Back مبيضة بيضاء Arabic مبيضه بيضاء ARZ Candida albicans Bulgarian Candida albicans BJN Candida albicans BS Candida albicans Catalan Candida albicans CEB کاندیدا ئەلبیکانس CKB Candida albicans Czech Candida albicans Danish

| Candida albicans | |

|---|---|

| |

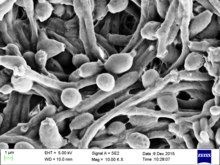

| Candida albicans visualized using scanning electron microscopy. Note the abundant hyphal mass. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Saccharomycetes |

| Order: | Saccharomycetales |

| Family: | Saccharomycetaceae |

| Genus: | Candida |

| Species: | C. albicans

|

| Binomial name | |

| Candida albicans (C.-P. Robin) Berkhout (1923)

| |

| Synonyms | |

Candida albicans is an opportunistic pathogenic yeast[5] that is a common member of the human gut flora. It can also survive outside the human body.[6][7] It is detected in the gastrointestinal tract and mouth in 40–60% of healthy adults.[8][9] It is usually a commensal organism, but it can become pathogenic in immunocompromised individuals under a variety of conditions.[9][10] It is one of the few species of the genus Candida that cause the human infection candidiasis, which results from an overgrowth of the fungus.[9][10] Candidiasis is, for example, often observed in HIV-infected patients.[11] C. albicans is the most common fungal species isolated from biofilms either formed on (permanent) implanted medical devices or on human tissue.[12][13] C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. glabrata are together responsible for 50–90% of all cases of candidiasis in humans.[10][14][15] A mortality rate of 40% has been reported for patients with systemic candidiasis due to C. albicans.[16] By one estimate, invasive candidiasis contracted in a hospital causes 2,800 to 11,200 deaths yearly in the US.[14] Nevertheless, these numbers may not truly reflect the true extent of damage this organism causes, given new studies indicating that C. albicans can cross the blood–brain barrier in mice.[17][18]

C. albicans is commonly used as a model organism for fungal pathogens.[19] It is generally referred to as a dimorphic fungus since it grows both as yeast and filamentous cells. However, it has several different morphological phenotypes including opaque, GUT, and pseudohyphal forms.[20][21] C. albicans was for a long time considered an obligate diploid organism without a haploid stage. This is, however, not the case. Next to a haploid stage C. albicans can also exist in a tetraploid stage. The latter is formed when diploid C. albicans cells mate when they are in the opaque form.[22] The diploid genome size is approximately 29 Mb, and up to 70% of the protein coding genes have not yet been characterized.[23] C. albicans is easily cultured in the lab and can be studied both in vivo and in vitro. Depending on the media different studies can be done as the media influences the morphological state of C. albicans. A special type of medium is CHROMagar Candida, which can be used to identify different Candida species.[24][25]

- ^ Candida albicans at NCBI Taxonomy browser Archived 2018-12-15 at the Wayback Machine, url accessed 2006-12-26

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

The yeastswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Saygin D, Tabib T, Bittar HE, Valenzi E, Sembrat J, Chan SY, et al. (May 1952). "Transcriptional profiling of lung cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension". Pulmonary Circulation. 10 (1): 137–164. doi:10.2307/2394509. JSTOR 2394509. PMC 7052475. PMID 32166015.

- ^ "Synonymy of Candida albicans". speciesfungorum.org. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Gow NA, Yadav B (August 2017). "Microbe Profile: Candida albicans: a shape-changing, opportunistic pathogenic fungus of humans". Microbiology. 163 (8): 1145–1147. doi:10.1099/mic.0.000499. hdl:2164/12360. PMID 28809155.

- ^ Bensasson D, Dicks J, Ludwig JM, Bond CJ, Elliston A, Roberts IN, James SA (January 2019). "Diverse Lineages of Candida albicans Live on Old Oaks". Genetics. 211 (1): 277–288. doi:10.1534/genetics.118.301482. PMC 6325710. PMID 30463870.

