Back Tweede Persiese oorlog Afrikaans غزو الفرس الثاني لليونان Arabic Yunan-İran müharibəsi (e.ə. 480-e.ə. 479) Azerbaijani ایکینجی ایران و یونان ساواشی AZB Втора персийска инвазия в Гърция Bulgarian Segona Guerra Mèdica Catalan Β΄ Περσικός Πόλεμος Greek Segunda guerra médica Spanish دومین تهاجم ایرانیان به یونان Persian Seconde guerre médique French

| Second Persian invasion of Greece | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greco-Persian Wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Athens Sparta Other Greek city states | Achaemenid Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Leonidas I † Themistocles Pausanias Leotychidas II Eurybiades Aristides |

'Xerxes I Artemisia I of Caria Mardonius † Hydarnes | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Land forces: 10,000 Spartans 9,000 Athenians 5,000 Corinthians 2,000 Thespians 1,000 Phocians 30,000 Greeks from other city-states, including Arcadia, Aegina, Eretria, and Plataea Sea forces: 400 triremes 6,000 marines 68,000 oarsmen Total: 125,000 men 400 ships |

Land forces: 15,000–25,000[1] Sea forces: 600[3]–1,200 ships (modern estimates)

(ancient sources) | ||||||

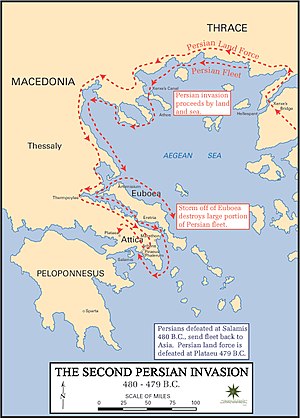

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion of Greece (492–490 BC) at the Battle of Marathon, which ended Darius I's attempts to subjugate Greece. After Darius's death, his son Xerxes spent several years planning for the second invasion, mustering an enormous army and navy. The Athenians and Spartans led the Greek resistance. About a tenth of the Greek city-states joined the 'Allied' effort; most remained neutral or submitted to Xerxes.

The invasion began in spring 480 BC, when the Persian army crossed the Hellespont and marched through Thrace and Macedon to Thessaly. The Persian advance was blocked at the pass of Thermopylae by a small Allied force under King Leonidas I of Sparta; simultaneously, the Persian fleet was blocked by an Allied fleet at the straits of Artemisium. At the famous Battle of Thermopylae, the Allied army held back the Persian army for three days, before they were outflanked by a mountain path and the Allied rearguard was trapped and annihilated. The Allied fleet had also withstood two days of Persian attacks at the Battle of Artemisium, but when news reached them of the disaster at Thermopylae, they withdrew to Salamis.

After Thermopylae, all of Euboea, Phocis, Boeotia and Attica fell to the Persian army, which captured and burnt Athens. However, a larger Allied army fortified the narrow Isthmus of Corinth, protecting the Peloponnesus from Persian conquest. Both sides thus sought a naval victory that might decisively alter the course of the war. The Athenian general Themistocles succeeded in luring the Persian navy into the narrow Straits of Salamis, where the huge number of Persian ships became disorganised, and were soundly beaten by the Allied fleet. The Allied victory at Salamis prevented a quick conclusion to the invasion, and fearing becoming trapped in Europe, Xerxes retreated to Asia leaving his general Mardonius to finish the conquest with the elite of the army.

The following spring, the Allies assembled the largest ever hoplite army and marched north from the Isthmus to confront Mardonius. At the ensuing Battle of Plataea, the Greek infantry again proved its superiority, inflicting a severe defeat on the Persians and killing Mardonius in the process. On the same day, across the Aegean Sea an Allied navy destroyed the remnants of the Persian navy at the Battle of Mycale. With this double defeat, the invasion was ended, and Persian power in the Aegean severely dented. The Greeks would now move to the offensive, eventually expelling the Persians from Europe, the Aegean Islands and Ionia before the war finally came to an end in 449 BC with the Peace of Callias.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search