Back বলীপ্রতিপদ Bengali/Bangla ಬಲಿಪಾಡ್ಯ Kannada बलिप्रतिपदा Marathi బలి పాడ్యమి Tegulu بالی پرتیپدا Urdu

| Bali-pratipada | |

|---|---|

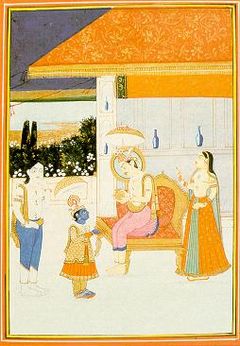

Vamana (blue faced dwarf) in the court of King Bali (Raja Bali, right seated) seeking alms | |

| Also called | Bali Padwa (Maharashtra), Bali Padyami (Karnataka), Barlaj (Himachal Pradesh), Raja Bali (Jammu), Gujarati New Year (Bestu Varas), Marwari New Year |

| Observed by | Hindus |

| Type | Hindu |

| Observances | Festival of lights as celebration of return of Mahabali to earth for a day |

| Date | Kartika 1 (amanta tradition) Kartika 16 (purnimanta tradition) |

| 2023 date | 14 November |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Diwali |

Hindu festival dates The Hindu calendar is lunisolar but most festival dates are specified using the lunar portion of the calendar. A lunar day is uniquely identified by three calendar elements: māsa (lunar month), pakṣa (lunar fortnight) and tithi (lunar day). Furthermore, when specifying the masa, one of two traditions are applicable, viz. amānta / pūrṇimānta. If a festival falls in the waning phase of the moon, these two traditions identify the same lunar day as falling in two different (but successive) masa. A lunar year is shorter than a solar year by about eleven days. As a result, most Hindu festivals occur on different days in successive years on the Gregorian calendar. | |

Balipratipada (Bali-pratipadā), also called as Bali-Padyami, Padva, Virapratipada or Dyutapratipada, is the fourth day of Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights.[2][3] It is celebrated in honour of the notional return of the daitya-king Bali (Mahabali) to earth. Balipratipada falls in the Gregorian calendar months of October or November. It is the first (or 16th) day of the Hindu month of Kartika and is the first day of its bright lunar fortnight.[4][5][6] In many parts of India such as Gujarat and Rajasthan, it is the regional traditional New Year Day in Vikram Samvat and also called the Bestu Varas or Varsha Pratipada.[7][8] This is the half amongst the three and a half Muhūrtas in a year.

Balipratipada is an ancient festival. The earliest mention of Bali's story being acted out in dramas and poetry of ancient India is found in the c. 2nd-century BCE Mahābhāṣya of Patanjali on Panini's Astadhyayi 3.1.26.[3] The festival has links to the Vedic era sura-asura Samudra Manthana that revealed goddess Lakshmi and where Bali was the king of the asuras.[9] The festivities find mention in the Mahabharata,[3] the Ramayana,[10] and several major Puranas, such as the Brahma Purana, Kurma Purana, Matsya Purana and others.[3]

Balipratipada commemorates the annual return of Bali to earth and the victory of Vamana, the dwarf avatar of the god Vishnu. It marks the victory of Vishnu over Bali and all asuras, through his metamorphosis into Vamana-Trivikrama.[2] At the time of his defeat, Bali was already a Vishnu-devotee and a benevolent ruler over a peaceful, prosperous kingdom.[3] Vishnu's victory over Bali using "three steps" ended the war.[4][10] According to Hindu scriptures, Bali asked for and was granted the boon by Vishnu, whereby he returns to earth once a year when he will be remembered and worshipped, and reincarnate in a future birth as Indra.[3][11][12]

Balipratipada or Padva is traditionally celebrated with decorating the floor with colorful images of Bali – sometimes with his wife Vindyavati,[8] of nature's abundance, a shared feast, community events and sports, drama or poetry sessions. In some regions, rice and food offerings are made to recently dead ancestors (shraddha), or the horns of cows and bulls are decorated, people gamble, or icons of Vishnu avatars are created and garlanded in addition.[3][12][8][13]

- ^ BSE India, India Financial Market Holidays (2020)

- ^ a b Manu Belur Bhagavan; Eleanor Zelliot; Anne Feldhaus (2008). 'Speaking Truth to Power': Religion, Caste, and the Subaltern Question in India. Oxford University Press. pp. 94–103. ISBN 978-0-19-569305-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g PV Kane (1958). History of Dharmasastra, Volume 5 Part 1. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. pp. 201–206.

- ^ a b Ramakrishna, H. A.; H. L. Nage Gowda (1998). Essentials of Karnataka folklore: a compendium. Karnataka Janapada Parishat. p. 258. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Devi, Konduri Sarojini (1990). Religion in Vijayanagara Empire. Sterling Publishers. p. 277. ISBN 9788120711679. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Hebbar, B. N. (2005). The Śrī-Kṛṣṇa Temple at Uḍupi: the historical and spiritual center of the ... Bharatiya Granth Niketan. p. 237. ISBN 978-81-89211-04-2. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Bestu Varas: For Gujratis celebrations continue the day after Diwali too, The Times of India (October 25, 2011)

- ^ a b c K. Gnanambal (1969). Festivals of India. Anthropological Survey of India. pp. 5–17.

- ^ Tracy Pintchman (2005). Guests at God's Wedding: Celebrating Kartik among the Women of Benares. State University of New York Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-7914-6595-0.

- ^ a b Narayan, R.K (1977). The Ramayana: a shortened modern prose version of the Indian epic. Penguin Classics. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-0-14-018700-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Yves Bonnefoy (1993). Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-226-06456-7.

- ^ a b Joanna Gottfried Williams (1981). Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India. BRILL. p. 70. ISBN 90-04-06498-2.

- ^ J. P. Vaswani (2017). Dasavatara. Jaico Publishing House. pp. 73–77. ISBN 978-93-86867-18-6.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search