Back غاية الحكيم Arabic পিকাট্রিক্স Bengali/Bangla Picatrix Catalan Picatrix German Picatrix Esperanto Libro de Picatrix Spanish غایة الحکیم Persian Picatrix Finnish Picatrix French Picatrix Croatian

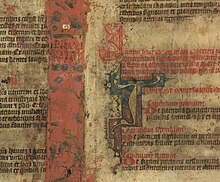

Picatrix is the Latin name used today for a 400-page book of magic and astrology originally written in Arabic under the title Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm (Arabic: غاية الحكيم), which most scholars assume was originally written in the middle of the 11th century,[1] though an argument for composition in the first half of the 10th century has been made.[2] The Arabic title translates as The Aim of the Sage or The Goal of The Wise.[3] The Arabic work was translated into Spanish and then into Latin during the 13th century, at which time it got the Latin title Picatrix. The book's title Picatrix is also sometimes used to refer to the book's author.

Picatrix is a composite work that synthesizes older works on magic and astrology. One of the most influential interpretations suggests it is to be regarded as a "handbook of talismanic magic".[4] Another researcher summarizes it as "the most thorough exposition of celestial magic in Arabic", indicating the sources for the work as "Arabic texts on Hermeticism, Sabianism, Ismailism, astrology, alchemy and magic produced in the Near East in the ninth and tenth centuries A.D."[5] Eugenio Garin declares, "In reality the Latin version of the Picatrix is as indispensable as the Corpus Hermeticum or the writings of Albumasar for understanding a conspicuous part of the production of the Renaissance, including the figurative arts."[6] It has significantly influenced West European esotericism from Marsilio Ficino in the 15th century, to Thomas Campanella in the 17th century. The manuscript in the British Library passed through several hands: Simon Forman, Richard Napier, Elias Ashmole and William Lilly.

According to the prologue of the Latin translation, Picatrix was translated into Spanish from the Arabic by order of Alphonso X of Castile at some time between 1256 and 1258.[7] The Latin version was produced sometime later, based on translation of the Spanish manuscripts. It has been attributed to Maslama ibn Ahmad al-Majriti (an Andalusian mathematician), but many have called this attribution into question. Consequently, the author is sometimes indicated as "Pseudo-Majriti".

The Spanish and Latin versions were the only ones known to Western scholars until Wilhelm Printz discovered an Arabic version in or around 1920.[8]

- ^ e.g Dozy, Holmyard, Samsó, and Pingree; David Pingree, 'Some of the Sources of the Ghāyat al-hakīm', in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 43, (1980), p. 2; Willy Hartner, 'Notes On Picatrix', in Isis, Vol. 56, No. 4, (Winter, 1965), pp. 438

- ^ Maribel Fierro, "Bāṭinism in Al-Andalus. Maslama b. Qāsim al-Qurṭubī (died 353/964), Author of the 'Rutbat al- Ḥakīm' and the 'Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm (Picatrix)'" in: Studia Islamica, No. 84, (1996), pp. 87–112.

- ^ However the Arabic translated as "goal" (ghaya, pl. ghayat) also suggests the sense of "utmost limit" or "boundary".

- ^ Frances Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Chicago, 1964; Frances Yates, The Art of Memory, Chicago, 1966

- ^ David Pingree, 'Some of the Sources of the Ghāyat al-hakīm', in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 43, (1980), pp. 1–15

- ^ Eugenio Garin, Astrology in the Renaissance: The Zodiac of Life, Routledge, 1983, p. 47

- ^ David Pingree, 'Between the Ghāya and Picatrix. I: The Spanish Version', in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 44, (1981), p. 27

- ^ Willy Hartner, 'Notes On Picatrix', in Isis, Vol. 56, No. 4, (Winter, 1965), pp. 438–440; the Arabic text was published for the first time by the Warburg Library in 1927.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search