Back تاريخ الأستراليين الأصليين Arabic Historia dos indíxenas de Australia Galician História dos indígenas australianos Portuguese

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Australia |

|---|

|

|

|

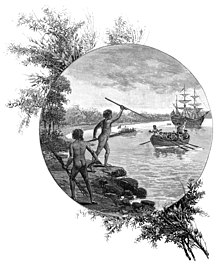

The history of Indigenous Australians began 50,000 to 65,000 years ago when humans first populated the Australian continental landmasses.[1][2][3][4] This article covers the history of Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander peoples, two broadly defined groups which each include other sub-groups defined by language and culture. Human habitation of the Australian continent began with the migration of the ancestors of today's Aboriginal Australians by land bridges and short sea crossings from what is now Southeast Asia.[5] The Aboriginal people spread throughout the continent, adapting to diverse environments and climate change to develop one of the oldest continuous cultures on Earth.[6][7]

At the time of first European contact, estimates of the Aboriginal population range from 300,000 to one million.[8][9][10] They were complex hunter-gatherers with diverse economies and societies. There were about 600 tribes or nations and 250 languages with various dialects.[11][12] Certain groups engaged in fire-stick farming[13]and fish farming,[14] while they built semi-permanent shelters.[15][16] The extent to which some groups engaged in agriculture is controversial.[17][18][19]

The Torres Strait Islander people first settled their islands around 4,000 years ago. Culturally and linguistically distinct from mainland Aboriginal peoples, they were seafarers and obtained their livelihood from seasonal horticulture and the resources of their reefs and seas. Agriculture also developed on some islands. Villages had appeared in their areas by the 14th century.[20][21]

The British Empire established a penal colony at Botany Bay in 1788. In the 150 years that followed, the number of Indigenous Australians fell sharply due to introduced diseases and violent conflict with the colonists. From the 1930s, the Indigenous population began to recover and Indigenous communities founded organisations to advocate for their rights. From the 1960s, Indigenous people won the right to vote in federal and state elections, and some won the return of parts of their traditional lands. In 1992, the High Court of Australia, in the Mabo Case, found that Indigenous native title rights existed in common law. By 2021, Indigenous Australians had exclusive or shared title to about 54% of the Australian land mass.[22]

From 1971 to 2006, Indigenous employment, median incomes, home ownership, education and life expectancy all improved, although they remained well below the level for those who were not indigenous.[23] Since 2008, successive Australian governments have launched policies aimed at reducing Indigenous disadvantage in education, employment, literacy and child mortality. However, by 2023 Indigenous people still experienced entrenched inequality.[24] In October 2023, the Australian people, in a referendum, voted against a constitutional amendment to establish an Indigenous advisory body to government.

- ^ Williams, Martin A. J.; Spooner, Nigel A.; McDonnell, Kathryn; O'Connell, James F. (January 2021). "Identifying disturbance in archaeological sites in tropical northern Australia: Implications for previously proposed 65,000-year continental occupation date". Geoarchaeology. 36 (1): 92–108. Bibcode:2021Gearc..36...92W. doi:10.1002/gea.21822. ISSN 0883-6353. S2CID 225321249. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Clarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; Marwick, Ben; Fullagar, Richard; Wallis, Lynley; Smith, Mike; Roberts, Richard G.; Hayes, Elspeth; Lowe, Kelsey; Carah, Xavier; Florin, S. Anna; McNeil, Jessica; Cox, Delyth; Arnold, Lee J.; Hua, Quan; Huntley, Jillian; Brand, Helen E. A.; Manne, Tiina; Fairbairn, Andrew; Shulmeister, James; Lyle, Lindsey; Salinas, Makiah; Page, Mara; Connell, Kate; Park, Gayoung; Norman, Kasih; Murphy, Tessa; Pardoe, Colin (2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago". Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C. doi:10.1038/nature22968. hdl:2440/107043. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28726833. S2CID 205257212.

- ^ Veth & O'Connor 2013, p. 19.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M.; Durrani, Nadia (2018). People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory. Taylor & Francis. pp. 250–253. ISBN 978-1-3517-5764-5. Archived from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Stephen (2013). Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World. Little, Brown Book Group. pp. 111–. ISBN 978-1-7803-3753-1. Archived from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ Flood 2019, p. 161.

- ^ Malaspinas, Anna-Sapfo; et al. (21 September 2016). "A genomic history of Aboriginal Australia". Nature. 538 (7624). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 207–214. Bibcode:2016Natur.538..207M. doi:10.1038/nature18299. hdl:10754/622366. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 27654914.

- ^ "1301.0 – Year Book Australia, 2002" Archived 16 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 25 January 2002.

- ^ McCalman, Janet; Kipen, Rebecca (2013). "Population and health". The Cambridge History of Australia, volume 1. p. 294.

- ^ Flood 2019, pp. 30–35.

- ^ Flood 2019, pp. 21–22, 37.

- ^ Broome, Richard (2019). Aboriginal Australians. Sydney: Allen and Unwin. p. 12. ISBN 9781760528218.

- ^ Wyrwoll, Karl-Heinz (11 January 2012). "How Aboriginal burning changed Australia's climate". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 15 July 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Clark, Anna (31 August 2023). "Friday essay: traps, rites and kurrajong twine – the incredible ingenuity of Indigenous fishing knowledge". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 11 February 2024. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Flood 2019, pp. 239–40.

- ^ Williams, Elizabeth (2015). "Complex hunter-gatherers: a view from Australia". Antiquity. 61 (232). Cambridge University Press: 310–321. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00052182. S2CID 162146349.

- ^ Flood 2019, pp. 25–27, 146.

- ^ Gammage, Bill (October 2011). The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Allen & Unwin. pp. 281–304.

- ^ Sutton, Peter; Walshe, Keryn (2021). Farmers or Hunter-Gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing. ISBN 9780522877854.

- ^ Veth & O'Connor 2013, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Flood 2019, pp. 198–99.

- ^ Josh, Nicholas; Wahlquist, Calla; Ball, Andy; Evershed, Nick (7 May 2021). "Who owns Australia". The Guardian Australia. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ Broome, Richard (2019). p. 353-54

- ^ Productivity Commission (January 2024). Review of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap: Study report Volume I. Canberra: Australian Government. p. 3.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search