Back منحنى إهليلجي Arabic Эліптычная крывая Byelorussian Corba el·líptica Catalan Eliptická křivka Czech Эллипсла йĕр CV Elliptisk kurve Danish Elliptische Kurve German Ελλειπτική καμπύλη Greek Elipsa kurbo Esperanto Curva elíptica Spanish

(For (a, b) = (0, 0) the function is not smooth and therefore not an elliptic curve.)

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

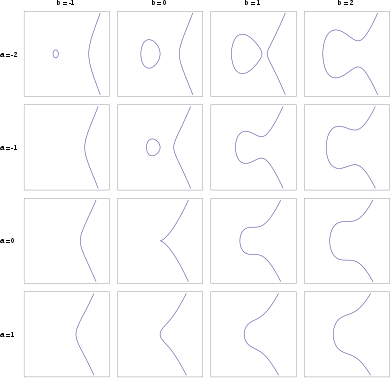

In mathematics, an elliptic curve is a smooth, projective, algebraic curve of genus one, on which there is a specified point O. An elliptic curve is defined over a field K and describes points in K2, the Cartesian product of K with itself. If the field's characteristic is different from 2 and 3, then the curve can be described as a plane algebraic curve which consists of solutions (x, y) for:

for some coefficients a and b in K. The curve is required to be non-singular, which means that the curve has no cusps or self-intersections. (This is equivalent to the condition 4a3 + 27b2 ≠ 0, that is, being square-free in x.) It is always understood that the curve is really sitting in the projective plane, with the point O being the unique point at infinity. Many sources define an elliptic curve to be simply a curve given by an equation of this form. (When the coefficient field has characteristic 2 or 3, the above equation is not quite general enough to include all non-singular cubic curves; see § Elliptic curves over a general field below.)

An elliptic curve is an abelian variety – that is, it has a group law defined algebraically, with respect to which it is an abelian group – and O serves as the identity element.

If y2 = P(x), where P is any polynomial of degree three in x with no repeated roots, the solution set is a nonsingular plane curve of genus one, an elliptic curve. If P has degree four and is square-free this equation again describes a plane curve of genus one; however, it has no natural choice of identity element. More generally, any algebraic curve of genus one, for example the intersection of two quadric surfaces embedded in three-dimensional projective space, is called an elliptic curve, provided that it is equipped with a marked point to act as the identity.

Using the theory of elliptic functions, it can be shown that elliptic curves defined over the complex numbers correspond to embeddings of the torus into the complex projective plane. The torus is also an abelian group, and this correspondence is also a group isomorphism.

Elliptic curves are especially important in number theory, and constitute a major area of current research; for example, they were used in Andrew Wiles's proof of Fermat's Last Theorem. They also find applications in elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) and integer factorization.

An elliptic curve is not an ellipse in the sense of a projective conic, which has genus zero: see elliptic integral for the origin of the term. However, there is a natural representation of real elliptic curves with shape invariant j ≥ 1 as ellipses in the hyperbolic plane . Specifically, the intersections of the Minkowski hyperboloid with quadric surfaces characterized by a certain constant-angle property produce the Steiner ellipses in (generated by orientation-preserving collineations). Further, the orthogonal trajectories of these ellipses comprise the elliptic curves with j ≤ 1, and any ellipse in described as a locus relative to two foci is uniquely the elliptic curve sum of two Steiner ellipses, obtained by adding the pairs of intersections on each orthogonal trajectory. Here, the vertex of the hyperboloid serves as the identity on each trajectory curve.[1]

Topologically, a complex elliptic curve is a torus, while a complex ellipse is a sphere.

- ^ Sarli, J. (2012). "Conics in the hyperbolic plane intrinsic to the collineation group". J. Geom. 103: 131–148. doi:10.1007/s00022-012-0115-5. S2CID 119588289.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search