Back Dehidrasie Afrikaans Dehydratation (Medizin) ALS تجفاف Arabic Deshidratación AST دهیدراتاسیون AZB Дехидратация Bulgarian পানিশূন্যতা Bengali/Bangla Dehidracija BS Deshidratació Catalan Dehydratace Czech

| Dehydration | |

|---|---|

| |

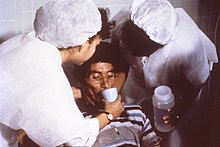

| Nurses encourage a patient to drink an oral rehydration solution to treat the combination of dehydration and hypovolemia secondary to cholera. Cholera leads to GI loss of both excess free water (dehydration) and sodium (hence ECF volume depletion—hypovolemia). | |

| Specialty | Critical care medicine |

| Symptoms | Increased thirst, tiredness, decreased urine, dizziness, headaches, and confusion[1] |

| Complications | Low blood volume shock (hypovolemic shock), coma, seizures, urinary tract infection, kidney disease, heatstroke, hypernatremia, metabolic disease,[1] hypertension.[2] |

| Causes | Loss of body water |

| Risk factors | Physical water scarcity, heatwaves, disease (most commonly from diseases that cause vomiting and/or diarrhea), exercise |

| Treatment | Drinking clean water |

| Medication | Saline |

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water,[3] with an accompanying disruption of metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds free water intake, usually due to exercise, disease, or high environmental temperature. Mild dehydration can also be caused by immersion diuresis, which may increase risk of decompression sickness in divers.

Most people can tolerate a 3-4% decrease in total body water without difficulty or adverse health effects. A 5-8% decrease can cause fatigue and dizziness. Loss of over 10% of total body water can cause physical and mental deterioration, accompanied by severe thirst. Death occurs at a loss of between 15 and 25% of the body water.[4] Mild dehydration is characterized by thirst and general discomfort and is usually resolved with oral rehydration.

Dehydration can cause hypernatremia (high levels of sodium ions in the blood) and is distinct from hypovolemia (loss of blood volume, particularly blood plasma).

Chronic dehydration can contribute to the formation of kidney stones as well as the development of chronic kidney disease.[5][6]

- ^ a b "Dehydration - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ Ahmed M. El-Sharkawy; Opinder Sahota; Dileep N. Lobo. "Acute and chronic effects of hydration status on health". academic.oup.com. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Mange K, Matsuura D, Cizman B, Soto H, Ziyadeh FN, Goldfarb S, Neilson EG (November 1997). "Language guiding therapy: the case of dehydration versus volume depletion". Annals of Internal Medicine. 127 (9): 848–53. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00020. PMID 9382413. S2CID 29854540.

- ^ Ashcroft F, Life Without Water in Life at the Extremes. Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2000, 134-138.

- ^ Seal, Adam D.; Suh, Hyun-Gyu; Jansen, Lisa T.; Summers, LynnDee G.; Kavouras, Stavros A. (2019). "Hydration and Health". Analysis in Nutrition Research. Elsevier. pp. 299–319. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814556-2.00011-7. ISBN 978-0-12-814556-2.

- ^ Clark, William F.; Sontrop, Jessica M.; Huang, Shi-Han; Moist, Louise; Bouby, Nadine; Bankir, Lise (2016). "Hydration and Chronic Kidney Disease Progression: A Critical Review of the Evidence". American Journal of Nephrology. 43 (4): 281–292. doi:10.1159/000445959. ISSN 0250-8095.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search