos, Panagis (1 de octubre de 2013), «Golden Dawn: From fringe group to game changer», Kathimeriní.

- ↑ Ellinas (2013), The Rise of the Golden Dawn, p. 21.

- ↑

- Miliopoulos, Lazaros (2011), «Extremismus in Griechenland», Extremismus in den EU-Staaten (en alemán) (VS Verlag): 154, doi:10.1007/978-3-531-92746-6_9, «...mit der seit 1993 als Partei anerkannten offen neonationalsozialistischen Gruppierung Goldene Mörgenröte (Chryssi Avgí, Χρυσή Αυγή) kooperierte... [...cooperated with the openly neo-National Socialist group Golden Dawn (Chryssi Avgí, Χρυσή Αυγή), which has been recognized as a party since 1993...]».

- Davies, Peter; Jackson, Paul (2008), The Far Right in Europe: An Encyclopedia, Greenwood World Press, p. 173.

- Chalk, Peter (2003), «Non-Military Security in the Wider Middle East», Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 26 (3): 197-214, doi:10.1080/10576100390211428, «Reflecting these perceptions has been a growing sub-culture of support for neo-Nazi hate groups such as Troiseme Voie in France, Golden Dawn in Greece, Combat 18 (C18) in the United Kingdom...».

- Altsech, Moses (agosto de 2004), «Anti-Semitism in Greece: Embedded in Society», Post-Holocaust and Anti-Semitism (23): 12, «On 12 March 2004, Chrysi Avghi (Golden Dawn), the new weekly newspaper of the Neo-Nazi organization of that name, cited another survey indicating that the percentage of Greeks who view immigrants unfavorably is 89 percent.».

- Porat, Dina; Stauber, Roni (2002), Antisemitism Worldwide 2000/1, University of Nebraska Press, p. 123, «The neo-Nazi Chrissi Avgi (Golden Daybreak) was the only far right group active in 2000. It was responsible for at least one antisemitic act and for attacks against left-wing targets.».

- ↑ * «Explosion at Greek neo-Nazi office», CNN, 19 de marzo de 2010, archivado desde el original el 8 de marzo de 2012, consultado el 2 de febrero de 2012.

- «Greek minister warns of neo-Nazi political threat», B92, 31 de marzo de 2012, archivado desde el original el 3 de junio de 2012.

- «Ακροδεξιά απειλή για τη Δημοκρατία (Right-wing threat to Democracy)», Ethnos, 31 de marzo de 2012.

- «Migration woes take centre stage ahead of Greek election», The Sun Daily, 4 de abril de 2012, archivado desde el original el 8 de enero de 2014.

- ↑ Donadio, Rachel; Kitsantonis, Niki (6 de mayo de 2012), «Greek Voters Punish 2 Main Parties for Economic Collapse», New York Times.

- ↑ a b Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; no se ha definido el contenido de las referencias llamadasRT2 - ↑ a b Página12 (1602073620). «Grecia: declaran "organización criminal" al partido neonazi Amanecer Dorado | Sus integrantes enfrentan penas de entre 5 y 15 años de prisión». PAGINA12. Consultado el 7 de octubre de 2020.

- ↑

- Xenakis, Sappho (2012), «A New Dawn? Change and Continuity in Political Violence in Greece», Terrorism and Political Violence 24 (3): 437-64, doi:10.1080/09546553.2011.633133, «...Nikolaos Michaloliakos, who in the early 1980s established the fascistic far-right party Chrysi Avgi (“Golden Dawn”).».

- Kravva, Vasiliki (2003), «The Construction of Otherness in Modern Greece», The Ethics of Anthropology: Debates and dilemmas (Routledge): 169, «For example, during the summer of 2000 members of Chryssi Avgi, the most widespread fascist organization in Greece, destroyed part of the third cemetery in Athens...».

- ↑ Smith, Helena (16 de diciembre de 2011), «Rise of the Greek far right raises fears of further turmoil», The Guardian.

- ↑ de 2020, 7 de Octubre. «La Justicia griega declaró al líder del partido neonazi Amanecer Dorado culpable de “dirigir una organización criminal”: disturbios en Atenas». infobae. Consultado el 7 de octubre de 2020.

- ↑ Kokkinidis, Tasos (7 de octubre de 2020). «Neo-Nazi Golden Dawn is a Criminal Organization, Greek Court Rules». GreekReporter.com.

- ↑ «Greece Golden Dawn: Neo-Nazi leaders guilty of running crime gang». BBC News. 7 de octubre de 2020.

- ↑ Cooper, Rob (7 de mayo de 2012). «Rise of the Greek neo-Nazis: Ultra-right party Golden Dawn wants to force immigrants into work camps and plant landmines along Turkish border». Daily Mail.

- ↑ «Los griegos votan por el rescate». El País. 18 de junio de 2012.

- ↑ «Αποτελέσματα Επικράτειας». 2014. Archivado desde el original el 25 de octubre de 2015. Consultado el 5 de junio de 2014.

- ↑ Sánchez-Vallejo, María Antonia (26 de enero de 2015). «Tsipras toma posesión tras pactar con ANEL el apoyo para su gobierno». El País. Consultado el 26 de enero de 2015.

- ↑ «Amanecer Dorado: los neonazis de Grecia, fuera del parlamento y cada vez más cerca de la cárcel». ABC. 8 de julio de 2019. Consultado el 17 de julio de 2019.

- ↑ «Amanecer Dorado se desmorona en Grecia seis años después del asesinato que frenó su auge». Publico. 2019. Consultado el 5 de noviembre de 2019.

- ↑ F. Ferrero, Javier (2019). «El final de Amanecer Dorado: el partido neonazi griego ya no puede ni pagar el alquiler». Contrainformacion.es. Consultado el 5 de noviembre de 2019.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search