Back བཀའ་ཤག་བཙུགས་ཚུལ། Tibetan Kashag Spanish Kashag French कशाग Hindi Kashag ID Kashag Dutch Kaszag Polish Kashag Portuguese Кашаг Russian 噶廈 Chinese

The Kashag (Tibetan: བཀའ་ཤག ་, Wylie: bkaʼ-shag, ZYPY: Gaxag, Lhasa dialect: [ˈkáɕaʔ]; Chinese: 噶廈; pinyin: Gáxià) was the governing council of Tibet during the rule of the Qing dynasty and post-Qing period until the 1950s. It was created in 1721,[1] and set by Qianlong Emperor in 1751 for the Ganden Phodrang in the 13-Article Ordinance for the More Effective Governing of Tibet. In that year the Tibetan government was reorganized after the riots in Lhasa of the previous year. The civil administration was represented by the Council (Kashag) after the post of Desi (or Regent; see: dual system of government) was abolished by the Qing imperial court. The Qing imperial court wanted the 7th Dalai Lama to hold both religious and administrative rule, while strengthening the position of the High Commissioners.[2][3][4][5]

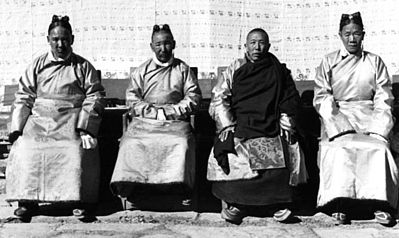

As specified by the 13-Article Ordinance for the More Effective Governing of Tibet, Kashag was composed of three temporal officials and one monk official. Each of them held the title of Kalön (Tibetan: བཀའ་བློན་, Wylie: bkaʼ-blon, Lhasa dialect: [kálø ̃]; Chinese: 噶倫; pinyin: gálún), sought appointment from the Qing imperial court, and the Qing imperial court issued certificates of appointment.[2]

The function of the council was to decide government affairs collectively,[2] and present opinions to the office of the first minister. The first minister then presented these opinions to the Dalai Lama and, during the Qing Dynasty the Amban, for a final decision. The privilege of presenting recommendations for appointing executive officials, governors and district commissioners gave the Council much power.

In August 1929, the Supreme Court of the Central Government stated that before the publication of new laws, laws in history regarding Tibet, regarding reincarnation of rinpoches, lamas were applicable.[6]

On 28 March 1959, Zhou Enlai, the premier of the People's Republic of China (PRC), formally announced the dissolution of the Kashag.[7][8]

- ^ Dawa Norbu, China's Tibet Policy

- ^ a b c Jiawei Wang; Gyaincain Nyima; Jiawei Wang (1997). The Historical Status of China's Tibet. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-7-80113-304-5.

- ^ Seventh Dalai Lama Kelsang Gyatso Archived 2010-07-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Dalai Lamas of Tibet, p. 101. Thubten Samphel and Tendar. Roli & Janssen, New Delhi. (2004). ISBN 81-7436-085-9.

- ^ Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa, Tibet, a Political History (New Haven: Yale, 1967), 150.

- ^ "【边疆时空】喜饶尼玛 李双|国民政府管理藏传佛教活佛措施评析_蒙藏". www.sohu.com. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~hpcws/jcws.2006.8.3.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Jian, Chen (2006). "The Tibetan Rebellion of 1959 and China's Changing Relations with India and the Soviet Union". Journal of Cold War Studies. 8 (3): 54–101. doi:10.1162/jcws.2006.8.3.54. ISSN 1520-3972. JSTOR 26925942. S2CID 57566391.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search