Back حق الأرض Arabic Jus soli Byelorussian Ius soli Catalan Ius soli Czech Geburtsortsprinzip German Δίκαιο του εδάφους Greek Jus soli Esperanto Ius soli Spanish Ius soli Estonian اصل خاک Persian

| Legal status of persons |

|---|

|

| Birthright |

| Nationality |

| Immigration |

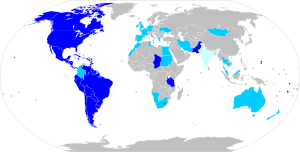

Jus soli (English: /dʒʌs ˈsoʊlaɪ/ juss SOH-ly[citation needed], /juːs ˈsoʊli/ yooss SOH-lee),[1] meaning 'right of the soil', is the right of anyone born in the territory of a state to nationality or citizenship, also commonly referred to as birthright citizenship in some Anglophone countries, is a rule defining a person's nationality based on their birth in the territory of the country.[2][3][4] Jus soli was part of the English common law, in contrast to jus sanguinis, which derives from the Roman law that influenced the civil-law systems of mainland Europe.[5][6]

Jus soli is the predominant rule in the Americas; explanations for this geographical phenomenon include: the establishment of lenient laws by past European colonial powers to entice immigrants from the Old World and displace native populations in the New World, along with the emergence of successful wars of independence movements that widened the definition and granting of citizenship, as a prerequisite to the abolishment of slavery since the 19th century.[7] Outside the Americas, jus soli is rare.[8][9] Since the Twenty-seventh Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland was enacted in 2004, no European country grants nationality based on unconditional or near-unconditional jus soli.[10][11]

Almost all states in Europe, Asia, Africa and Oceania grant nationality at birth based upon the principle of jus sanguinis ("right of blood"), in which nationality is inherited through parents rather than birthplace, or a restricted version of jus soli in which nationality by birthplace is automatic only for the children of certain immigrants.

Jus soli in many cases helps prevent statelessness.[12] Countries that have acceded to the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness are obligated to grant nationality to people born in their territory who would otherwise become stateless persons.[13][a] The American Convention on Human Rights similarly provides that "Every person has the right to the nationality of the state in whose territory he was born if he does not have the right to any other nationality."[12]

- ^ Latin: [juːs ˈsɔliː]; meaning "right of soil" jus soli Archived 8 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine, definition from merriam-webster.com Archived 22 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "International Migration Law No. 34 - Glossary on Migration". International Organization for Migration: 120. 19 June 2019. ISSN 1813-2278.

- ^ Vincent, Andrew (2002). Nationalism and Particularity. Cambridge / New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Solodoch, Omer; Sommer, Udi (2020). "Explaining the birthright citizenship lottery: Longitudinal and cross-national evidence for key determinants". Regulation & Governance. 14: 63–81. doi:10.1111/rego.12197. S2CID 158447458.

- ^ Ayelet Shachar, The Birthright Lottery: Citizenship and Global Inequality (Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 120.

- ^ Rey Koslowski, Migrants and Citizens: Demographic Change in the European State System (Cornell University Press, 2000), p. 77.

- ^ Serhan, Yasmeen; Friedman, Uri (31 October 2018). "America Isn't the 'Only Country' With Birthright Citizenship". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Rotunda, Ronald D. (16 September 2010). "Birthright citizenship benefits the country". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ Smith, Morgan (16 August 2010). "Repeal Birthright Citizenship – and Then What?". Texas Tribune. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ Gilbertson, Greta (1 January 2006). "Citizenship in a Globalized World". Migration Policy Institute. Archived from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ Vink, M.; de Groot, G.R. (2010). Birthright Citizenship: Trends and Regulations in Europe. Comparative Report RSCAS/EUDO-CIT-Comp. 2010/8 (PDF). Florence: EUDO Citizenship Observatory. p. 35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Lung-chu Chen, An Introduction to Contemporary International Law: A Policy-Oriented Perspective (Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 223.

- ^ Ivan Shearer & Brian Opeskin, "Nationality and Statelessness" Foundations of International Migration Law (eds. Brian Opeskin, Richard Perruchoud & Jillyanne Redpath-Cross: Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 99.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search