Back تاريخ طاقة الرياح Arabic Geschichte der Windenergienutzung German Tuulivoiman historia Finnish Povijest vjetroelektrana Croatian Vindkraftens historia Swedish

Wind power has been used as long as humans have put sails into the wind. Wind-powered machines used to grind grain and pump water — the windmill and wind pump — were developed in what is now Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan by the 9th century.[1][2] Wind power was widely available and not confined to the banks of fast-flowing streams, or later, requiring sources of fuel. Wind-powered pumps drained the polders of the Netherlands, and in arid regions such as the American midwest or the Australian outback, wind pumps provided water for livestock and steam engines.

With the development of electric power, wind power found new applications in lighting buildings remote from centrally generated power. Throughout the 20th century, parallel paths developed small wind plants suitable for farms or residences and larger utility-scale wind generators that could be connected to electricity grids for remote use of power. Wind-powered generators operate in sizes ranging between tiny plants for battery charging at isolated residences up to near-gigawatt sized offshore wind farms that provide electricity to national electrical networks.

The first electricity-generating wind turbine was installed by the Austrian Josef Friedländer at the Vienna International Electrical Exhibition in 1883,[3][4][5] followed by wind generators, e.g., in Scotland in July 1887 by Prof James Blyth of Anderson's College, Glasgow (the precursor of Strathclyde University).[6] Blyth's 10 metres (33 ft) high cloth-sailed wind turbine was installed in the garden of his holiday cottage at Marykirk in Kincardineshire, and was used to charge accumulators developed by the Frenchman Camille Alphonse Faure to power the lighting in the cottage,[6] thus making it the first house in the world to have its electric power supplied by wind power.[7] Blyth offered the surplus electric power to the people of Marykirk for lighting the main street; however, they turned down the offer, as they thought electric power was "the work of the devil."[6] Although he later built a wind turbine to supply emergency power to the local Lunatic Asylum, Infirmary, and Dispensary of Montrose, the invention never really caught on, as the technology was not considered to be economically viable.[6]

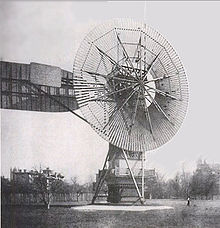

Across the Atlantic, in Cleveland, Ohio, a larger and heavily engineered machine was designed and constructed in the winter of 1887–1888 by Charles F. Brush.[8] This was built by his engineering company at his home and operated from 1886 until 1900.[9] The Brush wind turbine had a rotor 17 metres (56 ft) in diameter and was mounted on an 18 metres (59 ft) tower. Although large by today's standards, the machine was only rated at 12 kW. The connected dynamo was used either to charge a bank of batteries or to operate up to 100 incandescent light bulbs, three arc lamps, and various motors in Brush's laboratory.[10] With the development of electric power, wind power found new applications in lighting buildings remote from centrally generated power. Throughout the 20th century, parallel paths developed small wind stations suitable for farms or residences. From 1932, many isolated properties in Australia ran their lighting and electric fans from batteries, charged by a "Freelite" wind-driven generator, producing 100 watts of electrical power from as little wind speed as 10 miles per hour (16 km/h).[11]

The 1973 oil crisis triggered the investigation in Denmark and the United States that led to larger utility-scale wind generators that could be connected to electric power grids for remote use of power. By 2008, the U.S. installed capacity had reached 25.4 gigawatts, and by 2012, the installed capacity was 60 gigawatts.[12] Today, wind-powered generators operate in every size range, between tiny stations for battery charging at isolated residences up to gigawatt-sized offshore wind farms that provide electric power to national electrical networks. By the early 2020s, wind produced 3% of global total primary energy[13] and generated 7% of electricity.[14]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Islamic Technology p. 54was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Lucas, Adam (2006), Wind, Water, Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology, Brill Publishers, p. 65, ISBN 90-04-14649-0

- ^ "Austrian was First with Wind-Electric Turbine Not Byth or de Goyon". WIND WORKS. 25 July 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ Windkraft, I. G. (2 August 2023). "Sensation: Österreicher baute bereits vor 140 Jahren das erste Windrad". www.igwindkraft.at (in German). Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ "Die internationale elektrische Ausstellung Wien 1883 : unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Organisation, sowie der baulichen und maschinellen Anlagen / von E. R. Leonhardt". www.e-rara.ch. 1884. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

Pricewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Shackleton, Jonathan. "World First for Scotland Gives Engineering Student a History Lesson". The Robert Gordon University. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ Anon. Mr. Brush's Windmill Dynamo Archived 7 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Scientific American, Vol. 63 No. 25, 20 December 1890, p. 54.

- ^ A Wind Energy Pioneer: Charles F. Brush Archived 8 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Danish Wind Industry Association. Accessed 2 May 2007.

- ^ "History of Wind Energy" in Cutler J. Cleveland (ed.) Encyclopedia of Energy. Vol. 6, Elsevier, ISBN 978-1-60119-433-6, 2007, pp. 421–22

- ^ ""Freelite"". The Longreach Leader. Vol. 11, no. 561. Queensland, Australia. 16 December 1933. p. 5. Retrieved 26 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "History of U.S. Wind Energy". Energy.gov. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max. "Energy Production and Consumption". Our World in Data. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max. "Electricity Mix". Our World in Data. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search