Back متلازمة الصدمة التسممية Arabic Síndrome de xoc tòxic Catalan Syndrom toxického šoku Czech Tamponsyge Danish Toxisches Schocksyndrom German Síndrome del choque tóxico Spanish Toksilise šoki sündroom Estonian Shock toxikoaren sindrome Basque سندرم شوک سمی Persian Toksinen sokkioireyhtymä Finnish

| Toxic shock syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

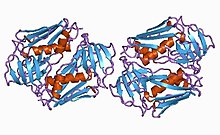

| Toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 protein from staphylococcus | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, rash, skin peeling, low blood pressure[1] |

| Complications | Shock, kidney failure[2] |

| Usual onset | Rapid[1] |

| Types | Staphylococcal (menstrual and nonmenstrual), streptococcal[1] |

| Causes | Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, others[1][3] |

| Risk factors | Very absorbent tampons, skin lesions in young children[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Septic shock, Kawasaki's disease, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, scarlet fever[4] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics, incision and drainage of any abscesses, intravenous immunoglobulin[1] |

| Prognosis | Risk of death: ~50% (streptococcal), ~5% (staphylococcal)[1] |

| Frequency | Staphylococcal: 0.3 to 0.5 cases per 100,000 population Streptococcal: 2 to 4 cases per 100,000 population |

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a condition caused by bacterial toxins.[1] Symptoms may include fever, rash, skin peeling, and low blood pressure.[1] There may also be symptoms related to the specific underlying infection such as mastitis, osteomyelitis, necrotising fasciitis, or pneumonia.[1]

TSS is typically caused by bacteria of the Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus type, though others may also be involved.[1][3] Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome is sometimes referred to as toxic-shock-like syndrome (TSLS).[1] The underlying mechanism involves the production of superantigens during an invasive streptococcus infection or a localized staphylococcus infection.[1] Risk factors for the staphylococcal type include the use of very absorbent tampons, skin lesions in young children characterized by fever, low blood pressure, rash, vomiting and/or diarrhea, and multiorgan failure.[1][5][6] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms.[1]

Treatment includes intravenous fluids, antibiotics, incision and drainage of any abscesses, and possibly intravenous immunoglobulin.[1][7] The need for rapid removal of infected tissue via surgery in those with a streptococcal cause, while commonly recommended, is poorly supported by the evidence.[1] Some recommend delaying surgical debridement.[1] The overall risk of death is about 50% in streptococcal disease, and 5% in staphylococcal disease.[1] Death may occur within 2 days.[1]

In the United States, the incidence of menstrual staphylococcal TSS declined sharply in the 1990s, while both menstrual and nonmenstrual cases have stabilized at about 0.3 to 0.5 cases per 100,000 population.[1] Streptococcal TSS (STSS) saw a significant rise in the mid-1980s and has since remained stable at 2 to 4 cases per 100,000 population.[1] In the developing world, the number of cases is usually on the higher extreme.[1] TSS was first described in 1927.[1] It got associated with very absorbent tampons that were removed from sale soon after.[1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Low DE (July 2013). "Toxic Shock Syndrome: Major Advances in Pathogenesis, But Not Treatment". Critical Care Clinics. 29 (3): 651–675. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2013.03.012. PMID 23830657 – via Elsevier.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Mayo20355384was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Gottlieb M, Long B, Koyfman A (June 2018). "The Evaluation and Management of Toxic Shock Syndrome in the Emergency Department: A Review of the Literature". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 54 (6): 807–814. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.12.048. PMID 29366615. S2CID 1812988.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Ferri9780323076999was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

cdcwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Khajuria A, Nadam HH, Gallagher M, Jones I, Atkins J (2020). "Pediatric Toxic Shock Syndrome After a 7% Burn: A Case Study and Systematic Literature Review". Ann. Plast. Surg. 84 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000001990. PMID 31192868. S2CID 189815024.

- ^ Wilkins AL, Steer AC, Smeesters PR, Curtis N (2017). "Toxic shock syndrome – the seven Rs of management and treatment". Journal of Infection. 74: S147–S152. doi:10.1016/S0163-4453(17)30206-2. PMID 28646955.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search