Back Verkoue Afrikaans Erkältung ALS Resfriau común AN زكام Arabic পানীলগা জ্বৰ Assamese Resfriáu común AST Thayjata Aymara Zökəm Azerbaijani زؤکام AZB Һыуыҡ тейеү Bashkir

| Common cold | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cold, acute viral nasopharyngitis, nasopharyngitis, viral rhinitis, rhinopharyngitis, acute coryza, head cold,[1] upper respiratory tract infection (URTI)[2] |

| |

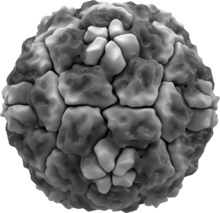

| A representation of the molecular surface of one variant of human rhinovirus | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Cough, sore throat, runny nose, fever[3][4] |

| Complications | Usually none, but occasionally otitis media, sinusitis, pneumonia and sepsis can occur[5] |

| Usual onset | ~2 days from exposure[6] |

| Duration | 1–3 weeks[3][7] |

| Causes | Viral (usually rhinovirus)[8] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms |

| Differential diagnosis | Allergic rhinitis, bronchitis, bronchiolitis,[9] pertussis, sinusitis[5] |

| Prevention | Hand washing, cough etiquette, social distancing, vitamin C[3][10] |

| Treatment | Symptomatic therapy,[3] zinc[11] |

| Medication | NSAIDs[12] |

| Frequency | 2–3 per year (adults) 6–8 per year (children)[13] |

The common cold or the cold is a viral infectious disease of the upper respiratory tract that primarily affects the respiratory mucosa of the nose, throat, sinuses, and larynx.[6][8] Signs and symptoms may appear fewer than two days after exposure to the virus.[6] These may include coughing, sore throat, runny nose, sneezing, headache, and fever.[3][4] People usually recover in seven to ten days,[3] but some symptoms may last up to three weeks.[7] Occasionally, those with other health problems may develop pneumonia.[3]

Well over 200 virus strains are implicated in causing the common cold, with rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, adenoviruses and enteroviruses being the most common.[14] They spread through the air during close contact with infected people or indirectly through contact with objects in the environment, followed by transfer to the mouth or nose.[3] Risk factors include going to child care facilities, not sleeping well, and psychological stress.[6] The symptoms are mostly due to the body's immune response to the infection rather than to tissue destruction by the viruses themselves.[15] The symptoms of influenza are similar to those of a cold, although usually more severe and less likely to include a runny nose.[6][16]

There is no vaccine for the common cold.[3] The primary methods of prevention are hand washing; not touching the eyes, nose or mouth with unwashed hands; and staying away from sick people.[3] Some evidence supports the use of face masks.[10] There is also no cure, but the symptoms can be treated.[3] Zinc may reduce the duration and severity of symptoms if started shortly after the onset of symptoms.[11] Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen may help with pain.[12] Antibiotics, however, should not be used, as all colds are caused by viruses,[17] and there is no good evidence that cough medicines are effective.[6][18]

The common cold is the most frequent infectious disease in humans.[19] Under normal circumstances, the average adult gets two to three colds a year, while the average child may get six to eight.[8][13] Infections occur more commonly during the winter.[3] These infections have existed throughout human history.[20]

- ^ Pramod JR (2008). Textbook of Oral Medicine. Jaypee Brothers Publishers. p. 336. ISBN 978-81-8061-562-7. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016.

- ^ Lee H, Kang B, Hong M, Lee HL, Choi JY, Lee JA (July 2020). "Eunkyosan for the common cold: A PRISMA-compliment systematic review of randomised, controlled trials". Medicine. 99 (31): e21415. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000021415. PMC 7402720. PMID 32756141.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Common Colds: Protect Yourself and Others". CDC. 6 October 2015. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ a b Eccles R (November 2005). "Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 5 (11): 718–25. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70270-X. PMC 7185637. PMID 16253889.

- ^ a b Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ (2014). Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 750. ISBN 978-1-4557-4801-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Allan GM, Arroll B (February 2014). "Prevention and treatment of the common cold: making sense of the evidence". CMAJ. 186 (3): 190–9. doi:10.1503/cmaj.121442. PMC 3928210. PMID 24468694.

- ^ a b Heikkinen T, Järvinen A (January 2003). "The common cold". Lancet. 361 (9351): 51–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12162-9. PMC 7112468. PMID 12517470.

- ^ a b c Arroll B (March 2011). "Common cold". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2011 (3): 1510. PMC 3275147. PMID 21406124.

Common colds are defined as upper respiratory tract infections that affect the predominantly nasal part of the respiratory mucosa

- ^ "Bronchiolitis: Symptoms and Causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ a b Eccles p. 209

- ^ a b "Zinc – Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. 10 July 2019. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

Although studies examining the effect of zinc treatment on cold symptoms have had somewhat conflicting results, overall zinc appears to be beneficial under certain circumstances.... In September of 2007, Caruso and colleagues published a structured review of the effects of zinc lozenges, nasal sprays, and nasal gels on the common cold [69]. Of the 14 randomized, placebo-controlled studies included, 7 (5 using zinc lozenges, 2 using a nasal gel) showed that the zinc treatment had a beneficial effect and 7 (5 using zinc lozenges, 1 using a nasal spray, and 1 using lozenges and a nasal spray) showed no effect. More recently, a Cochrane review concluded that "zinc (lozenges or syrup) is beneficial in reducing the duration and severity of the common cold in healthy people, when taken within 24 hours of onset of symptoms" [73]. The author of another review completed in 2004 also concluded that zinc can reduce the duration and severity of cold symptoms [68]. However, more research is needed to determine the optimal dosage, zinc formulation and duration of treatment before a general recommendation for zinc in the treatment of the common cold can be made [73]. As previously noted, the safety of intranasal zinc has been called into question because of numerous reports of anosmia (loss of smell), in some cases long-lasting or permanent, from the use of zinc-containing nasal gels or sprays [17–19].

- ^ a b Kim SY, Chang YJ, Cho HM, Hwang YW, Moon YS (September 2015). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the common cold". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (9): CD006362. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006362.pub4. PMC 10040208. PMID 26387658.

- ^ a b Simasek M, Blandino DA (February 2007). "Treatment of the common cold". American Family Physician. 75 (4): 515–20. PMID 17323712. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007.

- ^ "Common Cold". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Eccles p. 112

- ^ "Cold Versus Flu". 11 August 2016. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ Harris AM, Hicks LA, Qaseem A (March 2016). "Appropriate Antibiotic Use for Acute Respiratory Tract Infection in Adults: Advice for High-Value Care From the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention". Annals of Internal Medicine. 164 (6): 425–34. doi:10.7326/M15-1840. PMID 26785402. S2CID 746771.

- ^ Malesker MA, Callahan-Lyon P, Ireland B, Irwin RS (November 2017). "Pharmacologic and Nonpharmacologic Treatment for Acute Cough Associated With the Common Cold: CHEST Expert Panel Report". Chest. 152 (5): 1021–1037. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.009. PMC 6026258. PMID 28837801.

A suggestion for the use of zinc lozenges in healthy adults with cough due to common cold was considered by the expert panel. However, due to weak evidence, the potential side effects of zinc, and the relatively benign and common nature of the condition being treated, the panel did not approve inclusion of this suggestion.

- ^ Eccles p. 1

- ^ Eccles R, Weber O (2009). Common cold. Basel: Birkhäuser. p. 3. ISBN 978-3-7643-9894-1. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search