Back مذبحة تولسا العرقية Arabic Disturbis racials de Tulsa de 1921 Catalan Masakr v Tulse Czech Raceoptøjerne i Tulsa 1921 Danish Massaker von Tulsa German Σφαγή της Τάλσα Greek Rasa tumulto de Tulsa Esperanto Disturbios raciales de Tulsa Spanish Tulsa rassirahutused Estonian Tulsako arrazagatiko sarraskia Basque

| Tulsa race massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of African-American history, mass racial violence in the United States, terrorism in the United States, the nadir of American race relations, and racism against African Americans | |

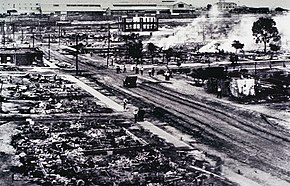

Homes and businesses burned in Greenwood | |

| Location | Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 36°09′34″N 95°59′11″W / 36.1594°N 95.9864°W |

| Date | May 31 – June 1, 1921 |

| Target | Black residents, their homes, businesses, churches, schools, and municipal buildings over a 40 square block area |

Attack type | White supremacist terrorism, pogrom, arson, mass murder |

| Weapons | Guns, explosives, fire[1] |

| Deaths | Total dead and displaced unknown: 36 total; 26 black and 10 white dead (1921 records) 150–200 black and 50 white dead (1921 estimate by W. F. White)[2] 39 confirmed dead, 26 black (1 stillborn) and 13 white;[3] 75–100 to 150–300 estimated dead in total (2001 commission)[4] |

| Injured | 800+ 183 serious injuries[5] Exact number unknown |

| Perpetrators | White mob[6][7][8][9][10][11] |

| Part of a series on the |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

The Tulsa race massacre, also known as the Tulsa race riot or the Black Wall Street massacre,[12] was a two-day-long white supremacist terrorist[13][14] massacre[15] that took place between May 31 and June 1, 1921, when mobs of white residents, some of whom had been appointed as deputies and armed by city government officials,[16] attacked black residents and destroyed homes and businesses of the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The event is considered one of the worst incidents of racial violence in American history.[17][18] The attackers burned and destroyed more than 35 square blocks of the neighborhood—at the time one of the wealthiest black communities in the United States, colloquially known as "Black Wall Street".[19]

More than 800 people were admitted to hospitals, and as many as 6,000 black residents of Tulsa were interned in large facilities, many of them for several days.[20][21] The Oklahoma Bureau of Vital Statistics officially recorded 36 dead.[22] The 2001 Tulsa Reparations Coalition examination of events identified 39 dead, 26 black and 13 white, based on contemporary autopsy reports, death certificates, and other records.[23] The commission gave several estimates ranging from 75 to 300 dead.[24][12]

The massacre began during Memorial Day weekend after 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a black shoeshiner, was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, a white 21-year-old elevator operator in the nearby Drexel Building.[25] He was arrested and rumors that he was to be lynched were spread throughout the city, where a white man named Roy Belton had been lynched the previous year. Upon hearing reports that a mob of hundreds of white men had gathered around the jail where Rowland was being held, a group of 75 black men, some armed, arrived at the jail to protect Rowland. The sheriff persuaded the group to leave the jail, assuring them that he had the situation under control.

The most widely reported and corroborated inciting incident occurred as the group of black men left, when an elderly white man approached O. B. Mann, a black man, and demanded that he hand over his pistol. Mann refused, and the old man attempted to disarm him. A gunshot went off, and then, according to the sheriff's reports, "all hell broke loose".[26] The two groups shot at each other until midnight when the group of black men were greatly outnumbered and forced to retreat to Greenwood. At the end of the exchange of gunfire, 12 people were dead, 10 white and 2 black.[12] Alternatively, another eyewitness account was that the shooting began "down the street from the Courthouse" when black business owners came to the defense of a lone black man being attacked by a group of around six white men.[27] It is possible that the eyewitness did not recognize the fact that this incident was occurring as a part of a rolling gunfight that was already underway. As news of the violence spread throughout the city, mob violence exploded.[2] White rioters invaded Greenwood that night and the next morning, killing men and burning and looting stores and homes. Around noon on June 1, the Oklahoma National Guard imposed martial law, ending the massacre.

