Back تأريخ الثورة الفرنسية Arabic Ιστοριογραφία της Γαλλικής Επανάστασης Greek Historiografía de la Revolución francesa Spanish Historiographie de la Révolution française French Историография Великой французской революции Russian

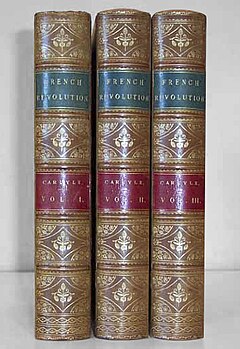

The historiography of the French Revolution stretches back over two hundred years.

Contemporary and 19th-century writings on the Revolution were mainly divided along ideological lines, with conservative historians condemning the Revolution, liberals praising the Revolution of 1789, and radicals defending the democratic and republican values of 1793. By the 20th-century, revolutionary history had become professionalised, with scholars paying more attention to the critical analysis of primary sources from public archives.

From the late 1920s to the 1960s, social and economic interpretations of the Revolution, often from a Marxist perspective, dominated the historiography of the Revolution in France. This trend was challenged by revisionist historians in the 1960s who argued that class conflict was not a major determinant of the course of the Revolution and that political expediency and historical contingency often played a greater role than social factors.

In the 21st-century, no single explanatory model has gained widespread support. The historiography of the revolution has become more diversified, exploring areas such as cultural histories, gender relations, regional histories, visual representations, transnational interpretations, and decolonisation.[1][2] Nevertheless, there persists a very widespread agreement that the French Revolution was the watershed between the premodern and modern eras of Western history.[1]

- ^ a b Spang (2003).

- ^ Bell (2004).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search