This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2014) |

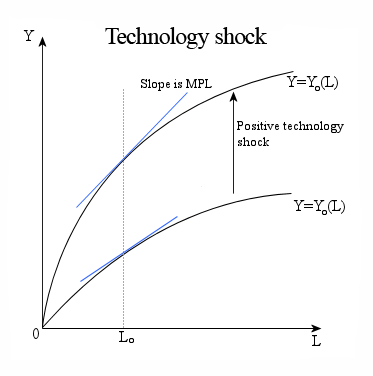

The technology shock increases the output given the same level of, in this case, labor. The marginal product of labor is higher after the positive technology shock, this can be seen in the MPL (blue) line being steeper.

Technology shocks are sudden changes in technology that significantly affect economic, social, political or other outcomes.[1] In economics, the term technology shock usually refers to events in a macroeconomic model, that change the production function. Usually this is modeled with an aggregate production function that has a scaling factor.

Normally reference is made to positive (i.e., productivity enhancing) technological changes, though technology shocks can also be contractionary.[2] The term “shock” connotes the fact that technological progress is not always gradual – there can be large-scale discontinuous changes that significantly alter production methods and outputs in an industry, or in the economy as a whole. Such a technology shock can occur in many different ways.[3] For example, it may be the result of advances in science that enable new trajectories of innovation, or may result when an existing technological alternative improves to a point that it overtakes the dominant design, or is transplanted to a new domain. It can also occur as the result of a shock in another system, such as when a change in input prices dramatically changes the price/performance relationship for a technology,[4] or when a change in the regulatory environment significantly alters the technologies permitted (or demanded) in the market. Numerous studies have shown that technology shocks can have a significant effect on investment, economic growth, labor productivity, collaboration patterns, and innovation.[5]

- ^ Schilling, M. A. (2015). "Technology Shocks, Technological Collaboration, and Innovation Outcomes". Organization Science. 26 (3): 668–686. doi:10.1287/orsc.2015.0970.

- ^ Basu, S., Fernald, J.G., Kimball, M.S. (2006) "Are technology improvements contractionary?" American Economic Review 96:1418-1448.

- ^ Schilling, M. A. (2015). "Technology Shocks, Technological Collaboration, and Innovation Outcomes". Organization Science 26 (3): 668–686. doi:10.1287/orsc.2015.0970.

- ^ Ehrnberg, E. (1995) "On the definition and measurement of technological discontinuities." Technovation Volume 15, Issue 7, September 1995, pp. 437-452.

- ^ Alexopoulos, M. (2011) "What Happens Following a Technology Shock?" American Economic Review, 101 (4): 1144-79. DOI: 10.1257/aer.101.4.1144; Christiano, L.J. Eichenbaum, M. and Vigfusson, R.J. (2003) What Happens after a Technology Shock? NBER Working Paper No. w9819. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=421780; Galí, J. (1999) "Technology, Employment, and the Business Cycle: Do Technology Shocks Explain Aggregate Fluctuations?" American Economic Review 89 (1): 249-271; Schilling, M. A. (2015). "Technology Shocks, Technological Collaboration, and Innovation Outcomes". Organization Science 26 (3): 668–686. doi:10.1287/orsc.2015.0970.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search