Back حمل خارج الرحم Arabic Пазаматачная цяжарнасць Byelorussian Извънматочна бременност Bulgarian Vanmaterična trudnoća BS Embaràs ectòpic Catalan Mimoděložní těhotenství Czech Extrauteringravidität German Έκτοπη κύηση Greek Ektopia gravedeco Esperanto Embarazo ectópico Spanish

| Ectopic pregnancy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | EP, eccyesis, extrauterine pregnancy, EUP, tubal pregnancy (when in fallopian tube) |

| |

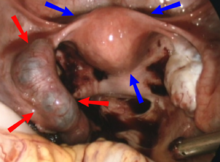

| Laparoscopic view, looking down at the uterus (marked by blue arrows). In the left fallopian tube, there is an ectopic pregnancy and bleeding (marked by red arrows). The right tube is normal. | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics and Gynaecology |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding[1] |

| Risk factors | Pelvic inflammatory disease, tobacco smoking, prior tubal surgery, history of infertility, use of assisted reproductive technology[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests for human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), ultrasound[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Miscarriage, ovarian torsion, acute appendicitis,[1] corpus luteum cyst rupture[3] |

| Treatment | methotrexate, surgery[2] |

| Prognosis | Mortality 0.2% (developed world), 2% (developing world)[4] |

| Frequency | ~1.5% of pregnancies (developed world)[5] |

Ectopic pregnancy is a complication of pregnancy in which the embryo attaches outside the uterus.[5] Signs and symptoms classically include abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding, but fewer than 50 percent of affected women have both of these symptoms.[1] The pain may be described as sharp, dull, or crampy.[1] Pain may also spread to the shoulder if bleeding into the abdomen has occurred.[1] Severe bleeding may result in a fast heart rate, fainting, or shock.[5][1] With very rare exceptions, the fetus is unable to survive.[6]

Overall, ectopic pregnancies annually affect less than 2% of pregnancies worldwide.[5] Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include pelvic inflammatory disease, often due to chlamydia infection; tobacco smoking; endometriosis; prior tubal surgery; a history of infertility; and the use of assisted reproductive technology.[2] Those who have previously had an ectopic pregnancy are at much higher risk of having another one.[2] Most ectopic pregnancies (90%) occur in the fallopian tube, which are known as tubal pregnancies,[2] but implantation can also occur on the cervix, ovaries, caesarean scar, or within the abdomen.[1] Detection of ectopic pregnancy is typically by blood tests for human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and ultrasound.[1] This may require testing on more than one occasion.[1] Other causes of similar symptoms include: miscarriage, ovarian torsion, and acute appendicitis.[1]

Prevention is by decreasing risk factors such as chlamydia infections through screening and treatment.[7] While some ectopic pregnancies will miscarry without treatment,[2] the standard treatment for ectopic pregnancy is a procedure to either remove the embryo from the fallopian tube or to remove the fallopian tube all together. The use of the medication methotrexate works as well as surgery in some cases.[2] Specifically it works well when the beta-HCG is low and the size of the ectopic is small.[2] Surgery such as a salpingectomy is still typically recommended if the tube has ruptured, there is a fetal heartbeat, or the woman's vital signs are unstable.[2] The surgery may be laparoscopic or through a larger incision, known as a laparotomy.[5] Maternal morbidity and mortality are reduced with treatment.[2]

The rate of ectopic pregnancy is about 11 to 20 per 1,000 live births in developed countries, though it may be as high as 4% among those using assisted reproductive technology.[5] It is the most common cause of death among women during the first trimester at approximately 6-13% of the total.[2] In the developed world outcomes have improved while in the developing world they often remain poor.[7] The risk of death among those in the developed world is between 0.1 and 0.3 percent while in the developing world it is between one and three percent.[4] The first known description of an ectopic pregnancy is by Al-Zahrawi in the 11th century.[7] The word "ectopic" means "out of place".[8]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Crochet JR, Bastian LA, Chireau MV (April 2013). "Does this woman have an ectopic pregnancy?: the rational clinical examination systematic review". JAMA. 309 (16): 1722–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.3914. PMID 23613077. S2CID 205049738.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Cecchino GN, Araujo Júnior E, Elito Júnior J (September 2014). "Methotrexate for ectopic pregnancy: when and how". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 290 (3): 417–23. doi:10.1007/s00404-014-3266-9. PMID 24791968. S2CID 26727563.

- ^ Bauman, Renato; Horvat, Gordana (December 2018). "MANAGEMENT OF RUPTURED CORPUS LUTEUM WITH HEMOPERITONEUM IN EARLY PREGNANCY – A CASE REPORT". Acta Clinica Croatica. 57 (4): 785–788. doi:10.20471/acc.2018.57.04.24. PMC 6544092. PMID 31168219.

- ^ a b Mignini L (26 September 2007). "Interventions for tubal ectopic pregnancy". who.int. The WHO Reproductive Health Library. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Kirk E, Bottomley C, Bourne T (2014). "Diagnosing ectopic pregnancy and current concepts in the management of pregnancy of unknown location". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (2): 250–61. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt047. PMID 24101604.

- ^ Zhang J, Li F, Sheng Q (2008). "Full-term abdominal pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature". Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 65 (2): 139–41. doi:10.1159/000110015. PMID 17957101. S2CID 35923100.

- ^ a b c Nama V, Manyonda I (April 2009). "Tubal ectopic pregnancy: diagnosis and management". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 279 (4): 443–53. doi:10.1007/s00404-008-0731-3. PMID 18665380. S2CID 22538462.

- ^ Cornog MW (1998). Merriam-Webster's vocabulary uilder. Springfield, Mass.: Merriam-Webster. p. 313. ISBN 9780877799108. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search