Back Tempelridders Afrikaans Orden d'o Temple AN Cnihtas þæm Temple ANG فرسان الهيكل Arabic فرسان المعبد ARZ Caballeros templarios AST Tampliyerlər Azerbaijani Tamplėirē BAT-SMG Тампліеры Byelorussian Тампліеры BE-X-OLD

| Part of a series on the |

| Knights Templar |

|---|

|

|

Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon |

| Overview |

| Councils |

| Papal bulls |

|

| Locations |

| Successors |

| Cultural references |

| See also |

|

|

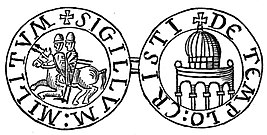

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, mainly known as the Knights Templar, was a French military order of the Catholic faith, and one of the wealthiest and most popular military orders in Western Christianity. They were founded c. 1119, headquartered on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, and existed for nearly two centuries during the Middle Ages.

Officially endorsed by the Roman Catholic Church by such decrees as the papal bull Omne datum optimum of Pope Innocent II, the Templars became a favoured charity throughout Christendom and grew rapidly in membership and power. The Templar knights, in their distinctive white mantles with a red cross, were among the most skilled fighting units of the Crusades. They were prominent in Christian finance; non-combatant members of the order, who made up as much as 90% of their members,[2][3] managed a large economic infrastructure throughout Christendom.[4] They developed innovative financial techniques that were an early form of banking,[5][6] building a network of nearly 1,000 commanderies and fortifications across Europe and the Holy Land, and arguably forming one of the world's earliest multinational corporations.[7]

The Templars were closely tied to the Crusades. As they became unable to secure their holdings in the Holy Land, support for the order faded.[8] Rumours about the Templars' secret initiation ceremony created distrust, and King Philip IV of France, while being deeply in debt to the order, used this distrust to take advantage of the situation. In 1307, he pressured Pope Clement V to have many of the order's members in France arrested, tortured into giving false confessions, and then burned at the stake.[9] Under further pressure, Pope Clement V disbanded the order in 1312.[10] The abrupt disappearance of a major part of the medieval European infrastructure gave rise to speculation and legends, which have kept the "Templar" name alive to this day.

- ^ Archer, Thomas Andrew; Kingsford, Charles Lethbridge (1894). The Crusades: The Story of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. T. Fisher Unwin. p. 176.; Burgtorf, Jochen (2008). The central convent of Hospitallers and Templars : history, organization, and personnel (1099/1120–1310). Leiden: Brill. pp. 545–46. ISBN 978-90-04-16660-8.

- ^ a b Burman 1990, p. 45.

- ^ a b Barber 1992, pp. 314–26

By Molay's time the Grand Master was presiding over at least 970 houses, including commanderies and castles in the east and west, serviced by a membership which is unlikely to have been less than 7,000, excluding employees and dependents, who must have been seven or eight times that number.

- ^ Selwood, Dominic (2002). Knights of the Cloister. Templars and Hospitallers in Central-Southern Occitania 1100–1300. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-828-0.

- ^ Martin 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Nicholson 2001, p. 4.

- ^ Barber 1994.

- ^ Miller, Duane (2017). 'Knights Templar' in War and Religion, Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, California: ABC–CLIO. pp. 462–64. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ Barber 1993.

- ^ Barber, Malcolm (1995). The new knighthood : a history of the Order of the Temple (Canto ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. xxi–xxii. ISBN 978-0-521-55872-3.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search