About 10,000 black people were left homeless, and the cost of the property damage amounted to more than $1.5 million in real estate and $750,000 in personal property (equivalent to $38.43 million in 2023). By the end of 1922, most of the residents' homes had been rebuilt, but the city and real estate companies refused to compensate them.[28] Many survivors left Tulsa, while residents who chose to stay in the city, regardless of race, largely kept silent about the terror, violence, and resulting losses for decades. The massacre was largely omitted from local, state, and national histories for years.

In 1996, 75 years after the massacre, a bipartisan group in the state legislature authorized the formation of the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. The commission's final report, published in 2001, states that the city had conspired with the racist mob; it recommended a program of reparations to survivors and their descendants.[29] The state passed legislation to establish scholarships for the descendants of survivors, encourage the economic development of Greenwood,[not verified in body] and develop a park in memory of the victims of the massacre in Tulsa. The park was dedicated in 2010. Schools in Oklahoma have been required to teach students about the massacre since 2002,[30] and in 2020, the massacre officially became a part of the Oklahoma school curriculum.[31]

- ^ Oklahoma Commission 2001, p. 196.

- ^ a b National Endowment for the Humanities (June 18, 1921). "The broad ax. [volume] (Salt Lake City, Utah) 1895–19??, June 18, 1921, Image 1". The Broad Ax. ISSN 2163-7202. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ Oklahoma Commission 2001, p. 116.

- ^ Oklahoma Commission 2001, p. 124.

- ^ Willows 1921, p. [page needed].

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Cleaverwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Gurleywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lutherwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Rooney, Lt. Col. L. J. F.; Daley, Charles (June 3, 1921). "Letter from Lieutenant Colonel L. J. F. Rooney and Charles Daley of the Inspector General's Department to the Adjutant General, June 3, 1921". Archived from the original on December 3, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ Franklin 1931, pp. 8, 10.

- ^ Oklahoma Commission 2001, pp. 193, 196.

- ^ a b c White, Walter F. (August 23, 2001). "Tulsa, 1921". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ "Tulsa race massacre at 100: an act of terrorism America tried to forget". The Guardian. May 31, 2021. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ II, Herbert G. Ruffin (May 27, 2021). "We Can Best Honor Our Past by Not Burying It: The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921". Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ "Tulsa race massacre of 1921 | Commission, Facts, & Books". Britannica. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

HBO-Watchmenwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ellsworth, Scott (2009). "Tulsa Race Riot". The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ Parshina-Kottas, Yuliya; Singhvi, Anjali; Burch, Audra D. S.; Griggs, Troy; Gröndahl, Mika; Huang, Lingdong; Wallace, Tim; White, Jeremy; Williams, Josh (May 24, 2021). "What the Tulsa Race Massacre Destroyed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Huddleston Jr, Tom (July 4, 2020). "'Black Wall Street': The history of the wealthy black community and the massacre perpetrated there". CNBC. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

messerbellwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Messer, Chris M.; Beamon, Krystal; Bell, Patricia A. (2013). "The Tulsa Riot of 1921: Collective Violence and Racial Frames". The Western Journal of Black Studies. 37 (1): 50–59. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Various (February 21, 2001). Report on Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. p. 123. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

(...) the official count of 36 (...)

- ^ Oklahoma Commission 2001, p. 114.

- ^ Oklahoma Commission 2001, pp. 13, 23.

- ^ Hopkins, Randy (July 6, 2023). "The Notorious Sarah Page". CfPS. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

MADIGANwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Clark, Nia (January 21, 2020). "A black Wall Street Legend - The Story of Peg Leg Taylor and the Legacy of Trauma". Dreams of Black Wall Street. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Luckerson, Victor (June 28, 2018). "Black Wall Street: The African American Haven That Burned and Then Rose From the Ashes". The Ringer. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ Oklahoma Commission 2001, p. [page needed].

- ^ Miller, Ken (February 20, 2020). "Curriculum being developed to teach Tulsa race massacre". Associated Press. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ Connor, Jay (2020). "The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Will Officially Become a Part of the Oklahoma School Curriculum Beginning in the Fall". The Root. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search