Back بيم فورتاين Arabic Pim Fortuyn Breton Pim Fortuyn Catalan پیم فۆرتاین CKB Pim Fortuyn Czech Pim Fortuyn Danish Pim Fortuyn German Pim Fortuyn Esperanto Pim Fortuyn Spanish Pim Fortuyn Estonian

Pim Fortuyn | |

|---|---|

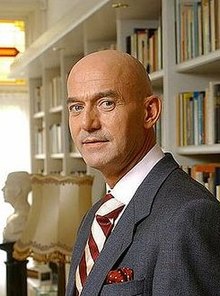

Fortuyn on 4 May 2002, two days before his assassination | |

| Born | Wilhelmus Simon Petrus Fortuijn 19 February 1948 Velsen, Netherlands |

| Died | 6 May 2002 (aged 54) Hilversum, Netherlands |

| Cause of death | Assassination (gunshot wounds) |

| Resting place | San Giorgio della Richinvelda, Italy |

| Other names | Pim Fortuijn |

| Alma mater | VU Amsterdam (Bachelor of Social Science, Master of Social Science) University of Groningen (PhD) |

| Occupation(s) | Politician · civil servant · Sociologist Corporate director · Political consultant · Political pundit · Author · Columnist · Publisher · Teacher · professor |

| Political party | Labour Party (1974–1989) People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (mid 1990s) Livable Netherlands (2001–2002) Livable Rotterdam (2001–2002) Pim Fortuyn List (2002) |

| Signature | |

| |

Wilhelmus Simon Petrus Fortuijn, known as Pim Fortuyn (Dutch: [ˈpɪɱ fɔrˈtœyn] ; 19 February 1948 – 6 May 2002), was a Dutch politician, author, civil servant, businessman, sociologist and academic who founded the party Pim Fortuyn List (Lijst Pim Fortuyn or LPF) in 2002.[1]

Fortuyn worked as a professor at the Erasmus University of Rotterdam before branching into a business career and was an advisor to the Dutch government on social infrastructure. He then became prominent in the Netherlands as a press columnist, writer and media commentator.

Initially a Marxist who was sympathetic to the Communist Party of the Netherlands, and later a member of the Dutch Labour Party in the 1970s, Fortuyn's beliefs began to shift to the right in the 1990s, especially related to the immigration policies of the Netherlands. Fortuyn criticised multiculturalism, immigration and Islam in the Netherlands. He called Islam "a backward culture", and was quoted as saying that if it were legally possible, he would close the borders for Muslim immigrants.[2] Fortuyn also supported tougher measures against crime and opposed state bureaucracy,[3] wanting to reduce the Dutch financial contribution to the European Union.[4] He was labelled a far-right populist by his opponents and in the media, but he fiercely rejected this label.[5] Fortuyn was openly gay and a supporter of gay rights.[6]

Fortuyn explicitly distanced himself from "far-right" politicians such as the Belgian Filip Dewinter, Austrian Jörg Haider, or Frenchman Jean-Marie Le Pen whenever compared to them. While he compared his own politics to centre-right politicians such as Silvio Berlusconi of Italy and Edmund Stoiber of Germany, he also admired former Dutch Prime Minister Joop den Uyl, a social democrat, and Democratic U.S. president John F. Kennedy. Fortuyn also criticised the polder model and the policies of the outgoing government of Wim Kok and repeatedly described himself and LPF's ideology as pragmatic and not populistic.[7] In March 2002, his newly created LPF became the largest party in Fortuyn's hometown Rotterdam during the Dutch municipal elections held that year.[8]

Fortuyn was assassinated during the 2002 Dutch national election campaign[9][10][11] by Volkert van der Graaf, a left-wing environmentalist and animal rights activist.[12] In court at his trial, van der Graaf said he murdered Fortuyn to stop him from exploiting Muslims as "scapegoats" and targeting "the weak members of society" in seeking political power.[13][14][15] The LPF went on to poll in second place during the election but went into decline soon after.

- ^ Margry, Peter Jan: The Murder of Pim Fortuyn and C's ollective Emotions. Hype, Hysteria, and Holiness in the Netherlands? published in the Dutch magazine Etnofoor: Antropologisch tijdschrift nr. 16 pages 106–131, 2003,English version available online Archived 29 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Volkskrant newspaper interview (summary)" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 12 February 2002. Retrieved 12 February 2002.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Oliver, Mark (7 May 2002). "The shooting of Pym Fortuyn". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ^ Osborn, Andrew (14 April 2002). "Dutch fall for gay Mr Right". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ "Cf. this BBC interview". 4 May 2002. Archived from the original on 20 October 2002. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (15 May 2002). "Queering the pitch". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ "Interview with Belgium news agency". YouTube. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ The Guardian (7 May 2002). "Dutch election to go ahead". TheGuardian.com. London. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (7 May 2002). "Rightist Candidate in Netherlands Is Slain, and the Nation Is Stunned". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ James, Barry (7 May 2002). "Assailant shoots gay who railed against Muslim immigrants: Rightist in Dutch election is murdered". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (8 May 2002). "Elections to Proceed in the Netherlands, Despite Killing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ The Daily Telegraph (29 March 2003). "Killer tells court Fortuyn was dangerous". Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ Fortuyn killed 'to protect Muslims' Archived 28 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Telegraph, 28 March 2003:

- [van der Graaf] said his goal was to stop Mr. Fortuyn exploiting Muslims as "scapegoats" and targeting "the weak parts of society to score points" to try to gain political power.

- ^ Fortuyn killer 'acted for Muslims' Archived 10 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, CNN, 27 March 2003:

- Van der Graaf, 33, said during his first court appearance in Amsterdam on Thursday that Fortuyn was using "the weakest parts of society to score points" and gain political power.

- ^ "Jihad Vegan". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Dr Janet Parker 20 June 2005, New Criminologist.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search