Back كودكس أزتيكي Arabic Còdexs mexiques Catalan Aztekencodices German Códices mexicas Spanish Kodex mexikak Basque دفترنامههای آزتک Persian Asteekkien koodeksit Finnish Codex aztèque French קודקס אצטקי HE Kodeks-kodeks Aztek ID

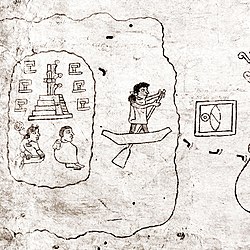

Aztec codices (Nahuatl languages: Mēxihcatl āmoxtli Nahuatl pronunciation: [meːˈʃiʔkatɬ aːˈmoʃtɬi], sing. codex) are Mesoamerican manuscripts made by the pre-Columbian Aztec, and their Nahuatl-speaking descendants during the colonial period in Mexico.[1] Most of their content is pictorial in nature and they come from the multiple indigenous groups from before and after Spanish contact and differences in styles indicate regional differences. The types of information in manuscripts fall into several categories: calendrical, historical, genealogical, cartographic, economic/tribute, economic/census and cadastral, and economic/property plans. Codex Mendoza and the Florentine Codex are among the important colonial-era codices for which there are translations available in English.

- ^ Batalla, Juan José (2016-12-05). "The Historical Sources: Codices and Chronicles". In Nichols, Deborah L.; Rodríguez-Alegría, Enrique (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 29–40. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199341962.013.30.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search