Back مقايضة الائتمان الافتراضي Arabic Kreditin defolt svopu Azerbaijani Credit default swap Czech Credit Default Swap German Συμβάσεις ανταλλαγής κινδύνου αθέτησης Greek Permuta de incumplimiento crediticio Spanish Credit default swap Basque تبادل افول اعتبار Persian Credit default swap Finnish Credit default swap French

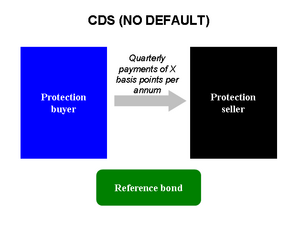

A credit default swap (CDS) is a financial swap agreement that the seller of the CDS will compensate the buyer in the event of a debt default (by the debtor) or other credit event.[1] That is, the seller of the CDS insures the buyer against some reference asset defaulting. The buyer of the CDS makes a series of payments (the CDS "fee" or "spread") to the seller and, in exchange, may expect to receive a payoff if the asset defaults.

In the event of default, the buyer of the credit default swap receives compensation (usually the face value of the loan), and the seller of the CDS takes possession of the defaulted loan or its market value in cash. However, anyone can purchase a CDS, even buyers who do not hold the loan instrument and who have no direct insurable interest in the loan (these are called "naked" CDSs). If there are more CDS contracts outstanding than bonds in existence, a protocol exists to hold a credit event auction. The payment received is often substantially less than the face value of the loan.[2]

Credit default swaps in their current form have existed since the early 1990s and increased in use in the early 2000s. By the end of 2007, the outstanding CDS amount was $62.2 trillion,[3] falling to $26.3 trillion by mid-year 2010[4] and reportedly $25.5[5] trillion in early 2012. CDSs are not traded on an exchange and there is no required reporting of transactions to a government agency.[6] During the 2007–2010 financial crisis the lack of transparency in this large market became a concern to regulators as it could pose a systemic risk.[7][8][9] In March 2010, the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (see Sources of Market Data) announced it would give regulators greater access to its credit default swaps database.[10] There is "$8 trillion notional value outstanding" as of June 2018.[11]

CDS data can be used by financial professionals,[12] regulators, and the media to monitor how the market views credit risk of any entity on which a CDS is available, which can be compared to that provided by the Credit Rating Agencies.

Most CDSs are documented using standard forms drafted by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA), although there are many variants.[7] In addition to the basic, single-name swaps, there are basket default swaps (BDSs), index CDSs, funded CDSs (also called credit-linked notes), as well as loan-only credit default swaps (LCDS). In addition to corporations and governments, the reference entity can include a special purpose vehicle issuing asset-backed securities.[12][13]

Some claim that derivatives such as CDS are potentially dangerous in that they combine priority in bankruptcy with a lack of transparency. A CDS can be unsecured (without collateral) and be at higher risk for a default.

- ^ Azad, C (April 10, 2013). "CDOs Are Back: Will They Lead to Another Financial Crisis". University of Pennsylvania. Wharton. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ Pollack, Lisa (January 5, 2012). "Credit event auctions: Why do they exist?". FT Alphaville. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ "Chart; ISDA Market Survey; Notional amounts outstanding at year-end, all surveyed contracts, 1987–present" (PDF). International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- ^ ISDA 2010 MID-YEAR MARKET SURVEY Archived September 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Latest available a/o 2012-03-01.

- ^ "ISDA: CDS Marketplace :: Market Statistics". Isdacdsmarketplace.com. December 31, 2010. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- ^ Kiff, John; Jennifer Elliott; Elias Kazarian; Jodi Scarlata; Carolyne Spackman (November 2009). "Credit Derivatives: Systemic Risks and Policy Options" (PDF). IMF Working Papers. 09 (254): 1. doi:10.5089/9781451874006.001. S2CID 167560306. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Deutsche Bank Reportwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Sirri Testimonywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Partnoy, Frank; Skeel, David A. Jr. (2007). "The Promise And Perils of Credit Derivatives". University of Cincinnati Law Review. 75. Cincinnati, Ohio: University of Cincinnati: 1019–1051. SSRN 929747.

- ^ "Media Statement: DTCC Policy for Releasing CDS Data to Global Regulators". Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation. March 23, 2010. Archived from the original on April 29, 2010. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- ^ Boyarchenko, Nina (June 2020). "The Long and Short of It: The Post-Crisis Corporate CDS Market" (PDF). newyorkfed.org. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Koresh, Galil; Shapir, Offer Moshe; Amiram, Dan; Ben-Zion, Uri (November 1, 2018). "The Determinants of CDS Spreads" (PDF). Journal of Banking and Finance. 41: 271–282. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.12.005. SSRN 2361872.

- ^ Mengle, David. "Credit Derivatives: An Overview" (PDF). Economic Review (FRB Atlanta), Fourth Quarter 2007. 92 (4). Retrieved January 13, 2016.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search