Back الترجمات اللاتينية في القرن الثاني عشر Arabic Traduccions llatines del segle XII Catalan Lateinische Übersetzungen im Hochmittelalter German Traducciones latinas del siglo XII Spanish Käännökset latinaan keskiajalla Finnish Traductions latines du XIIe siècle French Traductiones latin del seculo XII Interlingua Traduzioni nell'Occidente latino durante il XII secolo Italian Traduis latina de la sentenio 12 LFN Латинские переводы XII века Russian

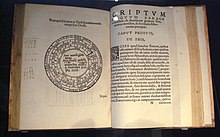

Latin translations of the 12th century were spurred by a major search by European scholars for new learning unavailable in western Europe at the time; their search led them to areas of southern Europe, particularly in central Spain and Sicily, which recently had come under Christian rule following their reconquest in the late 11th century. These areas had been under Muslim rule for a considerable time, and still had substantial Arabic-speaking populations to support their search. The combination of this accumulated knowledge and the substantial numbers of Arabic-speaking scholars there made these areas intellectually attractive, as well as culturally and politically accessible to Latin scholars.[2] A typical story is that of Gerard of Cremona (c. 1114–87), who is said to have made his way to Toledo, well after its reconquest by Christians in 1085, because he:

arrived at a knowledge of each part of [philosophy] according to the study of the Latins, nevertheless, because of his love for the Almagest, which he did not find at all amongst the Latins, he made his way to Toledo, where seeing an abundance of books in Arabic on every subject, and pitying the poverty he had experienced among the Latins concerning these subjects, out of his desire to translate he thoroughly learnt the Arabic language.[3]

Many Christian theologians were highly suspicious of ancient philosophies and especially of the attempts to synthesize them with Christian doctrines. St. Jerome, for example, was hostile to Aristotle, and St. Augustine had little interest in exploring philosophy, only applying logic to theology.[4] For centuries, ancient Greek ideas in Western Europe were all but non-existent. Only a few monasteries had Greek works, and even fewer of them copied these works.[5]

There was a brief period of revival, when the Anglo-Saxon monk Alcuin and others reintroduced some Greek ideas during the Carolingian Renaissance.[6] After Charlemagne's death, however, intellectual life again fell into decline. Excepting a few persons promoting Boethius, such as Gerbert of Aurillac, philosophical thought was developed little in Europe for about two centuries.[7] By the 12th century, however, scholastic thought was beginning to develop, leading to the rise of universities throughout Europe. These universities gathered what little Greek thought had been preserved over the centuries, including Boethius' commentaries on Aristotle. They also served as places of discussion for new ideas coming from new translations from Arabic throughout Europe.[8]

By the 12th century, Toledo, in Spain, had fallen from Arab hands in 1085, Sicily in 1091, and Jerusalem in 1099.[9] The small population of the Crusader Kingdoms contributed very little to the translation efforts, though Sicily, still largely Greek-speaking, was more productive. Sicilians, however, were less influenced by Arabic than the other regions and instead are noted more for their translations directly from Greek to Latin. Spain, on the other hand, was an ideal place for translation from Arabic to Latin because of a combination of rich Latin and Arab cultures living side by side.[10]

Unlike the interest in the literature and history of classical antiquity during the Renaissance, 12th century translators sought new scientific, philosophical and, to a lesser extent, religious texts. The latter concern was reflected in a renewed interest in translations of the Greek Church Fathers into Latin, a concern with translating Jewish teachings from Hebrew, and an interest in the Qur'an and other Islamic religious texts.[11] In addition, some Arabic literature was also translated into Latin.[12]

- ^ Suter & Samsó 1960–2007.

- ^ See, e.g., Sarton 1952, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Burnett 2001, p. 255.

- ^ Laughlin 1995, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Laughlin 1995, p. 139.

- ^ Laughlin 1995, p. 141.

- ^ Laughlin 1995, pp. 143–146.

- ^ Laughlin 1995, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Watt 1972, pp. 59–60; Lindberg 1978, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Lindberg 1978, pp. 58–59.

- ^ D'Alverny 1982, pp. 426–433.

- ^ Irwin 2003, p. 93.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search