Back حركة الأول من مارس Arabic Moviment Primer de Març Catalan Bewegung des ersten März German Κίνημα της 1ης Μαρτίου Greek Movimiento Primero de Marzo Spanish Martxoaren 1eko mugimendua Basque جنبش اول مارس Persian Maaliskuun 1. päivän liike Finnish Mouvement du 1er mars French Pergerakan 1 Maret ID

A request that this article title be changed to March First Movement is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

| March 1st Movement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Korean independence movement | |||

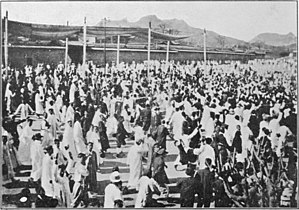

A march during one of the protests in Seoul (1919) | |||

| Date | March 1, 1919 – months afterwards | ||

| Location |

| ||

| Caused by | Ideals of self-determination, discontent with colonial rule, and theories that former Emperor Gojong had been poisoned by Japan | ||

| Goals |

| ||

| Methods | Nonviolent resistance | ||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Concessions | Colonial government granted limited cultural freedoms as part of its cultural rule policies | ||

| Parties | |||

| Number | |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | Around 798[1] to 7,509[2][3] | ||

| Arrested | 46,948 (1920 Korean estimate)[2][3] | ||

The March 1st Movement[a] was a series of protests against Japanese colonial rule that were held throughout Korea and internationally by the Korean diaspora beginning on March 1, 1919. Protests continued until the end of the year, although in significantly smaller numbers after May.[1] In South Korea, the movement is remembered as a landmark event of not only the Korean independence movement, but of all of Korean history.

The protests began in Seoul, with public readings of the Korean Declaration of Independence in the restaurant Taehwagwan and in Tapgol Park. The movement grew and spread rapidly. Statistics on the protest are uncertain; there were around 1,500 to 1,800 protests with a total of around 0.8 to 2 million participants. Despite the peaceful nature of the protests, they were frequently violently suppressed. One Korean estimate in 1920 claimed 7,509 deaths and 46,948 arrests. Japanese authorities reported much lower numbers, although there were instances where authorities were observed destroying evidence, such as during the Jeamni massacre, where Japanese soldiers burnt down a church to destroy the bodies of around 20 to 30 Korean civilians they had lured into the church before killing.[7] Japanese authorities then conducted a global disinformation campaign on the protests.[8] They promoted a wide range of narratives, including outright denial of any protests occurring,[9] portraying them as violent Bolshevik uprisings,[10][11] and claiming that Koreans were uncivilized, incapable of self-government, and needed the benevolent rule of Japan.[12][13][14] These narratives were publicly challenged by sympathetic foreigners and by the Korean diaspora.

The movement did not result in Korea's prompt liberation, but had a number of significant effects. It invigorated the Korean independence movement and resulted in the creation of the Korean Provisional Government. It also caused some damage to Japan's international reputation and caused the Japanese colonial government to grant some limited cultural freedoms to Koreans under a series of policies that have since been dubbed "cultural rule". Furthermore, the movement went on to inspire other movements abroad, including the Chinese May Fourth Movement and Indian satyagraha protests.[15]

The anniversary of the movement's start has been celebrated since, although this was largely done in secret in Korea until its liberation in 1945. In South Korea, it is a national holiday. The North Korean government initially celebrated it as a national holiday, but eventually demoted it and now does not evaluate the movement's significance similarly. It now promotes writings about the event that seek to emphasize the role of the ruling Kim family in the protests.[16][17]

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Database Incidentswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

EncyKorea Movementwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Kwon 2018, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Hart 2000, p. 151.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Japan Focuswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ 윤, 호창 (2019-02-19). "3.1혁명 100년, 이젠 복지국가 혁명이다". Pressian (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ 김, 진봉, "수원 제암리 참변 (水原 堤岩里 慘變)", Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean), Academy of Korean Studies, retrieved 2024-04-30

- ^ Palmer 2020, pp. 208–209.

- ^ 김, 상훈 (2019-02-14). "[외신속 3·1 운동] ① 그 날 그 함성…통제·조작의 '프레임' 뚫고 세계로". Yonhap News Agency (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Palmer 2020, p. 204.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

YNA 2019 9was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Palmer 2020, p. 210.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

YNA 2019 1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

YNA 2019 6was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Shin, Yong-ha (February 27, 2009). "Why Did Mao, Nehru and Tagore Applaud the March First Movement?". The Chosun Ilbo. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2009-06-27 – via Korea Focus.

- ^ Kim, Hyeon-gyeong (1 March 1997). "In North Korea, March 1st is distortedly taught as being caused by the Kim Il-sung family". MBC News. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Hart 2000, pp. 153–154.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search