Back Slang Afrikaans Schlangen ALS እባብ Amharic Serpentes AN Snaca ANG सर्प ANP ثعبان Arabic ܚܘܝܐ ARC تعبان ARZ সাপ Assamese

| Snakes | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Clade: | Ophidia |

| Suborder: | Serpentes Linnaeus 1758 |

| Infraorders | |

| |

| |

| Approximate world distribution of snakes, all species | |

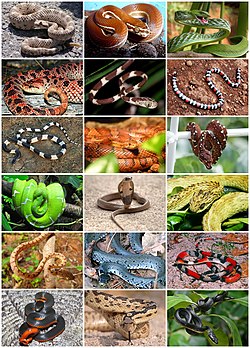

Snakes are reptiles. They are part of the order Squamata. They are carnivores, with long narrow bodies and no legs. There are at least 20 families, about 500 genera and 3,400 species of snake.[2][3]

The earliest known fossils are from the Jurassic period. This was between 143 and 167 million years ago.[4]

Their long, slender body has some special features.[5] They have overlapping scales which protect them, and help them move and climb trees. The scales have colours which may be camouflage or warning colours.

Many species have skulls with more joints than the skulls of their lizard ancestors. This allows the snakes to swallow prey much larger than their heads. In their narrow bodies, snakes' paired organs (such as kidneys) appear one in front of the other instead of side by side. Most have only one working lung. Some species have kept a pelvic girdle with a pair of vestigial claws on either side of the cloaca. They have no eyelids or external ears. They can hiss, but otherwise make no vocal sounds.

They are very mobile in their own way. Most of them live in the tropics. Few snake species live beyond the Tropic of Cancer or Tropic of Capricorn, and only one species, the common viper (Vipera berus) lives beyond the Arctic Circle.[5] They can see well enough, and they can taste scents with their tongues by flicking them in and out. They are very sensitive to vibrations in the ground. Some snakes can sense warm-blooded animals by thermal infrared.

Most snakes live on the ground, and in the trees. Others live in the water, and a few live under the soil. Like other reptiles, snakes are ectotherms. They control their body temperature by moving in and out of the direct sunshine. That is why they are rare in cold places.[6]

Snakes range in size from the tiny, 10.4 cm (4 inch)-long thread snake[7] to the reticulated python of 6.95 meters (22.8 ft) in length.[8] The extinct snake Titanoboa was 12.8 meters (42 ft) long.[9]

- ↑ Hsiang, A.Y.; et al. (2015). "The origin of snakes: Revealing the ecology, behavior, and evolutionary history of early snakes using genomics, phenomics, and the fossil record". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 15: 87. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0358-5. PMC 4438441. PMID 25989795.

- ↑ "Serpentes". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ↑ snake species list at the Reptile Database. Accessed 22 May 2012.

- ↑

Perkins, Sid (27 January 2015). "Fossils of oldest known snakes unearthed". news.sciencemag.org. Archived from the original on 30 January 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

Caldwell, M. W.; Nydam, R. L.; Palci, A.; Apesteguía, S. (2015). "The oldest known snakes from the Middle Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous provide insights on snake evolution". Nature Communications. 6 (5996): 5996. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.5996C. doi:10.1038/ncomms6996. PMID 25625704. S2CID 205334234.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "snake (reptile) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia". britannica.com. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ↑ "Snake facts". antiguanracer.org. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ↑ S. Blair Hedges (2008). "At the lower size limit in snakes: two new species of threadsnakes (Squamata: Leptotyphlopidae: Leptotyphlops) from the Lesser Antilles" (PDF). Zootaxa. 1841: 1–30. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1841.1.1. S2CID 15584371. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ Fredriksson G.M. (2005). "Predation on Sun Bears by Reticulated Python in East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo". Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 53 (1): 165–168.

- ↑ Head, Jason J. et al 2009 (2009). "Giant boid snake from the paleocene neotropics reveals hotter past equatorial temperatures". Nature. 457 (7230): 715–718. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..715H. doi:10.1038/nature07671. PMID 19194448. S2CID 4381423. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search