Back باندز Arabic PANDAS sindromu Azerbaijani PANDAS German PANDAS Spanish پانداس Persian PANDAS French PANDAS Italian Autoimmunologiczny pediatryczny zespół zaburzeń neuropsychiatrycznych po infekcji Streptococcus Polish ПАНДАС Russian PANDAS Swedish

| PANDAS | |

|---|---|

| |

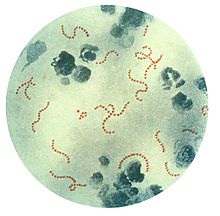

| Streptococcus pyogenes (stained red), a common group A streptococcal bacterium. PANDAS is speculated to be an autoimmune condition in which the body's own antibodies to streptococci attack the basal ganglion cells of the brain, by a concept known as molecular mimicry. | |

| Specialty | Neurology, Psychiatry |

Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) is a controversial[1][2] hypothetical diagnosis for a subset of children with rapid onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or tic disorders.[3] Symptoms are proposed to be caused by group A streptococcal (GAS), and more specifically, group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) infections.[3] OCD and tic disorders are hypothesized to arise in a subset of children as a result of a post-streptococcal autoimmune process.[4][5][6] The proposed link between infection and these disorders is that an autoimmune reaction to infection produces antibodies that interfere with basal ganglia function, causing symptom exacerbations, and this autoimmune response results in a broad range of neuropsychiatric symptoms.[3]

The PANDAS hypothesis, first described in 1998, was based on observations in clinical case studies by Susan Swedo et al at the US National Institute of Mental Health and in subsequent clinical trials where children appeared to have dramatic and sudden OCD exacerbations and tic disorders following infections.[7] Whether PANDAS was a distinct entity differing from other cases of tic disorders or OCD is debated.[1][8][9] As the PANDAS hypothesis was unconfirmed and unsupported by data, a new definition was proposed by Swedo and colleagues in 2012.[10] In addition to the 2012 broader pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS), two other categories have been proposed: childhood acute neuropsychiatric symptoms (CANS) and pediatric infection-triggered autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders (PITAND).[3] The CANS/PANS hypotheses include different possible mechanisms underlying acute-onset neuropsychiatric conditions, but do not exclude GAS infections as a cause in a subset of individuals.[5][6] PANDAS, PANS and CANS are the focus of clinical and laboratory research but remain unproven.[10][4][5][6]

There is no diagnostic test to accurately confirm PANDAS;[11] the diagnostic criteria are unevenly applied and the conditions may be overdiagnosed.[10] Treatment for children suspected of PANDAS is generally the same as the standard treatments for Tourette syndrome (TS) and OCD.[10] There is insufficient evidence or consensus to support treatment, although experimental treatments are sometimes used,[3] and adverse effects from unproven treatments are expected.[12] The media and the internet have contributed to an ongoing PANDAS controversy,[13][14] with reports of the difficulties of families who believe their children have PANDAS or PANS.[10] Attempts to influence public policy have been advanced by advocacy networks.[10]

- ^ a b Hsu CJ, Wong LC, Lee WT (January 2021). "Immunological dysfunction in Tourette syndrome and related disorders". Int J Mol Sci (Review). 22 (2): 853. doi:10.3390/ijms22020853. PMC 7839977. PMID 33467014.

- ^ Marazziti D, Palermo S, Arone A, et al. (2023). "Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, PANDAS, and Tourette Syndrome: Immuno-inflammatory Disorders". Neuroinflammation, Gut-Brain Axis and Immunity in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1411. pp. 275–300. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-7376-5_13. ISBN 978-981-19-7375-8. PMID 36949315.

- ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

Sigra2018was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Dale RC (December 2017). "Tics and Tourette: a clinical, pathophysiological and etiological review". Curr Opin Pediatr (Review). 29 (6): 665–673. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000546. PMID 28915150. S2CID 13654194.

- ^ a b c Marazziti D, Mucci F, Fontenelle LF (July 2018). "Immune system and obsessive-compulsive disorder". Psychoneuroendocrinology (Review). 93: 39–44. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.04.013. PMID 29689421. S2CID 13681480.

- ^ a b c Zibordi F, Zorzi G, Carecchio M, Nardocci N (March 2018). "CANS: Childhood acute neuropsychiatric syndromes". Eur J Paediatr Neurol (Review). 22 (2): 316–320. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.01.011. PMID 29398245.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

BPNAConwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Chiarello2017was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Robertson MM (February 2011). "Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: the complexities of phenotype and treatment" (PDF). Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 72 (2): 100–7. doi:10.12968/hmed.2011.72.2.100. PMID 21378617.

- ^ a b c d e f Wilbur C, Bitnun A, Kronenberg S, Laxer RM, Levy DM, Logan WJ, Shouldice M, Yeh EA (May 2019). "PANDAS/PANS in childhood: Controversies and evidence". Paediatr Child Health. 24 (2): 85–91. doi:10.1093/pch/pxy145. PMC 6462125. PMID 30996598.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Ueda2021was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Johnson2021was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Murphy2010was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Swerdlow2005was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search