- ^ Odds FC (1988). Candida and Candidosis: A Review and Bibliography (2nd ed.). London; Philadelphia: Bailliere Tindall. ISBN 978-0702012655.

- ^ Kerawala C, Newlands C, eds. (2010). Oral and maxillofacial surgery. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 446, 447. ISBN 978-0-19-920483-0.

- ^ a b c Erdogan A, Rao SS (April 2015). "Small intestinal fungal overgrowth". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 17 (4): 16. doi:10.1007/s11894-015-0436-2. PMID 25786900. S2CID 3098136.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

pmid24789109was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Calderonewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Kumamoto CA (December 2002). "Candida biofilms". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 5 (6): 608–611. doi:10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00371-5. PMID 12457706.

- ^ Donlan RM (October 2001). "Biofilm formation: a clinically relevant microbiological process". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 33 (8): 1387–1392. doi:10.1086/322972. PMID 11565080.

- ^ a b Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ (January 2007). "Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 20 (1): 133–163. doi:10.1128/CMR.00029-06. PMC 1797637. PMID 17223626.

- ^ Schlecht LM, Peters BM, Krom BP, Freiberg JA, Hänsch GM, Filler SG, et al. (January 2015). "Systemic Staphylococcus aureus infection mediated by Candida albicans hyphal invasion of mucosal tissue". Microbiology. 161 (Pt 1): 168–181. doi:10.1099/mic.0.083485-0. PMC 4274785. PMID 25332378.

- ^ Singh R, Chakrabarti A (2017). "Invasive Candidiasis in the Southeast-Asian Region". In Prasad R (ed.). Candida albicans: Cellular and Molecular Biology (2 ed.). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG. p. 27. ISBN 978-3-319-50408-7.

- ^ Wu Y, Du S, Johnson JL, Tung HY, Landers CT, Liu Y, et al. (January 2019). "Microglia and amyloid precursor protein coordinate control of transient Candida cerebritis with memory deficits". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 58. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10...58W. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07991-4. PMC 6320369. PMID 30610193.

- ^ "Fungi cause brain infection and impair memory in mice". Archived from the original on 2023-11-20. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- ^ Kabir MA, Hussain MA, Ahmad Z (2012). "Candida albicans: A Model Organism for Studying Fungal Pathogens". ISRN Microbiology. 2012: 538694. doi:10.5402/2012/538694. PMC 3671685. PMID 23762753.

- ^ Kadosh D (December 2019). "Regulatory mechanisms controlling morphology and pathogenesis in Candida albicans". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 52: 27–34. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2019.04.005. PMC 6874724. PMID 31129557.

- ^ Basso V, d'Enfert C, Znaidi S, Bachellier-Bassi S (2019). "From Genes to Networks: The Regulatory Circuitry Controlling Candida albicans Morphogenesis". Fungal Physiology and Immunopathogenesis. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 422. pp. 61–99. doi:10.1007/82_2018_144. ISBN 978-3-030-30236-8. PMID 30368597.

- ^ Hickman MA, Zeng G, Forche A, Hirakawa MP, Abbey D, Harrison BD, et al. (February 2013). "The 'obligate diploid' Candida albicans forms mating-competent haploids". Nature. 494 (7435): 55–59. Bibcode:2013Natur.494...55H. doi:10.1038/nature11865. PMC 3583542. PMID 23364695.

- ^ "Candida albicans SC5314 Genome Snapshot/Overview". www.candidagenome.org. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ Sevilla MJ, Odds FC (November 1986). "Development of Candida albicans hyphae in different growth media--variations in growth rates, cell dimensions and timing of morphogenetic events". Journal of General Microbiology. 132 (11): 3083–3088. doi:10.1099/00221287-132-11-3083. PMID 3305781.

- ^ Odds FC, Bernaerts R (August 1994). "CHROMagar Candida, a new differential isolation medium for presumptive identification of clinically important Candida species". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 32 (8): 1923–1929. doi:10.1128/JCM.32.8.1923-1929.1994. PMC 263904. PMID 7989544.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search