Back Paryse Kommune Afrikaans Pariser Kommune ALS كومونة باريس Arabic كومونة باريس ARZ Comuña de París AST Paris kommunası Azerbaijani پاریس کوموناسی AZB Парыжская камуна Byelorussian Парижка комуна Bulgarian কমিউন দ্যু পারি Bengali/Bangla

| Paris Commune | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the aftermath of the Siege of Paris in the Franco-Prussian War | |||||||

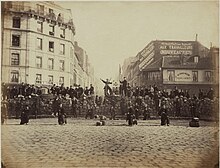

A barricade thrown up by Communard National Guard on 18 March 1871. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

National Guard | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 170,000[1] | 25,000–50,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 877 killed, 6,454 wounded, and 183 missing[3] | 6,667 confirmed killed and buried;[4] unconfirmed estimates from 10 to 15,000[5][6] to as high as 20,000 dead.[7] 43,000 were taken prisoner, and 6,500 to 7,500 self-exiled abroad.[8] | ||||||

The Paris Commune (French: Commune de Paris, pronounced [kɔ.myn də pa.ʁi]) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris from 18 March to 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended Paris, and working-class radicalism grew among its soldiers. Following the establishment of the Third Republic in September 1870 (under French chief executive Adolphe Thiers from February 1871) and the complete defeat of the French Army by the Germans by March 1871, soldiers of the National Guard seized control of the city on March 18. They killed two French army generals and refused to accept the authority of the Third Republic, instead attempting to establish an independent government.

The Commune governed Paris for two months, establishing policies that tended toward a progressive, anti-religious system of their own self-styled socialism, which was an eclectic mix of many 19th-century schools. These policies included the separation of church and state, self-policing, the remission of rent, the abolition of child labor, and the right of employees to take over an enterprise deserted by its owner. All Roman Catholic churches and schools were closed. Feminist, communist, old style social democracy (a mix of reformism and revolutionism), and anarchist currents, among other socialist types, played important roles in the Commune.

The various Communards had little more than two months to achieve their respective goals before the national French Army suppressed the Commune at the end of May during La semaine sanglante ("The Bloody Week") beginning on 21 May 1871. The national forces killed in battle or quickly executed an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 Communards, though one unconfirmed estimate from 1876 put the toll as high as 20,000.[5] In its final days, the Commune executed the Archbishop of Paris, Georges Darboy, and about one hundred hostages, mostly gendarmes and priests. 43,522 Communards were taken prisoner, including 1,054 women. More than half were quickly released. Fifteen thousand were tried, 13,500 of whom were found guilty. Ninety-five were sentenced to death, 251 to forced labor, and 1,169 to deportation (mostly to New Caledonia). Thousands of other Commune members, including several of the leaders, fled abroad, mostly to England, Belgium and Switzerland. All the prisoners and exiles received pardons in 1880 and could return home, where some resumed political careers.[8]

Debates over the policies and outcome of the Commune had significant influence on the ideas of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who described it as the first example of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Engels wrote: "Of late, the Social-Democratic philistine has once more been filled with wholesome terror at the words: Dictatorship of the Proletariat. Well and good, gentlemen, do you want to know what this dictatorship looks like? Look at the Paris Commune. That was the Dictatorship of the Proletariat."[9]

- ^ "Les aspects militaires de la Commune par le colonel Rol-Tanguy" [The military aspects of the Commune by Colonel Rol-Tanguy] (in French). Association des Amies et Amis de la Commune de Paris 1871. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ Milza 2009a, p. 319.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Versailles1875was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Tombs, Robert, "How Bloody was la Semaine sanglante of 1871? A Revision". The Historical Journal, September 2012, vol. 55, issue 03, pp. 619–704.

- ^ a b Audin, Michele (2021). La Semaine Sanglante, Mai 1871, Legendes et Conmptes (in French). Libertalia.

- ^ Rougerie 2014, p. 118.

- ^ Lissagaray 2000, p. 383.

- ^ a b Milza 2009a, pp. 431–432.

- ^ Rougerie 2004, pp. 264–270, citing remarks by Frederick Engels, London, on the 20th anniversary of the Paris Commune, March 18, 1891.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search